At the links below are special topics that arise from the study of various chapters and sections in Calvin’s Little Book:

John Calvin

Calvin’s Little Book, Chapter 2

Below are links to the respective week’s study in Chapter 2 of Calvin’s Little Book on the Christian Life.

Week #4: Chapter 2 “Self-Denial,” Sec.s 1-2

Week #5: Chapter 2 “Self-Denial,” Sec. 3

Week #6: Chapter 2 “Self-Denial,” Sec.s 5-6

Week #7: Chapter 2 “Self-Denial,” Sec.s 7-8

Week #8: Chapter 2 “Self-Denial,” Sec.s 9-10

Calvin’s Little Book, Week #15

We will use this week to review the territory we’ve covered in the 26 Sections of Calvin’s Chapters 1-3. Additionally we will connect the central point of Calvin’s “Little Book” with the key doctrinal concept of “sanctification.”

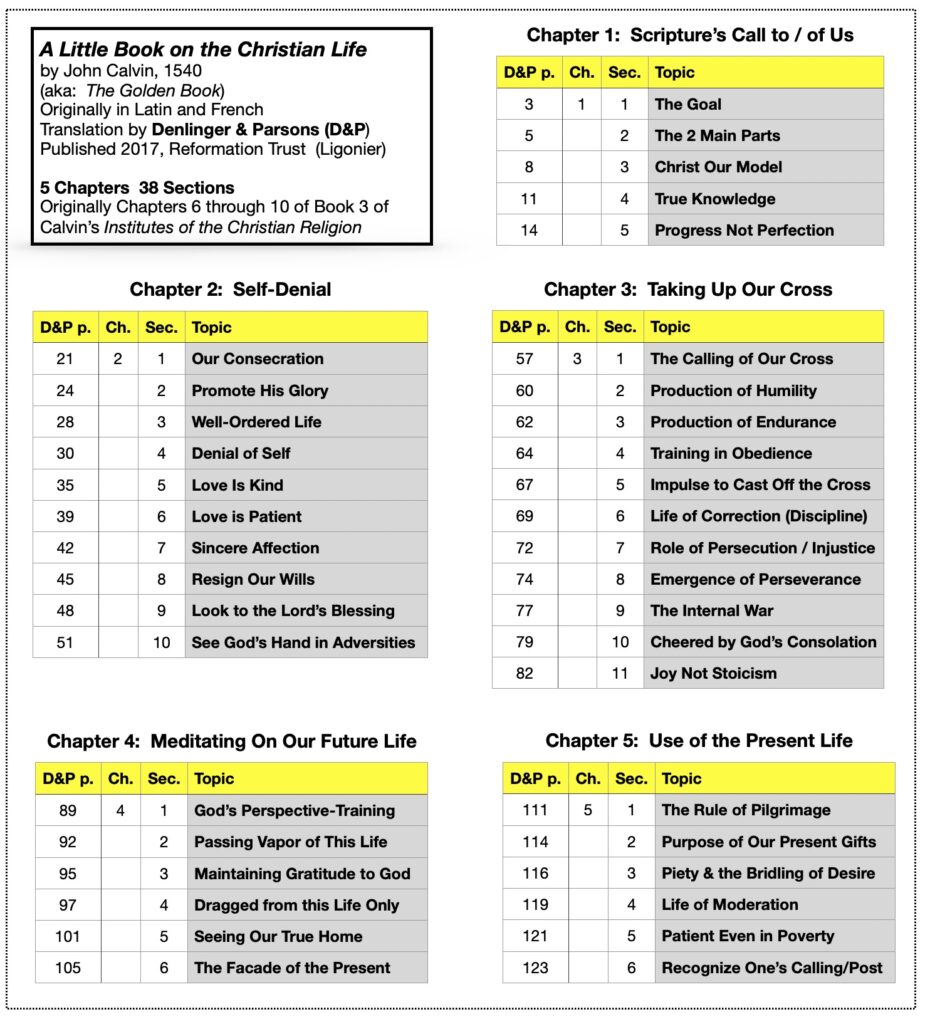

Maps of Calvin’s Little Book

The photograph below of modern Geneva Switzerland shows the medieval city where Calvin ministered for most of his adult life and where he wrote his Institutes of the Christian Religion from which the “Little Book” is taken.

The body of water at the top of the image is Lake Geneva, headed by its famous fountain. The red circle just below the fountain is the church named in honor of St Peter in Geneva, not to be confused with the Roman Catholic church of that same name that is part of the Vatican in Rome. This St Peter church is quite modest in size, and is much older (built in 1160-1260), and is sited on a very early, perhaps 3rd or not later than 6th Century, church foundation. It is where Calvin wrote and taught from 1536 to his death in 1563 with a brief ‘exile’ of several years (The Political Industry, TPI, of the time threw him out of the city for a time, but then invited him back).

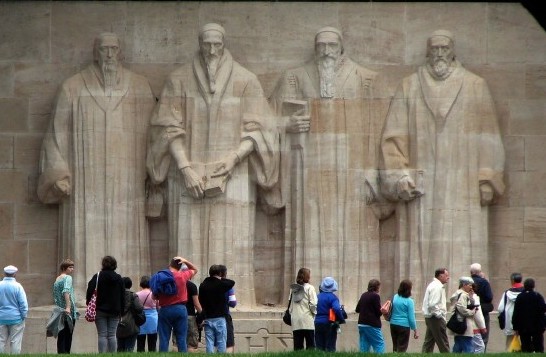

Not readily discernible in the picture is that the church building sits at the crest of a hill in what is known today as the old city. The red circle on the lower right is the Reformation Monument honoring–which Calvin would not have wanted–the four contemporaries who ministered there as key figures in the Reformation: Ferel (1489-1565), Calvin (1509-1563), Knox (1514-1572), and Beza (1519-1605). At the bottom of the photograph, below the Reformation Monument, is the University of Geneva, which was founded in 1559 by Calvin and Beza, more than 60 years before the founding of Harvard College, the oldest university in the United States. The University of Geneva then, as was Harvard at its founding, a theological seminary for the purpose of preparing scholars, teachers, preachers, and evangelists of the Bible.

The left-to-right order of the Reformation Wall Monument, shown in the photograph below, is Farel, Calvin, Beza, and Knox. John Knox later played a key role in establishing the reformation in Scotland. Theodore Beza was a great scholar of the original languages of the Bible; he published several important editions of the New Testament Koine Greek Bible. Beza owned a 5th century mss of Koine Greek and Latin, a so-called diglot, which he donated to Cambridge University in 1581, where it is preserved to this day; it can be viewed here: Beza’s Greek and Latin mss and translations were used by the translators of the KJV Bible.

Interesting side note: a Paris printer named Robert Estienne, aka “Stephanos,” moved his printing operations to Geneva (likely because of the persecution of the strong Roman Catholic presence in France), and printed Beza’s and other important works including the famed Geneva Bible of 1560. In the course of such printing, it was Estienne (Stephanos) who created all the 31,000 verses we now have that organizes our Bibles. Prior to that time, the Bible had only been divided into books and, beginning in ca. 1000 A.D., the 1189 chapters as we still have it today. The English translation of the Geneva Bible became the standard translation used by the Puritans in America, and by Shakespeare, John Milton, John Bunyan and many many others. It pre-dates and was largely the basis of the Authorized Version (AV), aka The King James Version (1611). The Geneva Bible was also the first “study Bible,” as it included many notes to aid the reader (and which notes were found objectionable to TPI and TRI of England which was a principal impetus for it to create a government-authorized Bible, the KJV).

A pdf of the 1560 Geneva Bible in its original now archaic English is available here:

A more accessible English text of the 1599 update of the 1560 Geneva Bible is available here: A special feature of such cite is the “Interlinear” option that shows multiple Koine (Greek) source texts and multiple English traditional translations (“traditional” in the sense such translations are based on the “texts receptus,” which means, approximately, the exclusive use of Koine mss as collected shortly after the completion of the KJV translation, and not the so-called “critical texts” developed from mss discoveries beginning in the late 18th Century).

Below is a pdf of such interlinear feature for the verse we will consider below on this page, Hebrews 1:3:

Sanctification

“Sanctification” is one of the pillars of Theology. It is connected with another foundational term–Justification–in an important way, that divides many followers of Christ.

The Reformation view, and the Bible’s clear teaching, is that Sanctification follows Justification, because Justification occurs only by God’s Sovereign raising the dead in sin. The opposing view, which has been in conflict with what has just been stated is that “justification” is the deserved / earned outcome of a life of continual “sanctification.” The line of separation between these opposing is somewhat blurred by many of the second view holding that “sanctification” can only occur because of the Work of God (The Holy Spirit), and so “the credit” is not really (all / solely) man’s. However, there remains an important line of separation because this second view is that man necessarily initiates sanctification by his first act of faith, perhaps because only his mind was “dead,” and not his will, or not all of his will, or perhaps (and this is the Roman Catholic doctrine) there was a “prevenient grace” which enabled, but did not compel, faith to arise from an incompletely fallen “will,” thus the launching the opportunity but not the guarantee of a life of sanctification ending worthy of entering (after “purgatory”) the eternal realm of heaven. There are other distinctions, of course, such as the significance of “the sacraments” and “the church” in enabling / causing such sanctification.

What we wish to highlight here because of its central importance in understanding Calvin’s “Little Book” is that Calvin, and the Reformers, hold to the doctrine that “Justification” occurs first, and the never ending process (in this life) of Sanctification, follows.

The Reformation which began, arguably, in 1517 with Luther’s posting of his 95 Theses, and grew mightily in the later years of the 16th Century led in many ways by the Geneva Reformers and Calvin’s publication of the Institutes, grew / matured into the 17th Century culminating in a series of great “Confessions.” These confessional documents are, principally: The Westminster (WCF, 1647), The Savory (SDFO, 1658), the London Baptist (LBCF, 1680), and The Philadelphia (PCF, 1742). I have discussed this more fully here:

The subject of Sanctification is dealt with succinctly, precisely, and beautifully in Chapter 13 of each of these Confessions as shown below:

| WCF — Chapter XIII: Of Sanctification | SDFO — Chapter XIII: Of Sanctification | LBCF/PCF — Chapter XIII: Of Sanctification |

|---|---|---|

| 1. They who are effectually called and regenerated, having a new heart and a new spirit created in them, are further sanctified, really and personally, through the virtue of Christ’s death and resurrection, by his Word and Spirit dwelling in them; the dominion of the whole body of sin is destroyed, and the several lusts thereof are more and more weakened and mortified, and they more and more quickened and strengthened, in all saving graces, to the practice of true holiness, without which no man shall see the Lord. | 1. They that are united to Christ, effectually called and regenerated, having a new heart and a new spirit created in them, through the virtue of Christ’s death and resurrection, are also further sanctified really and personally through the same virtue, by his Word and Spirit dwelling in them; the dominion of the whole body of sin is destroyed and the several lusts thereof are more and more weakened, and mortified, and they more and more quickened, and strengthened in all saving graces, to the practice of all true holiness, without which no man shall see the Lord. | 1. They who are united to Christ, effectually called, and regenerated, having a new heart and a new spirit created in them through the virtue of Christ’s death and resurrection, are also farther sanctified, really and personally, through the same virtue, by His Word and Spirit dwelling in them; the dominion of the whole body of sin is destroyed, and the several lusts thereof are more and more weakened and mortified, and they more and more quickened and strengthened in all saving graces, to the practice of all true holiness, without which no man shall see the Lord. |

| 2. This sanctification is throughout in the whole man, yet imperfect in this life: there abideth still some remnants of corruption in every part, whence ariseth a continual and irreconcilable war, the flesh lusting against the Spirit, and the Spirit against the flesh. | 2. This sanctification is throughout in the whole man, yet imperfect in this life; there abideth still some remnants of corruption in every part; whence ariseth a continual and irreconcilable war, the flesh lusting against the Spirit, and the Spirit against the flesh. | 2. This sanctification is throughout the whole man, yet imperfect in this life; there abideth still some remnants of corruption in every part, whence ariseth a continual and irreconcilable war; the flesh lusting against the Spirit, and the Spirit against the flesh. |

| 3. In which war, although the remaining corruption for a time may much prevail, yet, through the continual supply of strength from the sanctifying Spirit of Christ, the regenerate part doth overcome: and so the saints grow in grace, perfecting holiness in the fear of God. | 3. In which war, although the remaining corruption for a time may much prevail, yet through the continual supply of strength froin the sanctifying Spirit of Christ, the regenerate part doth overcome, and so the saints grow in grace, perfecting holiness in the fear of God. | 3. In which war, although the remaining corruption for a time may much prevail, yet through the continual supply of strength from the sanctifying Spirit of Christ, the regenerate part doth overcome; and so the saints grow in grace, perfecting holiness in the fear of God, pressing after an heavenly life, in evangelical obedience to all the commands which Christ as Head and King, in His Word hath prescribed them. |

Why is this treatment of Sanctification relevant here? In essence, Calvin’s “Little Book” summarizes in very practical terms what the process and experience of Sanctification is in the life of Justified believers. Justification comes first, and alone by Grace. This is made very clear in Calvin’s Institutes, but not completely in the five excerpted chapters of his Little Book we are using here. Of course the objection that is raised against this belief is that a man can express faith, and so give evidence of his “Justification,” but then live a life of no evidence that any such encounter with God’s Grace has taken place; the Epistle to the Hebrews, especially its Chapter 6, makes clear that such a life was never so “justified.” As Luther said of “Faith”–we are saved by faith alone but not a faith that is alone (i.e., dead)–can be directly applied to Justification, namely justification comes first, and alone by God’s Providential Grace, but it is not the end (the telos), but the beginning.

Hebrews 1:3 and Hebrews Ch 12

As I will address in a separate post, but repeat briefly here, the opening verses of the Epistle to the Hebrews makes absolutely clear to that audience, the Jewish people of the New Testament (NT) period, that following the Mosaic Law did not, could not, and would not ever lead to “Justification,” because by no work(s) of the flesh, including so-thought-to-be Law-following, can any man be justified, however dedicated or (appearing or believing to be) sincere. The Law condemns us all, and makes us ready to grasp the need for a Savior outside of ourselves, extra nos.

Consider Hebrews 1:3 given below:

3 He is the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature, and he upholds the universe by the word of his power. After making purification for sins, he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high,

Hebrews 1:3 (ESV, highlights mine: bold = are the 3 participles; underline = the one verb

There are so many wonderful dimensions of the above verse. Here we will focus only on the three participles and the one, main verb. The participles are identified by the bold font and the main verb by the underlining.

The first two participles are in the present “tense” (aka “aspect”). The most English-literal translations would be: “He, Being the radiance of…,” and “He upholding the universe…” Participles are verbs that are used as nouns, which often are formed in English by the -ing ending of word (but not exclusively so). The present tense (or aspect) is contrasted with the third participle–“making purification for sins”—which is in the Aorist tense (more on that tense below). The one verb, translated by two words–“sat down“–is also in the Aorist tense.

The Aorist tense can be considered the designation of a single, one-time, past act, such as “Fred was born in England.” Fred is only going to be born once (physically), so the Aorist tense in Koine is proper. However, modern scholarship stresses, over-stresses in my simple view, that the Aorist tense should not be primarily considered as a time marker but rather a whole event designation without a time element. So our example with Fred such view would so understand the word “born” in the Aorist form as signifying the notable news is that he was born and not that it was in the past, or that it was a one-time thing.

However, one-time past, and big-single event perspectives often coalesce as with Fred and much more significantly with the Koine verb “sat down” in Hebrews 1:3. It is the clear teaching of the Epistle that Christ’s sacrifice was a one-time, completed event, and from the perspective post-Resurrection that must be a one-time past event.

The Epistle to the Hebrews develops this line of understanding throughout the text. Consider this passage below from Chapter 9:

24 For Christ has entered, not into holy places made with hands, which are copies of the true things, but into heaven itself, now to appear in the presence of God on our behalf. 25 Nor was it to offer himself repeatedly, as the high priest enters the holy places every year with blood not his own, 26 for then he would have had to suffer repeatedly since the foundation of the world. But as it is, he has appeared once for all at the end of the ages to put away sin by the sacrifice of himself. 27 And just as it is appointed for man to die once, and after that comes judgment, 28 so Christ, having been offered once to bear the sins of many, will appear a second time, not to deal with sin but to save those who are eagerly waiting for him.

Hebrews 9 (ESV, emphasis mine, highlighting “once”)

So it is at Heb. 1:3 that we have the Aorist tense telling us that Christ “sat down” to signify the once and for all completed event of the payment for sin.

Now back to the three participles. The first two as noted are in the present tense, whereas the third is in the same Aorist tense as the main verb. The usual rule of interpretation is that such Aorist tense participle–which is here “making purification for sins…”–is likewise a one time event, which maybe obscured by the use of the word “making” in English that could suggest that such is an ongoing, never ending act. However, it is the first two participles that are in the present tense, “Being” and “upholding,” which rightly conveys the ever active, always present situation, namely Christ “Being the radiance of the glory of God” was, is and always will be the present situation, as is His “upholding.” So a better translation of this third participle is “made purification” where “made” is not a verb but a participle, a distinction not readily noted in English.

Note that the ESV reference to “the universe” as the object of Christs “upholding” is not a translation of any Koine mss word “universe;” the original mss says He is “upholding the all” (the all is “ta panta” which is literally “the all”). So whatever succeeds the present Creation upon the New Heavens and the New Earth will still be “ta panta,” but perhaps not “the universe” as we presently understand our physical place to be.

Returning now to Justification and then Sanctification claim, the above Heb. 1:3 verse is but a single example out of many possible texts gives us clarity as to God’s one-time completed satisfaction (“propitiation”) as the the sin debt we each carry from Adam and our own nature. We never reduce such debt, let alone eliminate it, by some lifetime of piety, even perfect piety (which of course would not even be possible). The debt has been paid for those for whom it has been paid. Now what?

Let’s consider further the chain of reasoning in the Hebrews Epistle, namely its Ch 12:

12 Therefore, since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses, let us also lay aside every weight, and sin which clings so closely, and let us run with endurance the race that is set before us, 2 looking to Jesus, the founder and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is seated at the right hand of the throne of God.

3 Consider him who endured from sinners such hostility against himself, so that you may not grow weary or fainthearted. 4 In your struggle against sin you have not yet resisted to the point of shedding your blood. 5 And have you forgotten the exhortation that addresses you as sons?

“My son, do not regard lightly the discipline of the Lord,

nor be weary when reproved by him.

6 For the Lord disciplines the one he loves,

and chastises every son whom he receives.”7 It is for discipline that you have to endure. God is treating you as sons. For what son is there whom his father does not discipline? 8 If you are left without discipline, in which all have participated, then you are illegitimate children and not sons. 9 Besides this, we have had earthly fathers who disciplined us and we respected them. Shall we not much more be subject to the Father of spirits and live? 10 For they disciplined us for a short time as it seemed best to them, but he disciplines us for our good, that we may share his holiness. 11 For the moment all discipline seems painful rather than pleasant, but later it yields the peaceful fruit of righteousness to those who have been trained by it.

12 Therefore lift your drooping hands and strengthen your weak knees, 13 and make straight paths for your feet, so that what is lame may not be put out of joint but rather be healed. 14 Strive for peace with everyone, and for the holiness without which no one will see the Lord. 15 See to it that no one fails to obtain the grace of God; that no “root of bitterness” springs up and causes trouble, and by it many become defiled; 16 that no one is sexually immoral or unholy like Esau, who sold his birthright for a single meal. 17 For you know that afterward, when he desired to inherit the blessing, he was rejected, for he found no chance to repent, though he sought it with tears.

Hebrews Ch 12 (ESV)

The order of revelation in the Epistle is important. The above chapter clearly occurs as a concluding admonition, in Ch 12 of its 13 chapters, exactly as Romans 12, Ephesians 4, and Colossians 3 are positioned: after the indicatives (verb forms that are statements of fact, including the fact of our completed redemption and new birth) then are given the imperatives (the verb forms of commandments for being, doing, going–consistent with and deriving from the indicatives preceding).

Martyn Lloyd Jones on Sanctification re Justification

Martyn Lloyd Jones (MLJ) taught a 12-year, Friday evening study of the Epistle to the Romans, in the mid-1900s, at Westminster Chapel in London.

In his commentary on various texts of Romans Chapter 8, he makes extensive reference to various false doctrines of Sanctification. These are all excellent, detailed reviews of these alternatives in the context of the clear teaching of all of Romans, particularly Chapters 5-8, but especially of Chapter 8:12-13. The text of this passage is below, followed by links to several of MLJ’s messages based on them and the subject of sanctification:

12 So then, brothers, we are debtors, not to the flesh, to live according to the flesh. 13 For if you live according to the flesh you will die, but if by the Spirit you put to death the deeds of the body, you will live. 14 For all who are led by the Spirit of God are sons of God. 15 For you did not receive the spirit of slavery to fall back into fear, but you have received the Spirit of adoption as sons, by whom we cry, “Abba! Father!” 16 The Spirit himself bears witness with our spirit that we are children of God, 17 and if children, then heirs—heirs of God and fellow heirs with Christ, provided we suffer with him in order that we may also be glorified with him.

Romans 8 (ESV)

Resources for Section 4.4, Week #16, are here:

Calvin’s Little Book, Week #14

This week we’ll do a first pass through Sections 1-3 of Calvin’s Chapter 4 (corresponding to Beveridge Book 3, Chapter 9).

Calvin has much to say about the World’s evils, our attraction to it, and our proper response away from it toward God. I have collected these observations on a special topic page, here:

Calvin’s Headings

Calvin’s headings for this Chapter 4, and for Sections 1-3 (from Beveridge’s translation) are as below:

Of Meditating on the Future Life

The three divisions of this chapter,—

I. The principal use of the cross is,

that it in various ways accustoms us to despise the present,

and excites us to aspire to the future life,

Sec. 1, 2. II. In withdrawing from the present life we must neither shun it nor feel hatred for it; but desiring the future life, gladly quit the present at the command of our sovereign Master,

Sec. 3, 4. III. Our infirmity in dreading death described.

The correction and safe remedy, Sec. 6.Sections

1. The design of God in afflicting his people.

To accustom us to despise the present life. Our infatuated love of it.

Afflictions employed as the cure.

To lead us to aspire to heaven.2. Excessive love of the present life prevents us from duly aspiring to the other.

Hence the disadvantages of prosperity. Blindness of the human judgment.

Our philosophising on the vanity of life only of momentary influence.

The necessity of the cross.3. The present life an evidence of the divine favour to his people;

Calvin, J., & Beveridge, H. (1845). Institutes of the Christian religion (Vol. 2, p. 285). Edinburgh: The Calvin Translation Society.

and, therefore, not to be detested. On the contrary, should call forth thanksgiving.

The crown of victory in heaven after the contest on earth.

Calvin’s Supporting Bible Texts

The verses Calvin cites supporting these sections included in the D&P translation are as below:

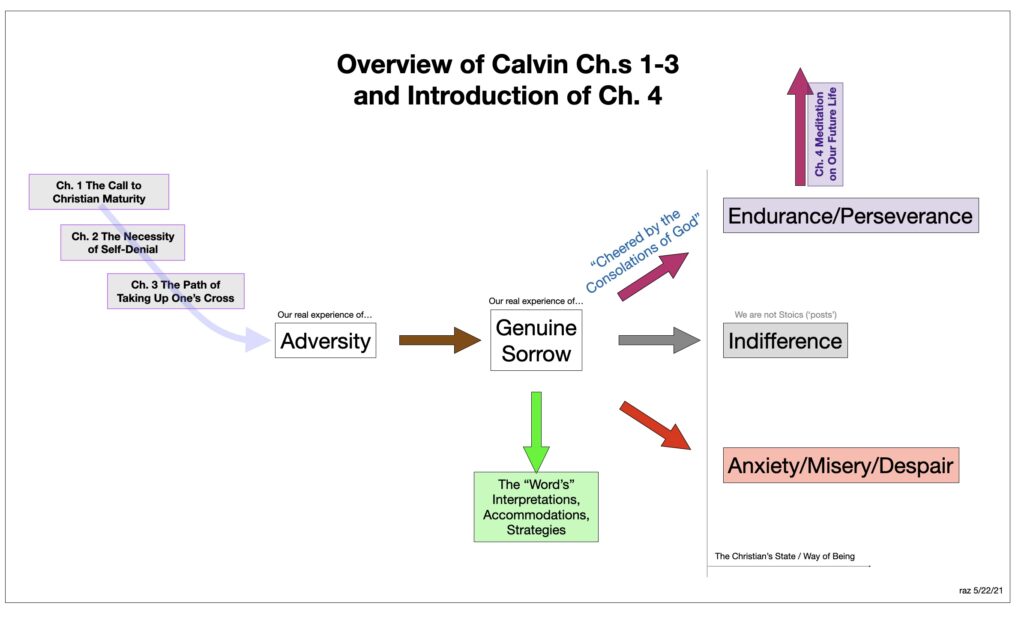

Overview of Chapters 1-3 and Introduction of Chapter 4

A graphic that will assist this overview of what we’ve covered and the chapter ahead is given below:

Experience of Adversity?

It might be imagined that the call of God coupled with the Providence and Love of His Character makes for smooth living here and now, every day, in every way. The Scriptures, and clearly Calvin in his Ch.s 2 and particularly 3, say otherwise. Exactly opposite otherwise.

Consider just this sample of descriptors Calvin used for the adversities of life:

- The mire of our love of this world

- Dulled by the blinding glare of empty wealth, power, and honor

- Hearts burdened with greed, ambition, and lust for gain

- Entangled in the enticements of the flesh

- This wickedness: the emptiness of this present life.

- Suffering, troubled, harassed by wars, uprisings, roberries

- Greediness toward frail and towering riches, yet experiencing poverty

- Exile, barrenness of land

- Fire and other means of destructive forces on what we may have

- Frustrated by the offenses of our spouse

- Humbled by the wickedness of our children

- Loss even of a child

- Life of disease, danger, that is unstable, fleeting

- Being troubled in turbulence of many miseries, never entirely happy

- Life that is uncertain, passing, vain, spoiled, mixed with many evils

- The fearful expectation of nothing other than trouble in this life

- All prone to leading to scorn for this present life.

(And all of the above is from Calvin’s first Section of Ch 4).

Experience of Genuine Sorrow?

What then of the adversity that enters our life, again, especially in the context of our having taken up the Cross? Clearly Calvin, and Scripture especially considered comprehensively, says yes indeed we do experience genuine sorrow.

In the below pdf are some additional verses from the Bible on sorrow. Though far from a complete list it gives a clear indication that sorrow is an experience God’s children undergo, some more than others, and differently than others.

As shown in the above chart, I am distinguishing between “genuine sorrow” and a bad place to live and be, namely the very unholy (and unbiblical) ‘trinity’ of anxiety, misery, and despair. But, still, is there genuine sorrow in a Christian life particularly one which is living seeking the Lord’s Will? The answer is yes. Consider:

SORROW Emotional, mental, or physical pain or stress. Hebrew does not have a general word for sorrow. Rather it uses about 15 different words to express the different dimensions of sorrow. Some speak to emotional pain (Ps. 13:2). Trouble and sorrow were not meant to be part of the human experience. Humanity’s sin brought sorrow to them (Gen. 3:16–19). Sometimes God was seen as chastising His people for their sin (Amos 4:6–12). To remove sorrow, the prophets urged repentance that led to obedience (Joel 2:12–13; Hos. 6:6).

The Greek word for sorrow is usually lupe. It means “grief, sorrow, pain of mind or spirit, affliction.” Paul distinguished between godly and worldly sorrow (2 Cor. 7:8–11). Sorrow can lead a person to a deeper faith in God; or it can cause a person to live with regret, centered on the experience that caused the sorrow. Jesus gave believers words of hope to overcome trouble, distress, and sorrow: “I have told you these things so that in Me you may have peace. In the world you have suffering. Be courageous! I have conquered the world” (John 16:33 HCSB).

Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary

GRIEF AND MOURNING Practices and emotions associated with the experience of the death of a loved one or of another catastrophe or tragedy. When death is mentioned in the Bible, frequently it relates to the experience of the bereaved, who always respond immediately, outwardly, and without reserve. So we are told of the mourning of Abraham for Sarah (Gen. 23:2). Jacob mourned for Joseph, thinking he was dead: “Then Jacob tore his clothes, put sackcloth around his waist, and mourned for his son many days. All his sons and daughters tried to comfort him, but he refused to be comforted. ‘No,’ he said. ‘I will go down to Sheol to my son, mourning.’ And his father wept for him” (Gen. 37:34–35 HCSB). The Egyptians mourned for Jacob 70 days (Gen. 50:3). Leaders were mourned, often for 30 days: Aaron (Num. 20:29), Moses (Deut. 34:8), and Samuel (1 Sam. 25:1). David led the people as they mourned Abner (2 Sam. 3:31–32).

Mary and Martha wept over their brother Lazarus (John 11:31). After Jesus watched Mary and her friends weeping, we are told, “Jesus wept” (John 11:35). Weeping was then, as now, the primary indication of grief. Tears are repeatedly mentioned (Pss. 42:3; 56:8). The loud lamentation (wail) was also a feature of mourning, as the prophet who cried, “Alas! My brother!” (1 Kings 13:30; cp. Exod. 12:30; Jer. 22:18; Mark 5:38).

Sometimes they tore either their inner or outer garment (Gen. 37:29, 34; Job 1:20; 2:12). They might refrain from washing and other normal activities (2 Sam. 14:2), and they often put on sackcloth: “David then instructed … ‘Tear your clothes, put on sackcloth, and mourn over Abner.’ ” (2 Sam. 3:31 HCSB; Isa. 22:12; Matt. 11:21). Sackcloth was a dark material made from camel or goat hair (Rev. 6:12) and used for making grain bags (Gen. 42:25). It might be worn instead of or perhaps under other garments tied around the waist outside the tunic (Gen. 37:34; Jon. 3:6) or in some cases sat or lain upon (2 Sam. 21:10). The women wore black or somber material: “Pretend to be in mourning: dress in mourning clothes, and don’t anoint yourself with oil. Act like a woman who has been mourning for the dead for many years” (2 Sam. 14:2 HCSB). Mourners also covered their heads, “[David’s] head was covered, and he was walking barefoot. All the people with him, without exception, covered their heads and went up, weeping as they ascended” (2 Sam. 15:30 HCSB). Mourners would typically sit barefoot on the ground with their hands on their heads (Mic. 1:8; 2 Sam. 12:20; 13:19; Ezek. 24:17) and smear their heads or bodies with dust or ashes (Josh. 7:6; Jer. 6:26; Lam. 2:10; Ezek. 27:30; Esther 4:1). They might even cut their hair, beard, or skin (Jer. 16:6; 41:5; Mic. 1:16), though disfiguring the body in this way was forbidden since it was a pagan practice (Lev. 19:27–28; 21:5; Deut. 14:1). Fasting was sometimes involved, usually only during the day (2 Sam. 1:12; 3:35), typically for seven days (Gen. 50:10; 1 Sam. 31:13). Food, however, was brought by friends since it could not be prepared in a house rendered unclean by the presence of the dead (Jer. 16:7).

Not only did the actual relatives mourn, but they might hire professional mourners (Eccles. 12:5; Amos 5:16). Reference to “the mourning women” in Jer. 9:17 suggests that there were certain techniques that these women practiced. Jesus went to Jairus’s house to heal his daughter and “saw the flute players and a crowd lamenting loudly” (Matt. 9:23 HCSB).

Drakeford, J. W., & Clendenen, E. R. (2003). Grief and Mourning. In C. Brand, C. Draper, A. England, S. Bond, & T. C. Butler (Eds.), Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary (pp. 690–691). Nashville, TN: Holman Bible Publishers.

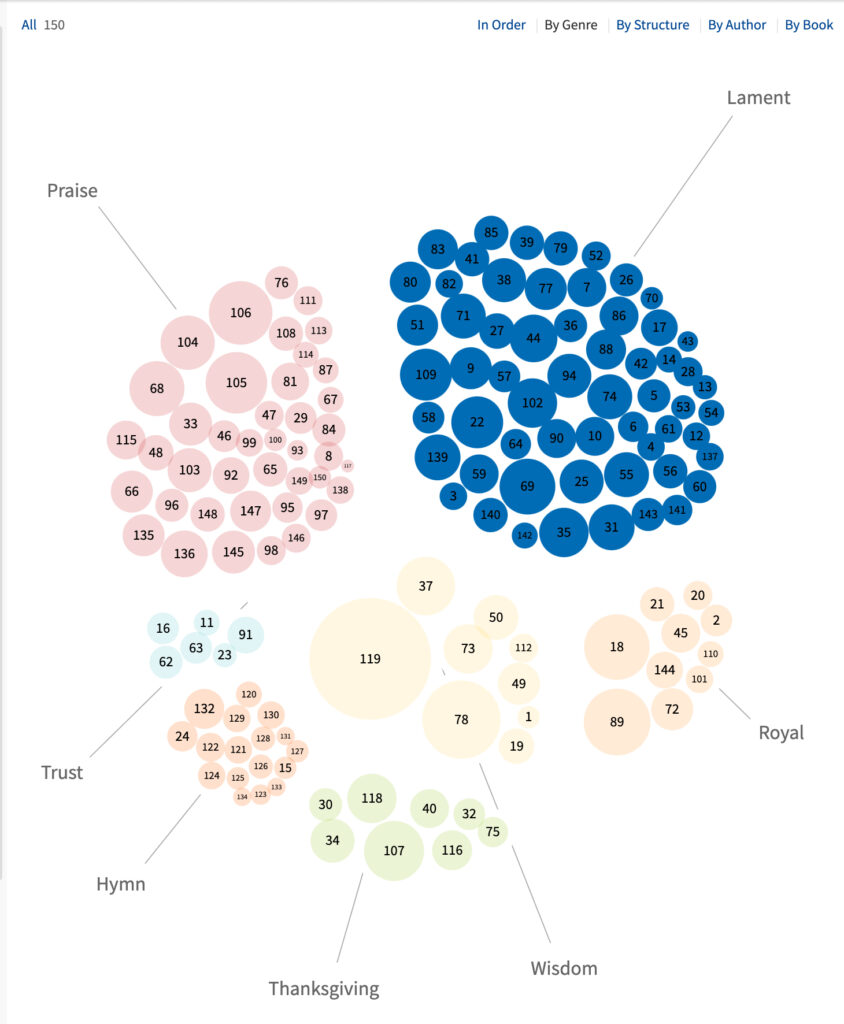

Consider the Book of Psalms. One useful perspective is to group the 150 individual Psalms by genre such as the seven categories shown in the graphic below (taken from a useful feature in Logos Software). Of these seven, the genre of “lament psalms” is clearly the largest (59 are considered to be in this category) and the subset of these termed “grief-lament” includes 43 psalms. The Psalms typically considered to be “encouragement psalms” number just 10, but eight of these 10 belong to the genre of “lament psalms,” showing that true encouragement commonly, and most reasonably, occurs in the context of lament or more specifically “grief” (sorrow):

Finally, consider the Greek word commonly translated “sorrow” in the New Testament. The graphic below (from Logos Software) show four forms of the root word “lúpē” that occurs 19 times, and a 20th word “odúnē.”

Further insight on the Greek word lúpē is given below. Note the many New Testament synonyms for this word indicating prevalence of the experience in multifaceted forms:

G3077. λύπη lúpē; gen. lúpēs, fem. noun. Grief, sorrow (Luke 22:45; John 16:6, 20–22; Rom. 9:2; 2 Cor. 2:1, 3, 7; 7:10; 9:7; Phil. 2:27; Heb. 12:11; Sept.: Gen. 42:38; Jon. 4:1). Metonymically for cause of grief, grievance, trouble (1 Pet. 2:19; Sept.: Prov. 31:6).

Deriv.: alupóteros (253), less sorrowful; lupéō (3076), to make sorry; perílupos (4036), surround with grief.

Syn.: katḗpheia (2726), a downcast look expressive of sorrow; odúnē (3601), pain, distress, sorrow; ōdín (5604), a birth pang, travail; pénthos (3997), mourning; stenochōría (4730), anguish, distress; thrḗnos (2355), wailing, lamentation; kópos (2873), weariness; sunochḗ (4928), anxiety, distress; básanos (931), torture, torment; pónos (4192), pain; tarachḗ (5016), disturbance, trouble; thlípsis (2347), tribulation, affliction; thórubos (2351), disturbance.

Ant.: chará (5479), joy; agallíasis (20), exultation, exuberant joy; euphrosúnē (2167), gladness.

Zodhiates, S. (2000). The complete word study dictionary: New Testament (electronic ed.). Chattanooga, TN: AMG Publishers.

Therapeutic Value of Sorrow?

One cause of sorrow is that of being excluded, even exiled. In our judicial system we have a constitutional prohibition against “cruel and unusual punishment.” The origin of such prohibition goes back to the use of torture in many forms as part of the penal system of the nations of Europe from which our constitution evolved.

But one form of penal punishment that is allowed is “solitary,” or “the hole,” whereby a prisoner is put in isolation for a time, perhaps a long time. In other contexts such isolation would be considered a positive: being put in a hotel room with a co-worker is less preferable to having one’s own room. How, then is isolation, separation, an added punishment for a prisoner?

The answer seems to be that we are innately social beings, though not necessarily 24 hours a day, or in all places or on everyday. But being ‘cut out’ of contact, excluded from belonging, can be a source of great sorrow. Such occurs even with children and teens as to their social groups, or the infamous ‘cool kids table’ at the high school lunch room. But it continues through all of life. And in these years of 2020-21 under pandemic restrictions of travel and association many have experienced despair in such isolation, despite all manner of online information resources and even people-‘connection.’

If we’d like to be able to be part of whatever group, club, society, what is required of us? What’s the admittance ‘fee?’ Depending on the group, such ‘fee’ can be so large as to be unachievable in our circumstance (which is likely why it exists). In many cases, the ‘fee’ is some version of conformity. We, body and perspective / values, need ‘to fit’ with the group.

Following the path to Christian Maturity, a title sometimes used of Calvin’s Little Book, and is the theme of its First Chapter, necessarily leads to perspectives, ideas, values that “the world” (Kosmos) will emphatically deem to be incompatible with it. The Scriptures make clear, there is darkness and there is light and the darkness hates the light, and flees from the light, because its deeds are evil. The likely favorite verse of Christians is John 3:16; but that verse heads an important paragraph as below:

16 “For God so loved the world,[i] that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life.17 For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him.18 Whoever believes in him is not condemned, but whoever does not believe is condemned already, because he has not believed in the name of the only Son of God. 19 And this is the judgment: the light has come into the world, and people loved the darkness rather than the light because their works were evil. 20 For everyone who does wicked things hates the light and does not come to the light, lest his works should be exposed. 21 But whoever does what is true comes to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that his works have been carried out in God.”

Gospel of John, Chapter 3, ESV

So, choosing, especially loving, such light excludes a person from the darkness-loving world (Kosmos). What can make this a cause fo Christian sorrow is that many of such groups are not evil in the sense of fleshy wickedness, but are aligned opposed to God to follow the wills of their self. We, too, full of “self” as well, can easily be drawn to such groups, as Lot was when he chose to leave Abram, as was Lot’s wife after she came to experience to the prosperity of the river valley civilization as it was then in the lower Jordan River valley.

Being excluded may cause us sorrow, but such should be so to protect us from a worse adversity, turning from God to adopt the perspectives and values of the world’s system.

Spurgeon on “Sorrow”

Charles Spurgeon was one of the great preachers of the 19th Century. Fourteen of his sermons dealt with the subject of “genuine sorrow.” A pdf of his sermon on “Sanctified Sorrow” is directly below. It has a the traditional three-part format, where each corresponds to the major phases of “life,” from new creation to physical death.

Another example Spurgeon message, this one “Sorrow and Sorrow” is below:

The context of Spurgeon’s message “Sorrow and Sorrow” is sin leading to true, Godly sorrow and repentance and to true joy. So, such sorrow is of a different character than the subject of Calvin’s Chapter 2 and especially Chapter 3, which derives from adversity, but not adversity that derives from sin. However, I’ve included it here because Spurgeon, as is his characteristic, makes many insightful observations. Some nuggets from the above message are below:

There are twin truths “that lie side by side, like the metals [rails] on which the railway carriages ride. These are, in the context of coming to Christ: (1) the emphasis on the need for repentance, true and deep, as proclaimed by “those experimental [experience-driving] preachers” intending to produce “very sturdy Christians” by “deep ploughing” (into one’s sin and hopeless condition) before “they begin to sow the good seed of the kingdom;” and (2) the simple proclamation of the Gospel message “Believe, and live,” emphasizing the sowing, sometimes “all sowing and no ploughing.”

How to reconcile the two? There is nothing to be reconciled, as they are both true and taught in Scripture as Luther meets Calvin as did Paul meets James. (In our contemporary culture the term “easy believism” has arisen and been applied to the preachers of the second ‘rail’ only).

Man’s fallen condition, which is never fully grasped apart from the revelation of God is without “life” but “the charnel-house of man’s corruption” from which “you shall never be able to discern any remedy for a sin-sick soul.” A “charnel-house” is a perfect description as it was the place in which unclaimed skeletons were piled, such as might be found when digging up a foundation; churches of that day would have such an out-building known by that term. It came to symbolize the ultimate sorrow of irreversible death. It is worth reading this message just for the paragraph containing such imagery.

What makes certain “sorrow”…”Godly sorrow?” Spurgeon puts it this way: “”the godly sorrow [is that] which worth repentance to salvation,” that is, “it is an agent employed in producing repentance, but it is not itself repentance.” Thus, “in the world, a great deal of sorrow on account of sin which is certainly not repentance, and never leads to it,” because such sorrow is of sin’s consequences–be they psychic, social, criminal or eternal–as without such consequences the person exhibiting this form of sorrow would gladly return to their sin.

Another mistake made by many–that this sorrow for sin only happens, once–as a sort of squall, or hurricane….” Spurgeon freely confesses “that I have a very much greater sorrow for sin today than I had when I came to the Savior…” as “sorrow for sin is a perpetual rain, a sweet, soft shower which, to a truly gracious man, lasts all his life long.”Spurgeon notes another common misunderstanding “that sorrow for sin is a miserable feeling.” Rather, he says, “there is a sweet sorrow, a healthy sorrow.” Spurgeon exhorts “come, brother, come sister, you and I cannot afford to live at a distance from Christ. We cannot afford to live in a state of misery,” that which results from not using “sorrow” to bring us closer to Christ.

The seriousness of sin as an evil directly against God is what maturity brings to awareness. We are attuned to wrongs we do against another person or against the society of people (i.e, a crime), but the world does not see evil acts against the will of God as being as that serious, “but,” Spurgeon says, “the essential thing is to be sorry because the evil is a wrong done to God.” “…when a man is really awakened, he sees the gravamen of the offense.” “Gravamen” is another word worth looking up: it comes from the Latin gravere, meaning to weigh down, from which we get our scientific term “gravity,” and was used of a legal complaint, or grievance, that was a basis of a legal action (lawsuit), an offense deserving of penalty of judgment.

Spurgeon expounds further on repentance as it means a fundamental change of mind “about everything, and especially about sin. A man is so sorry for having done wrong that he thinks differently now of all wrong-doing. He thinks differently of his entire life…to live just the opposite way to that in which has formerly lived.”

Further, Spurgeon notes that repentance causes us to expand our concept of sin and evil, introducing the phrase “purlieus of iniquity.” “Purlieus” is no longer a common term but it is worth understanding its meaning and application. In England from the middle ages (and likely even earlier), down to Spurgeon’s time (1834-1892), had certain very notable laws about the “forest” land, certain of which related to the rights of nobility as to hunting and so forth. The question then naturally follows as to exactly where does “the forest” end? So the word “purlieus” developed into an important legal term meaning the area adjacent to “the forest,” that may or may not have isolated trees, shrubs, and such, was part of “the forest.” Spurgeon’s use is insightful because our human tendency is to defined sin as narrowly as possible, in part to shrink it, and perhaps in part because we’d like to get close enough to it to peer over, as it were, the boundary and see the goings on without feeling that we are doing the evil. “Purlieus of iniquity” helps us think of the evil of the close association with that which is more clearly demarcated as “evil.”

As a final Spurgeon term of art is his phrase “the smart of sin.” “Smart” here has nothing to do with with “wise,” but the sting, the immediate sharp pain. The root of this word means quick, active, so we apply it to quick learners. But sin, and the guilt and sorrow from it, can have that kind of effect, an immediacy of experience, and a painful one.

The above are my notations of Spurgeon’s direct phrases shown in quotations, all based upon the publication of a sermon Spurgeon gave on Sunday Evening, July 31, 1881. How wonderful it would have been to sat there and heard his powerful, unamplified voice fill the Metropolitan Tabernacle in Newington (area now known as Elephant and Castle), England. For the history of the Tabernacle see here:

The “World’s” Accommodations, Strategies, Helps

The universality of the experience of adversity and genuine sorrow has led to many, multivariate accommodations, strategies, helps, explanations, ‘solutions.’ Examples? The entire history of man starting with Adam & Eve’s hiding with fig leaves give us countless examples, which emerge and re-emerge to this day, everywhere, and in every context.

Let us very briefly consider some major categories. Our purpose here is certainly not to make the case for any of these, though some more than others contain a certain space-time ‘wisdom.’ But they are all woefully inadequate to the Call, Self-Denial, and the Cross. Further, they all express in some essential way the will of man, independent of God, to make his way, as did Cain and his descendants in building their city whose pinnacle can reach to the heavens in some sense of saying to God Himself: “So there! We’ve done this without and despite You!”

Drugs, Sex, Rock n’ Roll

This is the old ‘standby’ for suppressing unhappiness while giving a temporary illusion of happiness, contentment. A close relative is “entertainment” in whatever form: sports, movies, TV, the internet ‘vortex’ (social media, YouTube, blogs).

The goal of the producers / providers of such is: (1) make themselves money, preferably a lot of it, by (2) by providing in trade one or two hours, perhaps more, during which a viewer can lose their ever-present consciousness of self-existence. Otherwise, as the saying goes, wherever you go…there you are. It is really hard for you to escape you. And when, as it does happen, it is for just a short period with the common result that you feel worse after than at the start, similar to sitting and eating a large tub of ice cream (another version of Drugs, Sex, Rock n’ Roll).

Happiness Project, Industry, Books, Formulas, Keys

Yes there exists “The Happiness Project” (researchers at University College, London), and numerous hyped books with ‘expert’ authors hyped continuously. Most of these are anecdotal, personal experience, or hypothesized keys–formulas even–to attaining a state of happiness.

Examples? Go outside. Sleep longer, better. Use stronger interior lighting, especially in dark climates or seasons. Exercise, even just walk a little. Call a friend. Love yourself, as in treat yourself as your best friend. Treat carbs as poison. Or, treat carbs as your friend (because, it is noted, that Jesus did not feed the 5,000 with fish and a side salad). Start a diary / journal to record your daily feelings and experiences. Play a musical instrument, sing a song, especially a happy one in a major key (C Major is always good; but stay away from B Flat). Put post note affirmations on your mirrors. Clean your room, make your bed. Be a learner, especially a lifelong learner. Stop being mean to people. But don’t be a pushover. Be generous. But, also look our for yourself. Do stretches, faithfully each day. Do daily tapping with both index fingers on your temple area. Whistle (but not with a “whistle”). Floss (don’t know the connection with happiness, but lots of people say this is important).

And, so forth. Fill up some 50,000 words of text about whatever comes into your head–and the previous paragraph is a good start–self-publish on Amazon, and, so, you have been self-made into an authority, literally (author-ity). Work social media. Post and promote regulary. Start a podcast. Maybe Oprah will invite you on to her show. Put a small assortment of Christian words and phrases, but be careful because you don’t want to lose the secular audience whose antenna are tuned to ‘hate speech,’ and you can sweep in a religious community of followers.

So, there is no reason to read any already published books or web searches. Just make up your own idealized version, and ‘go with it’ (but…it will be a road to nowhere, an aporia, but it may take a few years, decades even, to realize it).

Stoicism

Focus on the duty at hand, the way forward. Trudging forward, no matter what, is the way forward and keeps you from noticing that you are trudging.

Buddhism

Want nothing. Craving is the curse. Crave not, and you won’t be pained by having nothing. Nothing is good (it’s all ‘up’ from there).

Christian Science

Sickness is an illusion. It’s not real. So if you think you are sick, or getting so, the problem is you are thinking.

Rules of 100; 1,000; 10,000

Such “rules” are common propositions with the learning of new skills. Consider the simple example of learning to use a windsurfing board (a surf board with a sail on it). There are many challenges involved, beginning with just climbing up out of deep water onto the board without sliding over back into the deep. Then there’s the challenge of just standing and balancing. Then there’s raising the mast, and so on and so forth. Typical instruction is given using the rule of “100,” namely that there’s no “failure” (metaphor here for “sorrow”) because what is required for windsurf capability is 100 tries without success. So upon the first fall, which customarily occurs on the first try in the first half-minute, there’s a declaration of accomplishment because it is now “one down, 99 to go.”

Teachers and professors use similar “rules” to encourage new learners, such as a first course in a new language such as Spanish or Greek. Students are reminded that each semester of 15 weeks of three-classes a week, 45 nominal in class-contact hours, will be supplement by double that number with homework, making for 135 hours, after which time the student will be speak, read, write at a certain basic level. Then, in following up in a four year academic major would result in about 1,000 hours and a significant level of competency.

One author has written a book on the “rule” of 10,000 hours as being a common numeric standard for a high level of “mastery” in many different areas of life.

In all such frameworks, the guidance customarily given is there is no need for “genuine sorrow,” as it’s simply a matter of ‘reps’ (repetitions), earnestly done, with of course some innate level of capability / compatibility, that leads to achievement.

Performance Coaching

Coaches of individual sports like golf or tennis, and group sports like football, employe similar strategies to the above numeric rules. But further, they stress the absolute importance of looking forward to the next play or event, so as not to be captive to the adversity of a prior event leading to the related feeling of sorrow, grief, anxiety, fear. As they say, the game must go on, and so must every one seeking, at the end, to be declared the winner. So, for a golfer, for example, you cannot ‘carry’ a prior double boggy (a very bad score for a professional golfer on any given hole) with you on future holes and, so, affecting the individual golf swings that must now be made.

Happy Clappy ‘Gospel’ Church Hour

Just singing happy songs, with physical movement, in a community of happy people, or those compelled to fake it, makes one, after a time, as happy as the songs and the community itself. It can be similar to attending a Garth Brooks concert, but with needing an often hard-to-get ticket.

The Religion Industry (TRI)

A system of “religion” with its vestments, drama, even smells, all within the aura of a dramatic enclosure of height, span, and beauty can make one feel connected to something very big, and secure. TRI can be one’s protector in an uncertain world.

The Political Industry (TPI)

The system of community agreements that bind people and groups together can promise another kind of security, and even justice through the power of law and enforcement, including compulsory tribute paid to the common treasury.

The Call to Endurance / Perseverance

The Call of Ch. 1 from which we began this study in Calvin’s Little Book anticipated and included the central concept that our experience is to be a state of being, way of doing (and going) that reflects the character foundation of endurance / perseverance. (As discussed in previous Week’s, Calvin frequently uses the Latin word from which we get “moderation,” but its original meaning was to react alternatively to our natural human, space-time, impulse to flee from the experience, or to deny it, or strategize against it).

There is a Future, Ultimate Reality Beyond Full Human Comprehension

Now in this beginning of Chapter 4 in Calvin’s Little Book we will see a key to our endurance / perseverance that goes ever beyond the simple teaching of the Scriptures to be so, namely: there is something beyond our present space-time experience that is so so close that there are those moments in prayer and meditation with God when it, and He, seems more real than any human experience we’ve ever had.

Think of a womb-baby. He, or she, is just an inch or so from a world-reality incomprehensibly different from their present, though real, experience of “life.” Yet, in a very shot time, and with some reluctance, that little guy is thrust into the outer real life for which he has been conceived and formed. In just a few minutes the traverse occurs, often in travail (for both mom, even dad, and the little guy too).

Chapter 4, Sec. 1 (D&P p. 89ff) Key Points

The opening two sentences, the theme sentences, are (from the Beveridge translation, bold emphases are mine):

1. Whatever be the kind of tribulation with which we are afflicted, we should always consider the end of it to be, that we may be trained to despise the present, and thereby stimulated to aspire to the future life. For since God well knows how strongly we are inclined by nature to a slavish love of this world, in order to prevent us from clinging too strongly to it, he employs the fittest reason for calling us back, and shaking off our lethargy.

Calvin, J., & Beveridge, H. (1845). Institutes of the Christian religion (Vol. 2, p. 285). Edinburgh: The Calvin Translation Society.

The concluding two sentences of this section are below:

From this [the ever present evils of our space-time] we conclude, that all we have to seek or hope for here is contest; that when we think of the crown we must raise our eyes to heaven. For we must hold, that our mind never rises seriously to desire and aspire after the future, until it has learned to despise the present life.

IBID.

The above conclusion by Calvin is direct, even harsh: (1) this present life, properly faced while on the journey to Christian maturity is and will always be “contest” (discussed further below), and (2) for our eyes (and heart) to be properly directed to our future beyond and after space-time, we must learn to “despise” this life. This is the absolute opposite of “Your Best Life Now,” and every other version of the prosperity Gospel, and of the labyrinth of the world (Kosmos) seeking to entrap us (thus the “contest”).

“Contest”

Beveridge’s translation gives us “contest,” whereas D&P “trouble.” “Contest” does not work for our age as it calls up the idea of a sports game. “Trouble” doesn’t exactly work either as that encompasses flat tires, dropped phone calls, and the like.

A better word, in my judgment is “conflict.” Conflict captures the essential idea that the Light of the Gospel, the Bible as a whole, is, when properly understood and proclaimed, in a state of conflict with any worldview that is man-centered or, even worse, centered on a god of man’s conception.

Calvin used in his Latin original the word certāmen (-inis, noun, from the Lat. verb certo). The Latin word is used of a contest, a competition. But the idea I think Calvin was expressing, also encompassed by certamen is dispute, dissension (not in the sense of argumentation but as the expression of a foundational difference in life-view). Another suitable translation would be “dispute.” All of such ideas convey the always-existing opposition of ideas.

Philosophers frequently deal with such oppositions. One well-known and still prevalent perspective was formulated (or approximately so) by Hegel as: First, thesis; then antithesis; finally synthesis, known by Hegelian Dialectics.

One simple perspective on this view is that sustained conflict is a naturally unstable existence. Inevitably, something just gives way. So in the rub between an existing world view (the “thesis”) and an alternative, conflicting world view (the “antithesis’) is a form of resolution, accommodation (the “synthesis”). Which, according to the theory only leads to a new thesis from which there will inevitably arise a new antithesis and thus synthesis and so forth. The optimistic form of the dialect is that such process produces better world views, better worlds, better humans and their conditions for living. The 20th Century is 100 years of evidence challenging such optimism, and the 21st continues to do so.

However, in Biblical terms, the conflict, the certamen, began before space-time, with the Fall of Satan, began at the very onset of space-time, with the Fall of Man (Edenic Fall), continued to and through Jesus Christ presenting Himself as Messiah, and has continued every since, to this day, and will until the time and occasion of Revelation 22. If there is any “synthesis,” some attempt at peaceful coexistence, then either God has changed His mind about Evil, or the Devil has changed his mind about God. I’ll let the reader assess the possibility of such occurring.

“Despise”

The Beveridge translation has it that God has called us to “despise” this present life. D&P instead translates the idea as “scorn.” Calvin’s Latin was contemptu, which nominally can be translated by either despise or scorn, and is clearly the source of our word “contempt.”

The etymology of “contempt” is helpful to aid our understanding:

late 14c., “open disregard or disobedience” (of authority, the law, etc.); general sense of “act of despising, scorn for what is mean, vile, or worthless” is from c. 1400; from Old French contempt, contemps, and directly Latin contemptus “scorn,” from past participle of contemnere “to scorn, despise,” from assimilated form of com-, here probably an intensive prefix (see com-), + *temnere “to slight, scorn, despise,” which is of uncertain origin.

…Phrase contempt of court “open disregard or disrespect for the rules, orders, or process of judicial authority” is attested by 1719, but the idea is in the earliest uses of contempt.

https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=contempt

The proper idea of “contempt”–and scorn or despise–in our Biblical context is not that of being a superior looking down on worthless, stupid, evil inferiors, especially the people ‘on the other side.’ First, we need to recognize that there is one that is on the other side, the Evil One himself, and his devils, and spawn, which is does not extend to all the humans who at any given time may express their opposition to the Light of the Gospel, as did Saul before he became Paul, as did the many who cried “Crucify Him!” at the trial by Pilate. There is an intractable opposition that will never relent, never be transformed, and will always oppose even to torment and physical death (but no further, and not even to that stage without Providential Permission). There is no “meeting of the minds” possible in such case, without abandoning the essence of the Gospel, and of Christ Himself.

However, we note that the Lord Himself called down from the Cross of utter condemnation by the Evil One asking God the Father, a communication within the Trinity, that Christ was Himself offering Himself as the means of the Father’s forgiveness of those who do not know what they are doing. In the same way, Steven the Disciple, the first martyr, asked God not to hold accountable the men in religious ignorance who at that very moment were stoning him to death solely for his proclamation of the Gospel, to which they were then mortally opposed.

So, perhaps a better translation for despise / scorn would be an artful way of saying we are in a state of unending mortal combat, about the most important issues of reality, the Character of God, and of man, the only means of restoration / regeneration, and eternal destinies post the end of Space-Time. And there is no peace to be had in this life, though we will hear of many Neville Chamberlin’s proposing such (Chamberlin was the British Prime Minister who claimed he had achieve “peace in our time” because he had the signature of Adolph Hitler on a piece of paper he was waving around after having landed in England after such negotiations).

Spurgeon on Heaven

Charles Spurgeon spoke repeatedly about heaven, and our next life, some 37 distinct sermons by some count. Below is a Spurgeon illustration of what it will be like leaving earth for heaven:

The Earth Clings to Us Job 1:20–22

What is the use of all that clogs us here? A man of large possessions reminds me of my experience when I have gone to see a friend in the country and he has taken me across a plowed field, and I have had two heavy burdens of earth, one on each foot, as I have plodded on. The earth has clung to me and made it hard walking.

It is just so with this world. Its good things hamper us, clog us, cling to us, like thick clay. But when we get these hampering things removed, we take comfort in the thought, “We shall soon return to the earth from which we came.”

We know that it is not mere returning to earth, for we possess a life that is immortal. We are looking forward to spending it in the true land that flows with milk and honey, where, like Daniel, we shall stand in our lot at the end of the days. Therefore, we feel not only resigned to return to the womb of mother earth, but sometimes we even long for the time of our return to come.

Spurgeon, C. (2017). 300 Sermon Illustrations from Charles Spurgeon. (E. Ritzema & L. Smoyer, Eds.). Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press.

Spurgeon, C. (2017). 300 Sermon Illustrations from Charles Spurgeon. (E. Ritzema & L. Smoyer, Eds.). Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press.

Resources for Review of Little Book, Week #15 are here:

Resources for next Section in Ch 4, Week #16 are here:

Calvin’s Little Book, Week #12

This week we will be reading Calvin’s Little Book, Ch 3, Sec.s 7-9, pp. 72-29 in the Denlinger and Parsons translation.

Calvin’s headings for these sections as translated by Beveridge are below:

7. Singular consolation under the cross, when we suffer persecution for righteousness. Some parts of this consolation.

8. This form of the cross most appropriate to believers, and should be borne willingly and cheerfully. This cheerfulness is not unfeeling hilarity, but, while groaning under the burden, waits patiently for the Lord.

9. A description of this conflict. Opposed to the vanity of the Stoics. Illustrated by the authority and example of Christ.

Calvin, J., & Beveridge, H. (1845). Institutes of the Christian religion (Vol. 2, p. 273). Edinburgh: The Calvin Translation Society.

The verses cited by Calvin for these sections are given below:

The Believer’s War

Here Calvin brings out another perspective of the calling to the life of a mature Christian, namely that of being at war. This presents a challenging perspective as this chapter in Calvin is about bearing our cross as part of self-denial. “War” seems incongruous with “bearing our cross” and even with “self-denial.” But as we will see, there is a direct connection. And we need to see that in bearing our cross we are quite incapable, humanly speaking, of conducting such war, as we are of submitting ourselves to self-denial. The reconciliation occurs when we realize that “we” are not alone, and the true “we” is Christ in us. The presence of the cross makes it, or should make it, clear of the necessity of that union with Christ, as we saw in our study of Chapter 1.

In Week #11, there was provided two links to messages by the late Dr. Martyn Lloyd Jones from a parallel text (Romans 8) of the same concept of the inner war.

The Battle Armor of God (Ephesians 6)

In this chapter we are presented with an alternative application of the characteristic battle armor worn by the soldiers of the mighty Roman armies. The Apostle Paul is likely looking at and examining such gear directly from his place in his jail cell in Rome, and with which he is very familiar by virtue of his being confronted by it 24 hours a day, every day of the week, as he had been in one place or another since his arrest more than two year previously in the Temple area of Jerusalem (Acts 26).

Here is the text of Paul’s description and application of such armor that we, as soldiers of Christ, bear, should bear, and its purpose and use:

10 Finally, be strong in the Lord and in the strength of his might. 11 Put on the whole armor of God, that you may be able to stand against the schemes of the devil. 12 For we do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers over this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places. 13 Therefore take up the whole armor of God, that you may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done all, to stand firm. 14 Stand therefore, having fastened on the belt of truth, and having put on the breastplate of righteousness, 15 and, as shoes for your feet, having put on the readiness given by the gospel of peace. 16 In all circumstances take up the shield of faith, with which you can extinguish all the flaming darts of the evil one; 17 and take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God, 18 praying at all times in the Spirit, with all prayer and supplication. To that end, keep alert with all perseverance, making supplication for all the saints, 19 and also for me, that words may be given to me in opening my mouth boldly to proclaim the mystery of the gospel, 20 for which I am an ambassador in chains, that I may declare it boldly, as I ought to speak.

Ephesians 6:10-19 (ESV)

The ‘Armor’ of Hope

Looking ahead in Calvin’s Little Book, Chapters 4 and 5 (Beveridge, Book 3, Chapters 9 and 10) we can see that these are focused on our “Hope.” We need this reminder here, especially, in these sections of the “Bearing our Cross” chapter. So, this war is not forever, or even for very long in the true sense of time. And it is not unrelenting without consolation, encouragement, and engagement with fellow travelers, and with God Himself in prayer and primarily meditation, including meditation in the course of reading the Scriptures.

Persecution as Part of Bearing the Cross

In Sec. 9, Calvin recounts that the world’s response to anyone who “assert[s] God’s truth against Satan’s lies” including any support of the cause of “good” will “necessarily encounter the world’s displeasure and hatred.”

Such should be the Christian’s always expected condition. It is clearly in the New Testament, even by the model of Jesus Christ Himself. Texts we should consider include (all from the ESV):

John 3:19 And this is the judgment: the light has come into the world, and people loved the darkness rather than the light because their works were evil. 20 For everyone who does wicked things hates the light and does not come to the light, lest his works should be exposed.

John 3:19-20, The Holy Bible: English Standard Version. (2016). (Jn 7:7). Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles.

Matthew 11:20 Then he began to denounce the cities where most of his mighty works had been done, because they did not repent. 21 “Woe to you, Chorazin! Woe to you, Bethsaida! For if the mighty works done in you had been done in Tyre and Sidon, they would have repented long ago in sackcloth and ashes. 22 But I tell you, it will be more bearable on the day of judgment for Tyre and Sidon than for you. 23 And you, Capernaum, will you be exalted to heaven? You will be brought down to Hades. For if the mighty works done in you had been done in Sodom, it would have remained until this day. 24 But I tell you that it will be more tolerable on the day of judgment for the land of Sodom than for you.”

Matthew 11:20-24, ESV

The above passage from Matthew 11 is an astonishing pronouncement of judgement on many levels. But as to our issue here, these three Galilean cities–Chorazin, Bethsaida, and Capernaum–where Jesus directly ministered, taught, and healed by miracles for the better part of three years, all rejected, as cities of the whole, Jesus Himself and His teaching, though there were individuals who did believe and follow Him. And we know that at the final Passover of Jesus’s earthly life, when thousands of Jewish men were in attendance as required by the Old Testament Law, the scream from the crowds to Pilate’s ears was “Crucify Him!”

John 7:1 The world cannot hate you, but it hates me because I testify about it that its works are evil.

John 7:1, ESV

Jesus in the above passage from John 7 appears to say that the world is unable, or not permitted by God, to hate Jesus’s disciples, but Jesus Himself only. However, the grounds of the world’s hatred of Jesus is His proclamation that its deeds are evil. What deeds? There is no evidence that such deeds were what we typically consider as the carnal matters of the flesh (sex, drugs, and rock n’ roll, as they say). Rather the deeds at issue were religious ones, with the underlying false, but vehemently embraced, belief that such deeds had indeed earned personal and corporate righteousness from and of God, especially in contrast to all Gentile peoples everywhere including, especially the hated Romans. After Pentecost, the Apostles and others, down to us in our day, proclaim that same message hated still by the world, namely that it is only by Grace, and the finished work of Christ by which we are imputed as righteous before God. No form of “Law” as a principle of us gaining personal righteousness before God exists either from the Old or the New Testaments. It is by Grace, and anyone in any religious system undergirded by legal self-merit will hate such message.

24 Five times I received at the hands of the Jews the forty lashes less one. 25 Three times I was beaten with rods. Once I was stoned. Three times I was shipwrecked; a night and a day I was adrift at sea; 26 on frequent journeys, in danger from rivers, danger from robbers, danger from my own people, danger from Gentiles, danger in the city, danger in the wilderness, danger at sea, danger from false brothers; 27 in toil and hardship, through many a sleepless night, in hunger and thirst, often without food, in cold and exposure.

The Holy Bible: English Standard Version. (2016). (2 Co 11:24–27). Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles

.In the above passage the reference to “my people” refers of course to the Jewish people but more specifically to The Religion Industry (TRI) institution, much as Paul in his previous life as Saul was doing on behalf of TRI. And the “Gentiles” above is in reference to The Political Institution (TPI), namely the organized government, more so than individual Gentile individuals, which, like TRI, violently opposed any movement of people or ideas that threatened its incumbent powers.

25 who through the mouth of our father David, your servant, said by the Holy Spirit, “ ‘Why did the Gentiles rage, and the peoples plot in vain? 26 The kings of the earth set themselves, and the rulers were gathered together, against the Lord and against his Anointed’— 27 for truly in this city there were gathered together against your holy servant Jesus, whom you anointed, both Herod and Pontius Pilate, along with the Gentiles and the peoples of Israel, 28 to do whatever your hand and your plan had predestined to take place.

The Holy Bible: English Standard Version. (2016). (Ac 4:25–28). Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles.

The above passage shows the uniting of TRI with TPI to attack to extinguish (if possible) a common enemy, namely the Gospel message of Christ.

Persecution and Blessedness

Calvin cites one of the “Beatitudes” (which references the word “blessed” which begins each line of that passage) in the opening chapter of the Sermon on the Mount, in Matthew 5. This passage is provided in the pdf below:

Highlighted are the occurrences of an important Koine Greek word translated “blessed” and the source of the term “beatitude,” namely: markarios (Strong’s G3107). This word is so important. It is the very first word of the very first Psalm (Psalm 1:1 in the LXX, Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Old Testament). There the blessedness is the keeping of the believer from the three impulses to error, which is likely a reference to the false lures of TRI. Markarios is also the word used by the Lord of Peter’s great confession in Matthew 16–“Blessed are you Simon Peter”–because God Himself had revealed Jesus’s identity to Peter.

Calvin in Sec. 8 cites the passage in 1 Peter 4:14 that claims we are blessed (and it’s the word makarios used here also) if insulted for the name of Christ, whereby “the name of” references the full identify and work of Christ, with is contained in the Gospel. (There is an ancient compromise temptation that the world sometimes tries, namely: Jesus was a good man but not all these deep spiritual stuff; CS Lewis famously refutes this by his “trilemma:” Jesus was either insane, a voice of the Devil, or God Incarnate–He left us no other alternative including that of being just “a good man.”)

But how, exactly, in the above passage from the Sermon on the Mount, is mourning and sorrow, and experiencing persecution and reviling, a “blessed” thing? The answer, at least in part, links up with Calvin’s reference in this entire Chapter 3 of the Little Book with taking up the cross. And how is that a blessing? I suggest the answer is in our previous study of the shelter provided by God away from the labyrinth of the world’s system (be it TRI or TPI or in combination). Consider again the final chart we used then as given below:

One of the most power lines of attack of the Enemy against the Gospel is to sieze control of its truth so as to reshape it such that it’s meaning is distorted, even unrecognizable. The common strategy is syncretism, meaning the joining together of two separate camps, or ideas, to find common ground, compromise. One form of such temptation was used by Satan on Jesus in the wilderness. Another form appeared with the Judaizers in Galatia. Another form appeared with the carnal practices and doctrines in Corinth. Yet another in the Epistle to the Hebrews where (particularly in Chapter 6) the Jewish people who had been following the Gospel message, were being lured back into the ancient practices of Judaism as a call ‘home.’ In the judgments pronounced on the seven churches in Asia in Revelation Chapters 2 and 3, such compromise seems to be the universal ground of condemnation.

So, in such context, the absolute condemnation and rejection by the world’s system (TRI and TPI) causes us to seek and hold to the shelter of God’s provision, illustrated above, and not face the great temptation for compromising the purity of the Gospel message because no real, substantive part of such message will ever be acceptable to it.

Endurance

What then? If the world does and always will hate the message of the Gospel, and despise and persecute any proclaimers of it, how does all this play out over this age in which we live? The answer is that such will be the condition until the Lord’s Return and under which we are called to many things but including, and relevant here, our endurance. The word “endurance” only makes sense if there is something that cannot or will not change that is the cause of discomfort and sorrow.

In Section 9 Calvin addresses one of the common teaching errors, namely some form of Christian stoicism. The stoics were an ancient form of TRI, holding to a doctrine of remoteness and “indifferent to the vicissitudes of fortune and to pleasure and pain.” (OED definition). The essence of the teaching was not so much enduring such vicissitudes but being in an sense out of the reality of it so as to be un-affectable by misfortune.

Calvin clearly makes the case that our call to endurance is not about stoicism. Christian endurance feels the pain, the loss, that life can present especially when accompanied by injustice, specifically the suffering that can occur solely because of one’s faith God and His Word.

Note in the Beveridge translation the word “endurance” primarily used in D&P is instead expressed as “moderation,” which was more appropriate in the language of the 18th and 19th Century. Such word appears 48 times in the Beveridge translation, of Calvin’s Latin word moderatio which conveys “moderation” in the sense of “self-control,” here meaning that one does not respond to such persecution or other trials in accordance with how “self” would naturally do. The idea is restraining not one would commonly think of moderation as just being not in excess.

Resources for Week #13 are here:

Calvin’s Little Book, Week #11

This week we will continue our study of Self-Denial in connection with Bearing Our Cross, Ch. 3, Sec.s 5-6, pp. 67-71 in the D&P translation (Book 3, Chapter 8 in Beveridge’s translation)

Calvin’s heading for these two sections are as follows:

5. The cross necessary to subdue the wantonness of the flesh.

This pourtrayed by an apposite simile. Various forms of the cross.6. God permits our infirmities, and corrects past faults, that he may keep us in obedience. This confirmed by a passage from Solomon and an Apostle.

Calvin, J., & Beveridge, H. (1845). Institutes of the Christian religion (Vol. 2, p. 273). Edinburgh: The Calvin Translation Society.

The verses cited by Calvin are given below:

Understanding the Flesh: It’s Impulses, Works, Direction

D&P’s translation of the opening sentences uses “prone” and “cast off” to characterize the basic inclination of the flesh with regard to God’s direction, which is characterized by the word “yoke.” These are important ideas, so let us consider them further.

Prone

The idea of the word “prone” is the natural inclination of something or someone. A pencil balanced vertically on it’s eraser is very prone to fall. A glass very nearly full is prone to spill. Three year olds let loose in a room full of toys and stuff are prone to create chaos. In any lawn or garden the soil is prone to yield weeds.

What about us? What are we prone to do? And, more specifically, what are we prone to do with respect to our Creator-God?