Calvin’s closing chapter 5 in his Little Book is about living here and now, surround by and to at least to some extent needing, the temporary world to which we have been assigned. As we developed in Week #20, such living here and now is a balance, with slippery slopes on both side, between extreme asceticism on the one hand and licentiousness on the other. And, further to the errors of such opposite behaviors is an overlaying error, that of self-justification / self-exaltation, and underlaying both errors is yet another kind of error…pride. In the first case it is the pride of ascetic living which characteristically devolves into self-righteousness deriving from self-denial beyond what God has marked out either directly or by reasoned judgment from the Scriptures. In the second case it is the pride of “liberty” to do what “feels good” and to be proud of so doing it because “God is Love” and “Love is Love,” and whatever other mantra appears on the scene.

So, in this special topic, we have copied over some of the commentary from Week #20 on coveting to create a separate place where this matter can be considered more fully (as time permits).

Key Points from Week #20 on Coveting

In our previous weeks of study we saw Calvin make clear that we are privileged to enjoy the blessings of God in this life, bounded by several principles: the flesh cannot be the ruling authority of the scope of such enjoyment-seeking, what is rightfully enjoyed does not impede our journey to maturity and our heavenly home, and each enjoyment leads us to greater gratitude to God as the source of such delights.

Calvin began Ch 5.5 with the situation in which we may be in a condition of want. The danger here is coveting that which we do not have, and perhaps cannot have. This may include both those things and experiences which could be proper delights on our journey (Pilgrimage) and those which are not (the lusts of the flesh, and the eye).

The underlying issue here is “covetousness.” So let’s think about this word.

The Ten Commandments

An interesting exercise is to make a list of 10 universal principles of rightful behavior for a people living together, under God. What would you chose? What would you leave off?

The three obvious choices would include “no stealing,” “no murder,” “no violations of the sexual boundaries of marriage.” Clearly doing otherwise would dishonor God and our neighbor, even a visitor / stranger to one’s community. These would likely be choices made even by what we know to be criminal organizations. How is that? Well, such the members of such organizations are arrayed to commit “crimes” against “the other” (whatever group is such) but never within its own membership. And violations of such internal rules may be dealt with very harshly including killing the offender (which would not be deemed “murder” but justice, namely a lawful killing within the rules of the organization).

That leads seven more to go universal rules to make the 10. And now it is harder to pick out the obvious ones. Let’s see what God decreed:

Exodus 20:1 And God spoke all these words, saying,

2 “I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.

3 1 “You shall have no other gods before me.

4 2 “You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. 5 You shall not bow down to them or serve them, for I the Lord your God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who hate me, 6 but showing steadfast love to thousands of those who love me and keep my commandments.

7 3 “You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain, for the Lord will not hold him guiltless who takes his name in vain.

8 4 “Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy. 9 Six days you shall labor, and do all your work,10 but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God. On it you shall not do any work, you, or your son, or your daughter, your male servant, or your female servant, or your livestock, or the sojourner who is within your gates. 11 For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, and rested on the seventh day. Therefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy.

12 5 “Honor your father and your mother, that your days may be long in the land that the Lord your God is giving you.

13 6 “You shall not murder.

14 7 “You shall not commit adultery.

15 8 “You shall not steal.

16 9 “You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor.

17 10 “You shall not covet your neighbor’s house; you shall not covet your neighbor’s wife, or his male servant, or his female servant, or his ox, or his donkey, or anything that is your neighbor’s.”

18 Now when all the people saw the thunder and the flashes of lightning and the sound of the trumpet and the mountain smoking, the people were afraid and trembled, and they stood far off19 and said to Moses, “You speak to us, and we will listen; but do not let God speak to us, lest we die.” 20 Moses said to the people, “Do not fear, for God has come to test you, that the fear of him may be before you, that you may not sin.” 21 The people stood far off, while Moses drew near to the thick darkness where God was.

Exodus 20, ESV (enumeration mine)

So the obvious three are #6, 7, and 8 on God’s List of 10. Bracketing these three, at #5 and #9, are honoring one’s parents, which certainly includes positive affirmations of them, and which comes with a promised blessing for doing so, and #9 honoring our neighbors by never speaking falsehoods regarding them, which would of course dishonor them and do so wrongly. Now we have five governing principles.

Then we have the first four, #1, 2, 3, and 4, all of which honor God, including #4, a day set aside from the pursuit of one’s work (and agenda) to recognize the gifts and calling of God. In a humanist worldview, driven by the “science” of the “enlightenment,” it is very unlikely that any of these four would be recognized as life principles. Actually the contrary is more likely to be the case.

Now we have nine of the 10. What’s left?

You Shall Not Covet

Note the final Commandment above: “you shall not covet” given as to a comprehensive list of things you do not have at all or not in the form you desire:

- House

- Wife

- Servant(s) (human servants)

- Ox

- Donkey

- Anything (else) of your neighbor’s

Each of these distinctions have to be understood in the context of the time and place of the Law’s giving. Few of us live near, or are even aware of someone else’s “ox” or “donkey.” So not coveting such seems like a pretty easy command to obey. If “house” means only literal dwelling, and if we live as many do in ‘cookie-cutter’ housing of apartments or standard developments where each living unit is about the same as the other, this would also seem to be an easy matter. Likewise we do not have human servants in common practice, though people can be very possessive of their baby sitters, so that would also seem to be an easy issue. As to “wife” the fundamental issue is already given as #7 in the 10.

But then there’s the “anything.”

Further, we need to understand that “house” represents more than dwelling, but includes the means of income, i.e. production / business enterprise, that is part of a neighbor’s possession. And the “ox” represents the major tool of farming production, and “donkey” of transportation, and “servants” any of the machinery of daily life that aids the work of life such as would have associated with cooking, cleaning, obtaining water, dealing with garbage, shopping in the marketplace. And the reference to “anything” is to make clear that what is at issue is not the specifics of the enumeration of objects but the underlying attitude of one’s own heart. And that goes to the matter of coveting.

What Does it mean “To Covet?”

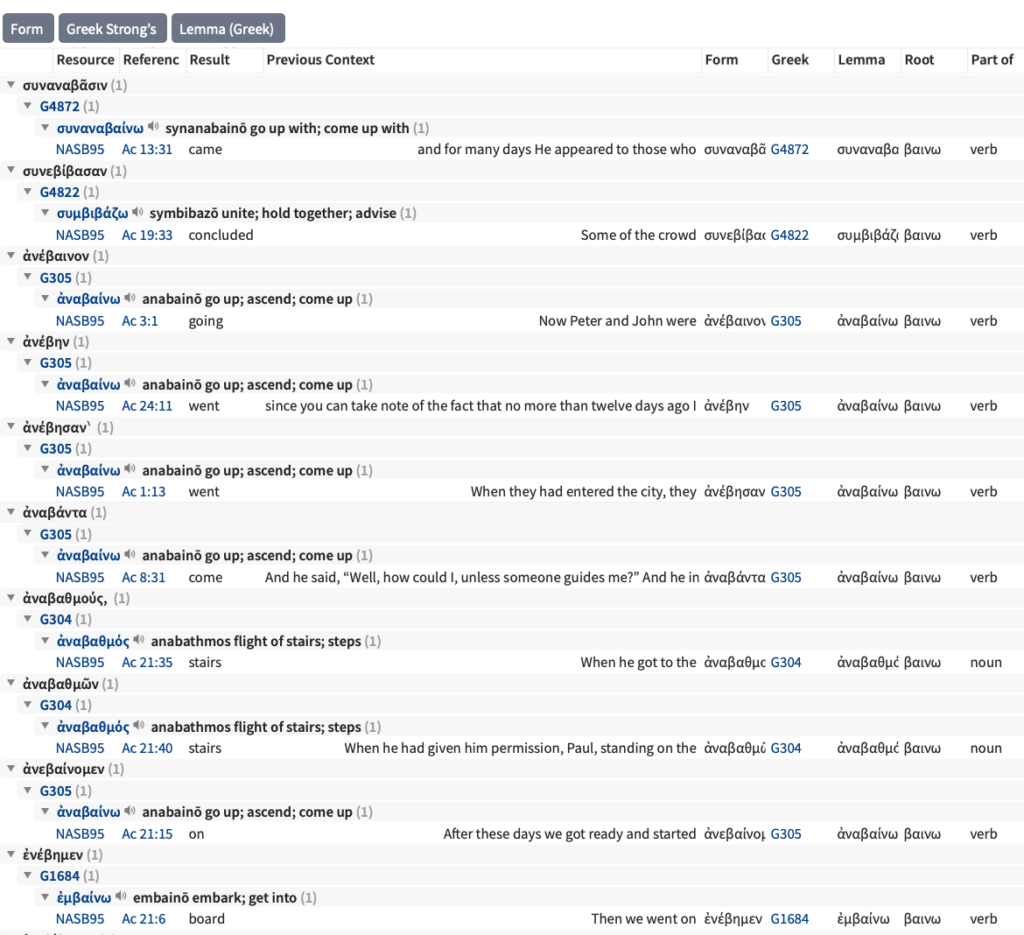

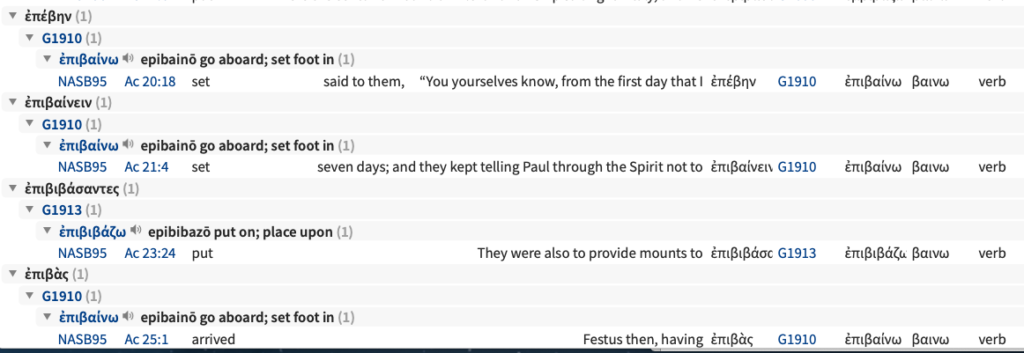

The word “covet” comes most directly from the a classic French word, coveitier, which semantic range extends from “desire” (a certain intensity of “want”) to “lust” (a burning craving). The challenge we have with languages like Latin and French (and most other languages) is that the word choice is limited in quantity so that each word tends to have a wide range of possible meanings. English has a hugely rich vocabulary, with literally hundreds of thousands of words. The Oxford English Dictionary, the gold standard of dictionaries, lists 273,000 “headwords” (essentially lemmas), some 170,000 of which are in current use. That’s an astonishing number. For comparison the vocabulary of the wonderful Koine Greek that God used to write the NT is only about 5,500. (The NT has about 155,000 words, but with a vocabulary of 5,500 different words).

What this means is that a single word in any of these non-English languages has, and has to have, a fairly wide semantic range. This makes determining the specific ‘point’ (level, intensity, aspect) at which any given word should be understood is a significant step of interpretation.

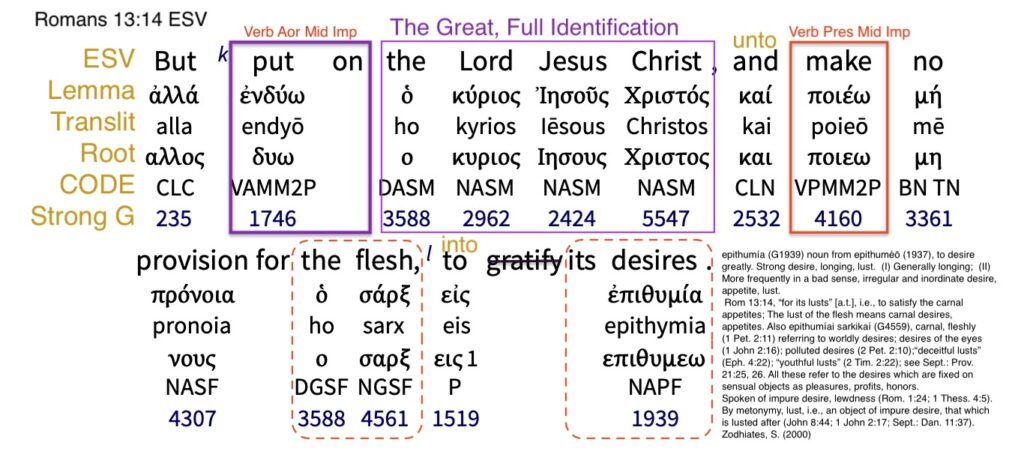

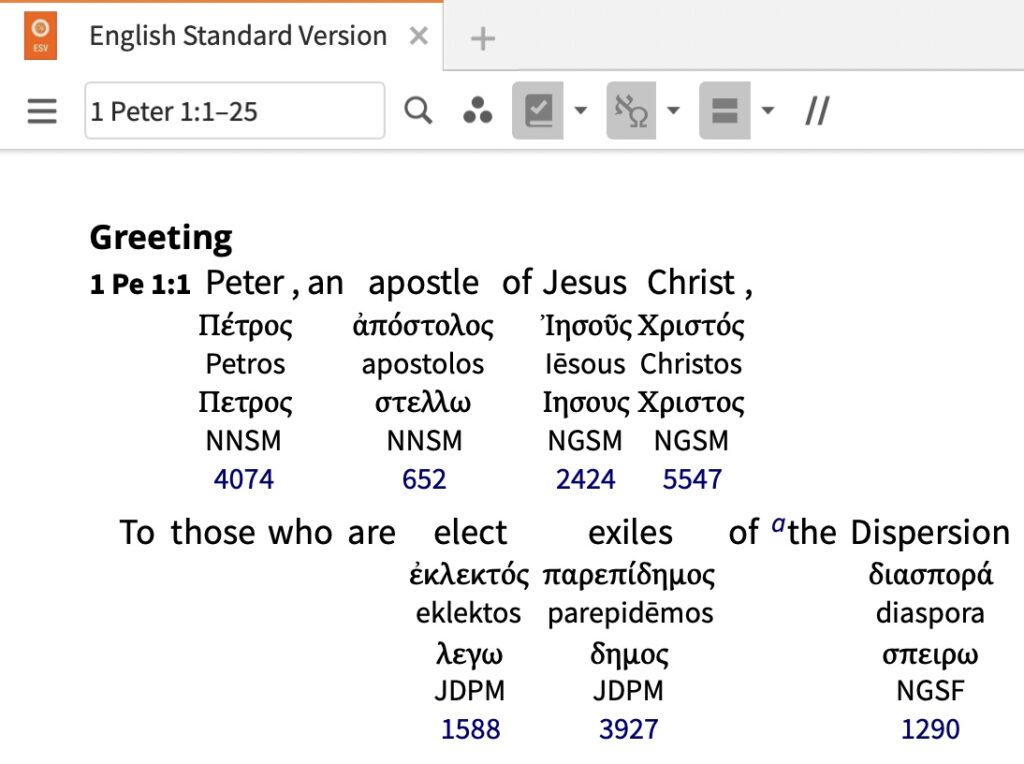

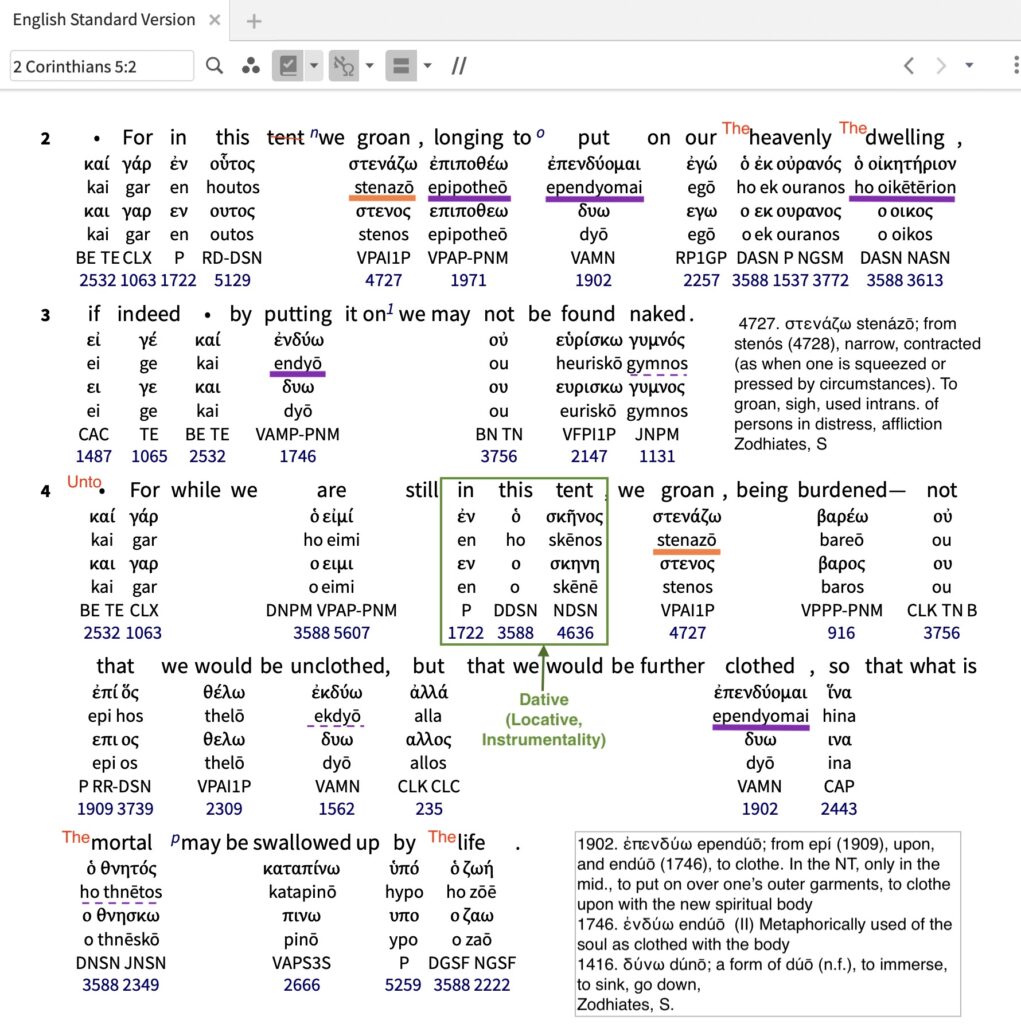

For instance, the Koine word often translated “lust” is epithumía (G1939) which semantic range includes: to desire greatly, having a strong desire, longing, lust. There’s a huge difference between “longing” and “lust.” It is the word translated as “deceits lusts” (Eph. 4:22), which in many circumstances is an oxymoron (meaning that “lusts” by their nature are “deceitful”). It is translated “lusts” in the famous passage of 1 John 2:16 as to “lusts” (or in the ESV “desires”) of the eye and of the flesh. Yet, epithumía is used by the Lord in Luke 22:15 expressing His longing for celebrating the “last supper” (the Passover supper on the night He was betrayed) with His disciples. So we have not only the question of intensity of meaning, from a little to overly much, but also to the worthiness of the object of such desire (bad vs. good, and everything in between).

It is exactly the verb form of epithumía that is used in the 10th Commandment forbidding coveting:

epithuméō (G1937) contracted epithumṓ, from epí (1909), in, and thumós(2372), the mind. To have the affections directed toward something, to lust, desire, long after. Generally (Luke 17:22; Gal. 5:17; Rev. 9:6). To desire in a good sense (Matt. 13:17; Luke 22:15; 1 Tim. 3:1; Heb. 6:11; 1 Pet. 1:12); as a result of physical needs (Luke 15:16; 16:21); in a bad sense of coveting and lusting after (Matt. 5:28; Rom. 7:7; 13:9; 1 Cor. 10:6 [cf. James 4:2; Sept.: Ex. 20:17; Deut. 5:21; 14:26; 2 Sam. 3:21; Prov. 21:26]).

Zodhiates, S. (2000)

In the Hebrew text of the OT, the word translated “covet” in the 10th Commandment is:

châmad, khaw-mad’ (H2530); a primitive root; to delight in:—beauty, greatly beloved, covet, delectable thing, (× great) delight, desire, goodly, lust, (be) pleasant (thing), precious (thing).

Brown-Driver-Briggs Lexicon

What is particularly noteworthy about such Hebrew word are the third three occurrences in the OT:

1. Gen 2:9 And out of the ground the LORD God made to spring up every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food. The tree of life was in the midst of the garden, and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

ESV, highlights mine of H2530, châmad.

2. Gen 3:6 So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate, and she also gave some to her husband who was with her, and he ate.

3. Exodus 20:17

“You shall not covet your neighbor’s house; you shall not covet your neighbor’s wife, or his male servant, or his female servant, or his ox, or his donkey, or anything that is your neighbor’s.”

So if we take “covet” as the root meaning of châmad, then as the ESV has translated it in its first use in Gen. 2:9 we can see that every tree in Eden had an appearance of attractiveness, that would draw the observer (Adam and Eve) toward it, much as our experience before a beautifully spread out fresh vegetable display in a grocery store or farmers market. God made it that way, as part of His creating delight in Creation.

Then when we see châmad characterizing Eve’s response to examining the Serpent’s temptation to partake of the forbidden tree of the knowledge of good and evil, it tells us that Eve saw something to be desired, and which desire drew her to not only take and eat crossing the boundary as to what God had forbade, and ultimately also to induce Adam to do likewise, a double evil.

Then the very next use of châmad is the 10th Commandment in Exodus 20:17 as we discussed above, and which is repeated in Deuteronomy 5:21.

There are many nuances of “covet”in English, including: pine, hanker, desire, want, crave, lust, ache (for), wish (for), aspire, envy, thirst, yearn, begrudge. We might even develop a five-star or 10-level intensity ranking that goes from, say, “slight interest” at the mildest extreme, to, at the other end, an all out overpowering craving which makes one ready to abandon all moral bounds out of an overwhelming demand to have that one particular thing we do not have. (The latter is the famed “Green Light” that drew Jay Gatsby into an entirely disordered life in pursuit of fame, and Daisy, even to his ruin and death, in the famous story by F Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby).

The Great Gatsby Story

These nuances and their respective effects upon the one having them has been the tool of many many story tellers. In recent U.S. literature a famous novel, widely read even in high schools, is The Great Gatsby. This story, written by F Scott Fitzgerald in the 1920s, a particularly interesting decade in U.S. history. The book is regarded by many to be on the short list of the greatest American novels, by some accounts the second best after James Joyce’s Ulysses.

The book has been analyzed exhaustively for nearly 100 years by scholars of literature and history, and countless student term papers, theses, and dissertations. What appears to me is that the entire context, and all the principal characters (except “Nick Carraway,” the narrator) are all given by coveting toward covetousness. A primary iconic image in the story is “the green light.” It is literally a nautical channel marker that is located at the end of the female of Jay’s primary craving, Daisy, now married but formerly in a relationship with the subject character of the novel, Jay Gatsby. Gatsby has a consuming desire (coveting) for Daisy. His house with its dock is directly across a large bay that opens into the Atlantic Ocean. So Gatsby stands at the end of his dock, at night, staring across the bay, seeing only the green light. Of course the green light is a metaphor for coveting (green is even the color associated with such feeling, as “a person green with envy”). And, so, that leads to the common question asked in discussions of the book with students: “What is your green light?” Basically, the ask is what would you be drawing to coveting such that you would commit your entire life and energy to getting even if it was unobtainable, even forbidden to you, even leading to your death? (Gatsby dies in the end–never having re-established his sought for relationship with Daisy).

It is a crazy question. But, it was what the Serpent himself presented to Eve when he propositioned Eve in Eden: the ‘hook’ that could cause Eve to not only covet the fruit of the forbidden tree, but to do so in such an urgent, consuming, secret way that she would act of such desire without consulting with Adam, let alone God Himself, but unilaterally making the biggest possible boundary-crossing available to her. The Serpent’s conclusion was that such temptation would carry over from “pleasant” to “desired” to “burning craving demanding satisfaction” because (1) it was attractive (as were the other trees), but, distinctively, (2) eating it would give Eve superior knowledge-powers even to being like the ‘gods.’ Whatever Eve understood about God, and His Creation, and the boundary against eating of such forbidden tree, she knew that she herself was not “God” nor part of ‘the gods,’ and so was missing out on something greatly to be desired, by the exaltation from being human only and not of ‘the gods.’ That desire is “coveting,” of the most-extreme character.

(What did she think being like ‘the gods’ was to become? It is conceptual madness to think that there is “The God” and to believe there can be another “God.” Was she that deeply confused, or ignorant? An alternative, which I am inclined toward, is that she believed there was a category of being where she would be ‘above’ Adam, from which she had been Created, and thus above human beings as a God-created category of being, into a super- / supra- / above human category, joining other ‘gods’ (beings of such exalted category), knowing that which “The God” had not wanted her to know. So, in such sense, she would be “like” “The God” knowing that which the category of mere humans would be excluded from knowing. And, further, that it was an inappropriate limitation “The God” had put in place perhaps in the sense of God’s selfishness (which seems to be the gist of the Serpentine’s temptation), or just an unnecessary boundary because God did not realize that His human creation category could not ‘handle’ such knowledge.)

Returning to the Serpent’s question of Eve, it was by no means a harmless question. The context of it, certainly in the Gatsby novel, is what would you so crave after that you would do anything expending any amount of time required to get something even (perhaps, especially) that which is forbidden to you? Basically, the question posed is this: What is the biggest thing you can think of that would cause to launch within you an unstoppable, irresistible craving that will in effect possess your mind, your body, your talents and interests? In short, what could be so seemingly great that you would be willing to ruin anything and everything, and people too?

We see in the OT numerous examples of coveting. Think of Cain who coveted the honor that his brother Abel received from God, and led him to kill. Then the entire line of Cain is described briefly but clearly as those seeking prideful accomplishment, including creating a city whose tower reaches to the heavens. Then we have King Saul who sought to usurp the role of the priest and later opposed even to attempt murder God’s selection for his successor, David. Then David himself with respect to Bathsheba and latter prideful numbering of Israel. Even the entire nations of the Northern and Southern Kingdoms of Israel became covetous of their respective honor. And we can point to the Apostle Paul who self-identified “covetousness” as being the source of his ultimate recognition of his being sinner. We see the Assyrian and Babylonian nations craving the imperial expansion of their domains, by conquering and enslaving other people.

And what of our pilgrimage journey home? We can be reasonably sure that we will, in our own particular context, be presented with various versions of the question “Why don’t you act upon your green light?”

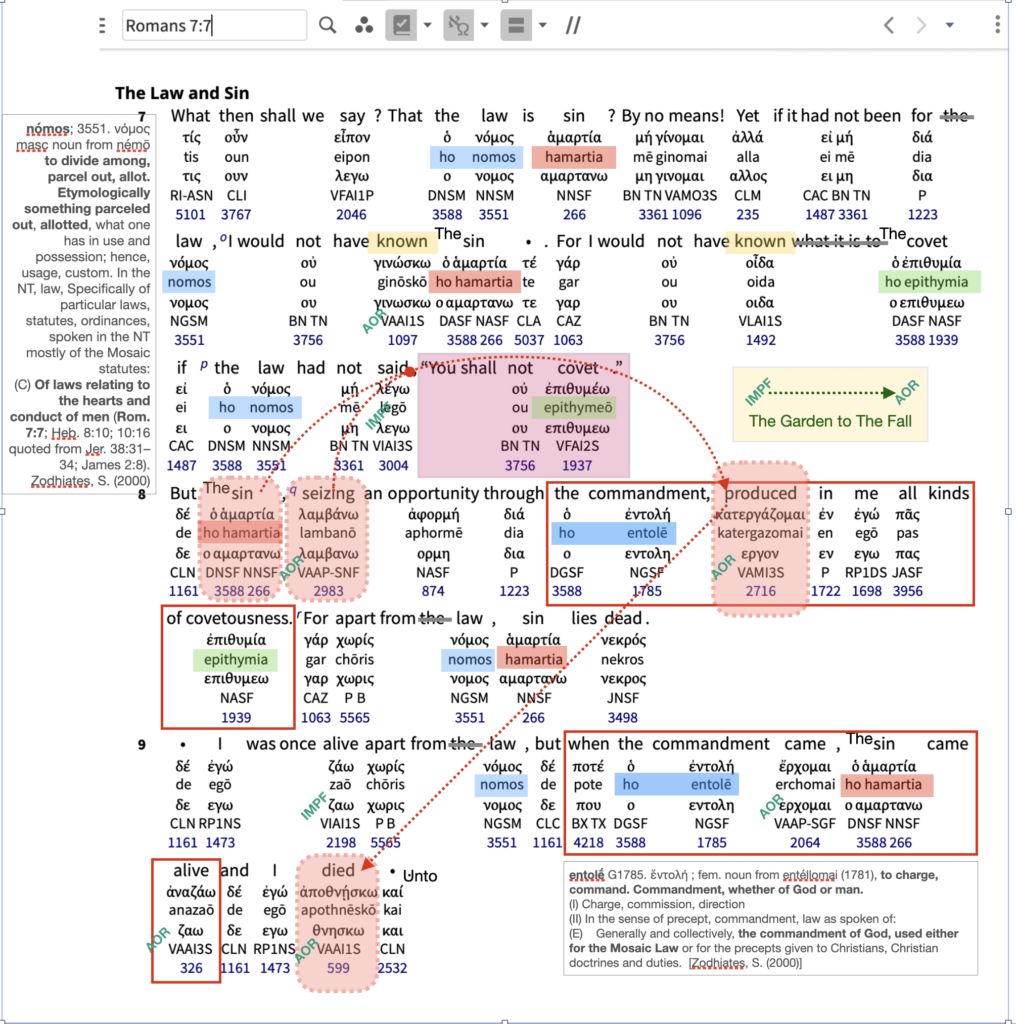

Deep Dive on Coveting in Romans 7:7-9 (ESV)

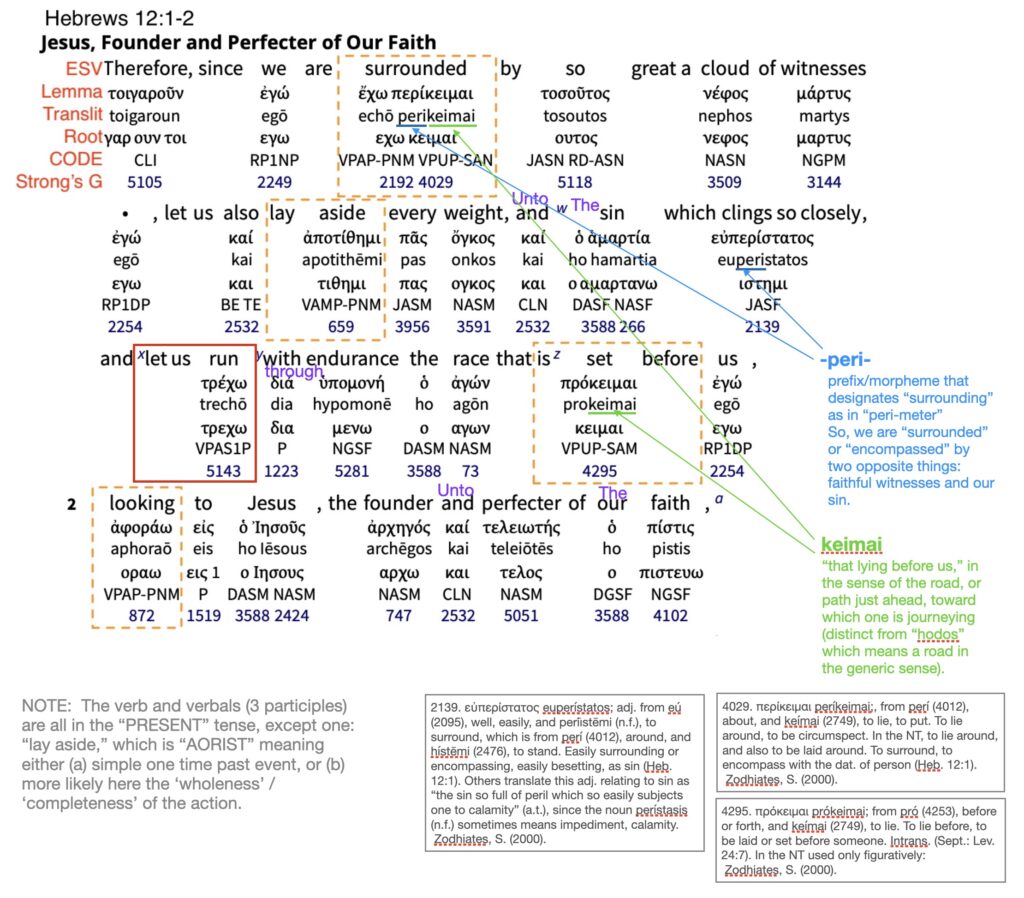

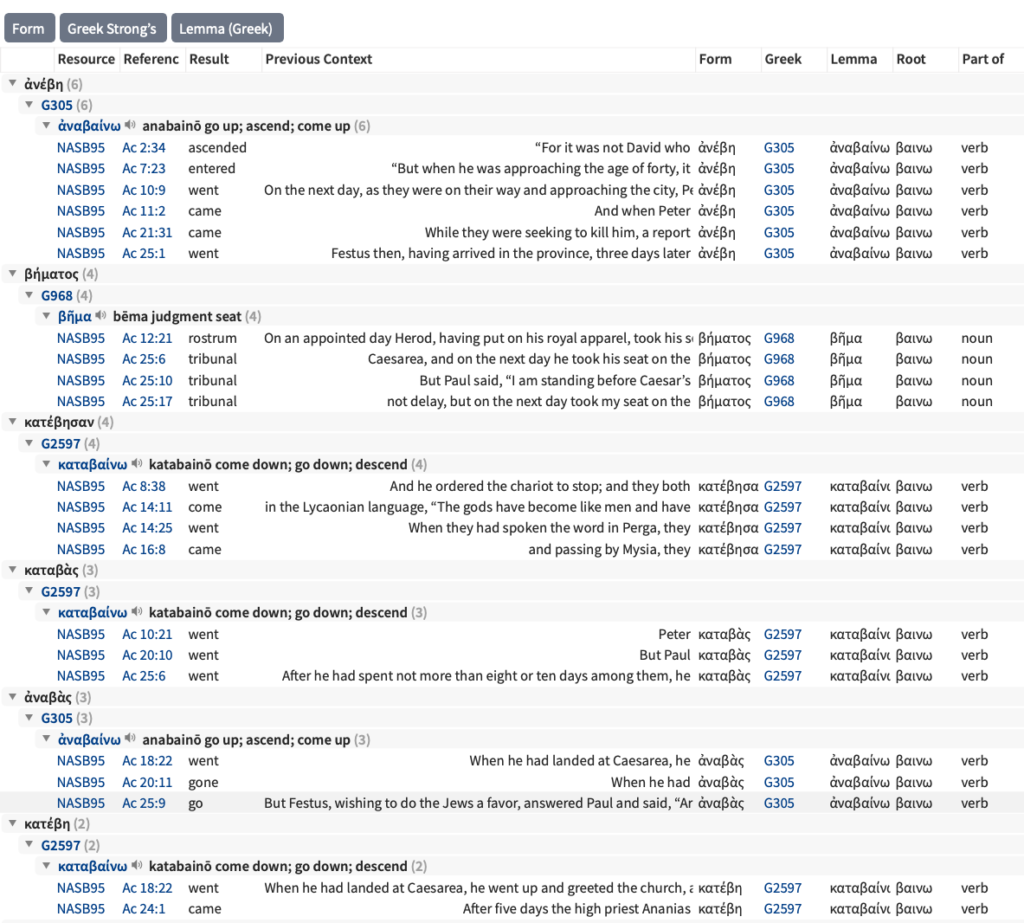

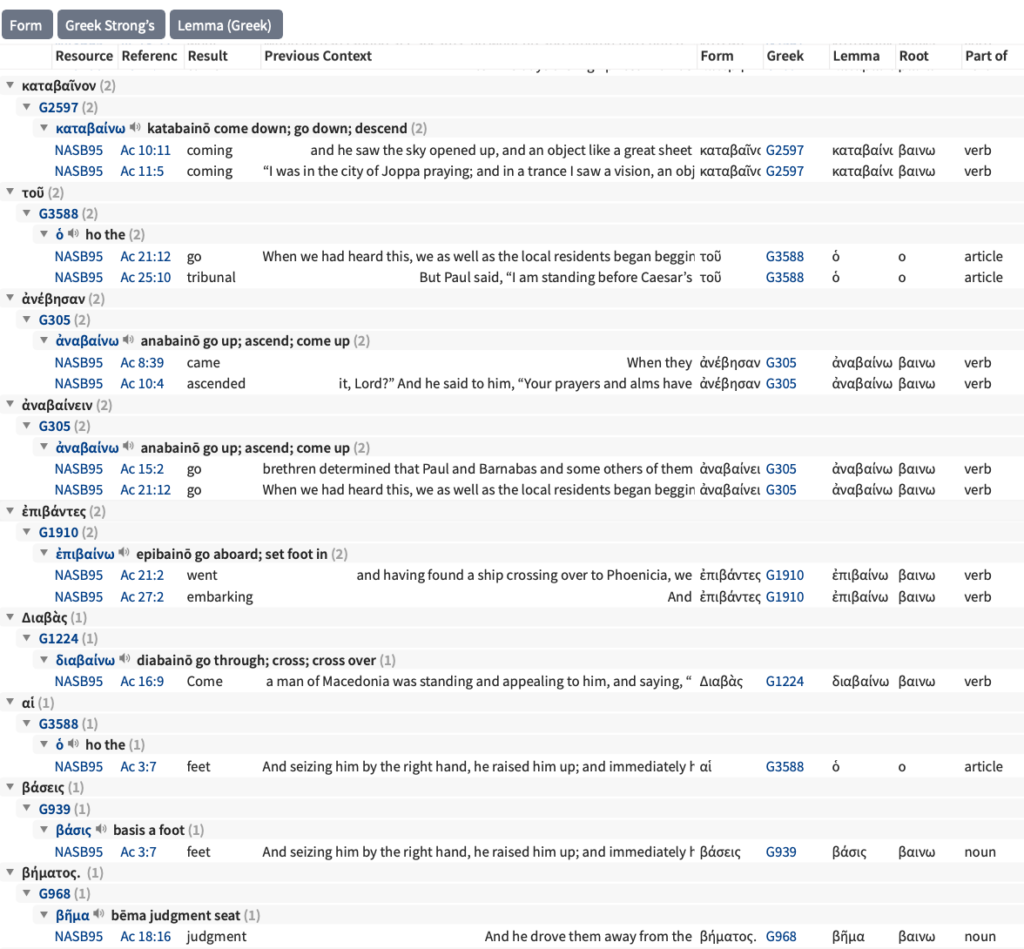

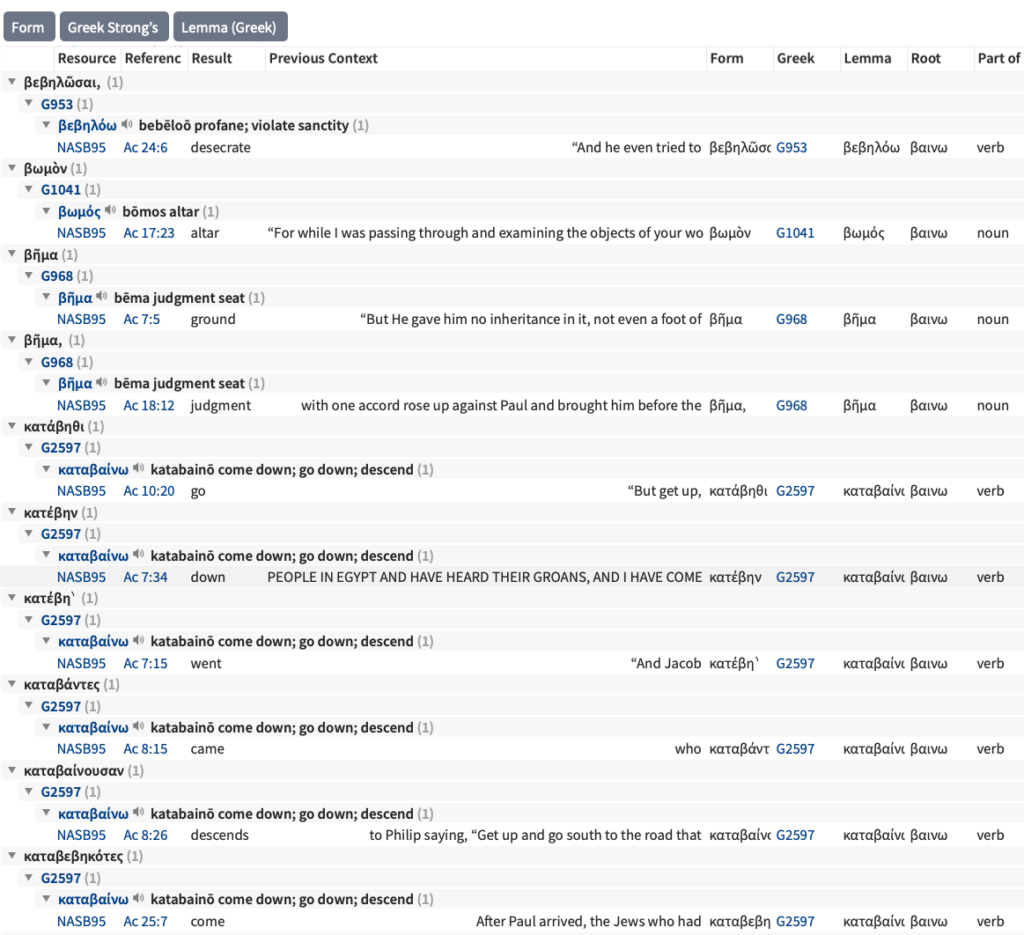

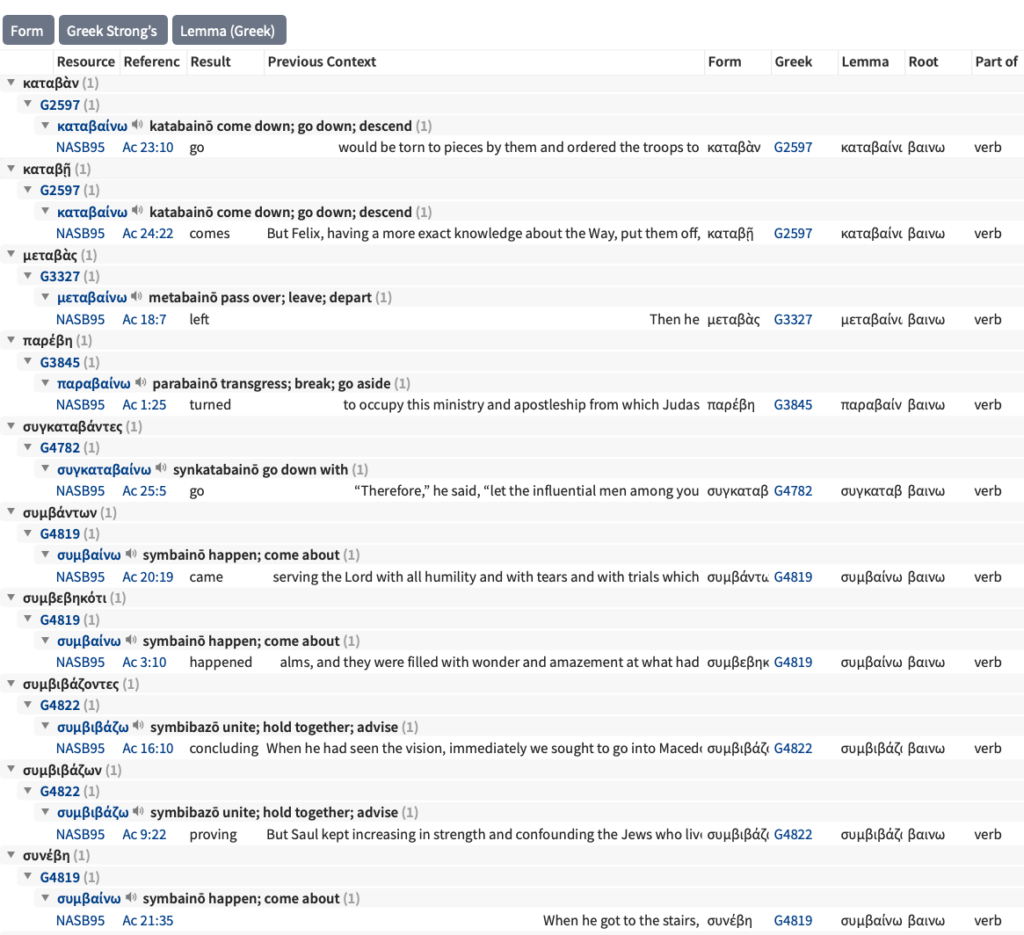

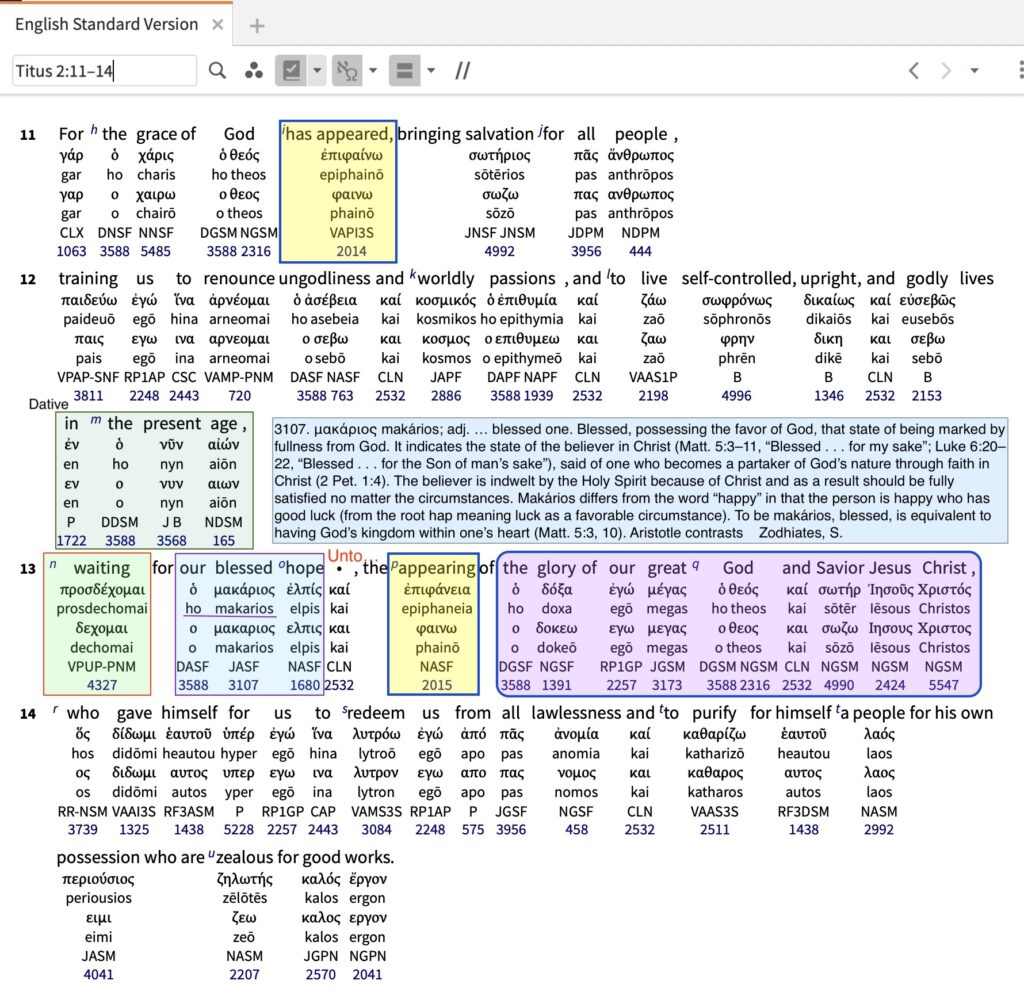

Note in the image above the following words:

- Boundary words: nomos (5x) and entole (2x)

- Passion / Lust: epithymeo (3x)

- Sin: harmatia (5x)

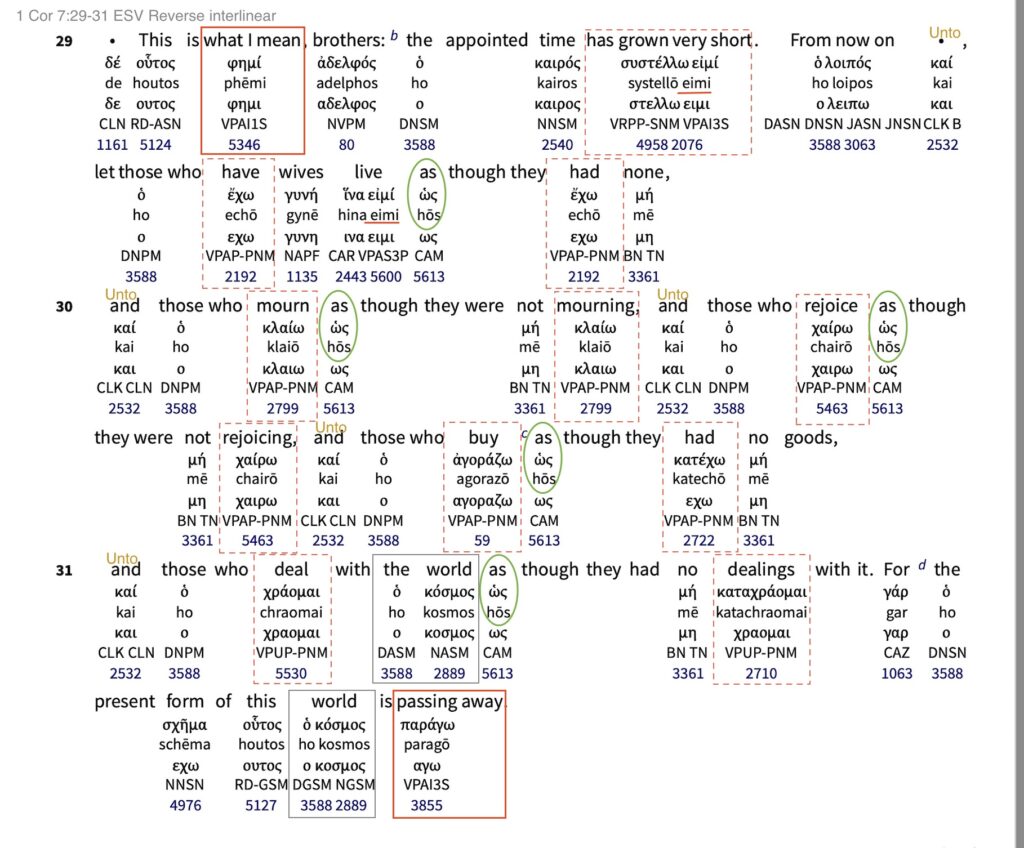

- The recreation of The Fall evidenced in the two primary verb/participle tenses (aka “aspect”), contrasting the “IMPERFECT,” continuing action in the past to the present, and “AORIST,” a one-moment in time event with its enduring consequences (can also reference a whole action).

- The distinction between articulated nouns (with a “the“) and anarthrous nouns (no “the”) is the latter tends to represent a condition of, a category of, whereas the former a specific instantiation.

The Sermon on the Mount and Coveting

The extended oration by Jesus recorded for us in Matt Ch 5-7 is known colloquially as “The Sermon on the Mount.” It is a widely known and beloved passage, that is frequently mis-taught. For our purposes here, we will consider the undergirding them of “coveting” as being one key of opening up the passage.

The Mosaic Law as it had been understood and taught in the days of the NT (and largely also in the OT), even as part of the more than 600 recognized OT commands within the Torah (the first five books of the Bible, known also as the Books of Moses) that it was deed based. There is a dictum in U.S. law known as ‘you can’t go to jail for what you’re thinking,’ meaning unless one actually does something–physical action or speech–then “The Law” has no means to reach within your head to deem you a lawbreaker.

In a similar fashion the OT Law(s) could be understood to pertain to ‘crossing some line’ from a harbored thought / passion into a physical act (including speech). So the heart, under such reasoning, with its passions, was not a lawbreaker so long as “the mind” or whatever we might attribute that which inhibits the passions within from being expressed in spacetime, is securely buttoned down, concealing the real inner condition.

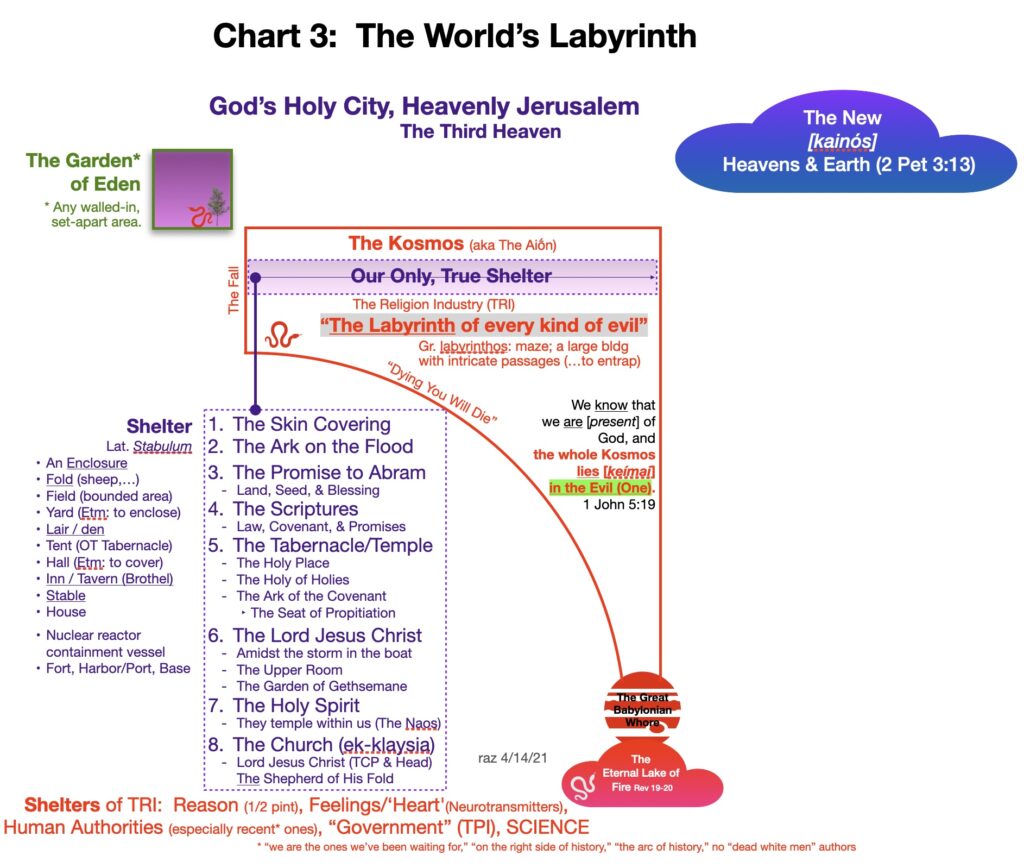

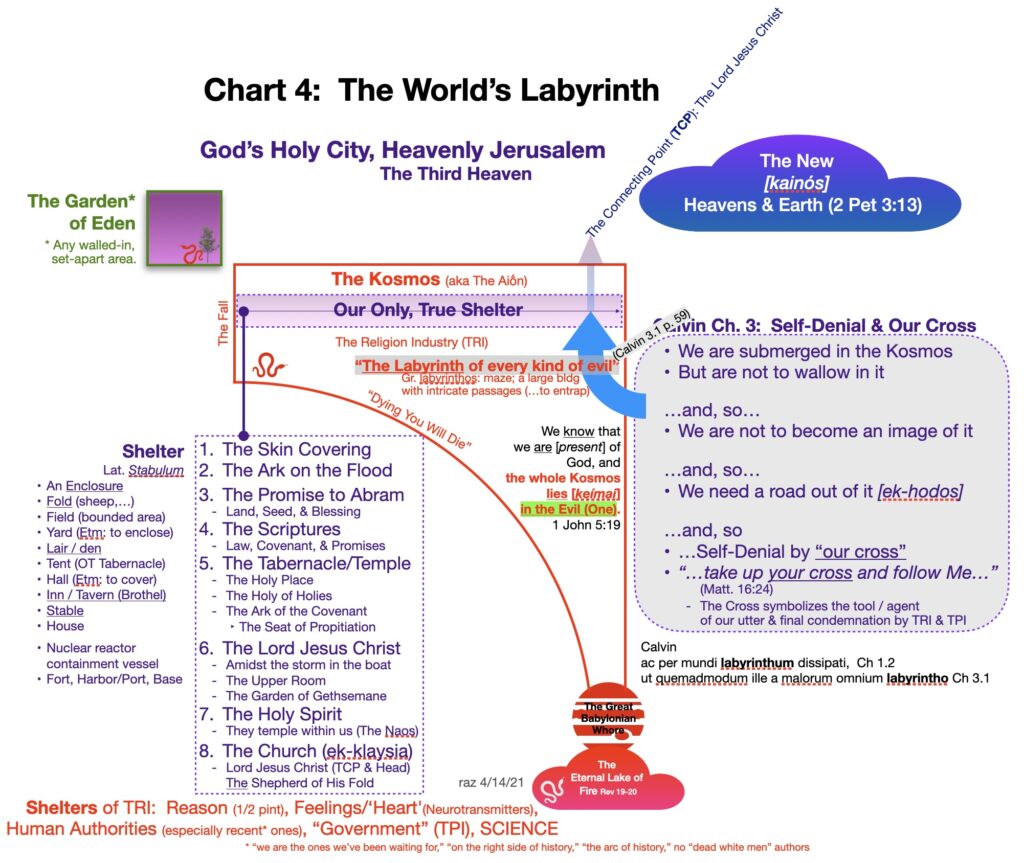

This never should have made sense in this way, but such is how The Religion Industry (TRI) tends to orient itself, and those seeking self-justification and self-redemption are inclined.

But the Sermon on the Mount exposes the previous error of such outer vs. inner distinction. Hence, the Lord begins the Sermon: “blessed are the poor…those who mourn…the meek…those who hunger and thirst for righteousness…” He is addressing those who at a fundamental level of their innermost being know, know deeply, that the externals and externalities of what had devolved into TRI (supposed followers of the Mosaic Law) at the time of the NT had not and could not cure the fallen heart, and consequent alienation from God. The underlying passion? It was “coveting,” longing for that which one did not have, was beyond a boundary of God, and toward which one’s passions where aligned and thoughts focused.

Anti-Coveting

One way to understand a thing is to grasp its opposite. What could be the opposite passion of coveting?

- Contentment

- Gratitude

- Faith in God as my Caregiver, Protector, Father

- Belief that “discipline” (including unmet desires) exists for my good

- Thankfulness

- Praise of God

- Peace (being at peace), Shalom, state of tranquility

- Un-anxiousness