This week we will continue our study of Self-Denial in connection with Bearing Our Cross, Ch. 3, Sec.s 5-6, pp. 67-71 in the D&P translation (Book 3, Chapter 8 in Beveridge’s translation)

Calvin’s heading for these two sections are as follows:

5. The cross necessary to subdue the wantonness of the flesh.

This pourtrayed by an apposite simile. Various forms of the cross.6. God permits our infirmities, and corrects past faults, that he may keep us in obedience. This confirmed by a passage from Solomon and an Apostle.

Calvin, J., & Beveridge, H. (1845). Institutes of the Christian religion (Vol. 2, p. 273). Edinburgh: The Calvin Translation Society.

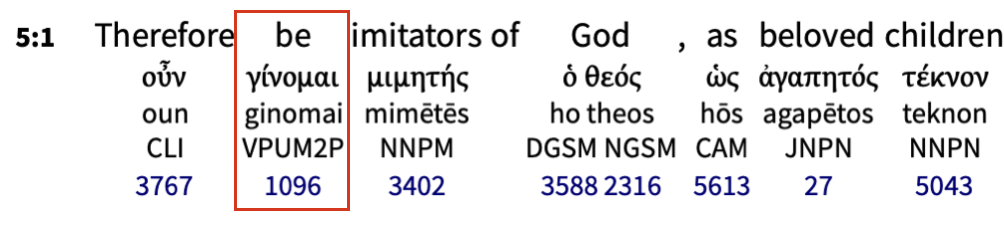

The verses cited by Calvin are given below:

Understanding the Flesh: It’s Impulses, Works, Direction

D&P’s translation of the opening sentences uses “prone” and “cast off” to characterize the basic inclination of the flesh with regard to God’s direction, which is characterized by the word “yoke.” These are important ideas, so let us consider them further.

Prone

The idea of the word “prone” is the natural inclination of something or someone. A pencil balanced vertically on it’s eraser is very prone to fall. A glass very nearly full is prone to spill. Three year olds let loose in a room full of toys and stuff are prone to create chaos. In any lawn or garden the soil is prone to yield weeds.

What about us? What are we prone to do? And, more specifically, what are we prone to do with respect to our Creator-God?

A wonderfully graphic preacher, now with the Lord, gave this illustration from life in a rural Texas farmhouse in the 1900’s. Before air conditioning, homes had open screened windows and open back doors with a screened door. Such screen doors with held in place by long, stringy springs, which rusted and weakened with age. If one just pushed open the screen door on exit, there was a unique sound of that spring stretching out to its full length as the door reversed on its hinges from its resting position, where it slowed to a stop, and from which was the dreaded sound of compression, slowly at first, and then with increasing acceleration, the screen door would slam closed, followed by a parent’s unheard cry to a kid now well down the block “close the screen door behind you!” That spring on that door was prone to slam shut, 100 percent of the time.

Another example is the needle on a compass which, by the natural law of magnetic attraction, points to magnetic north of the earth. Turn the compass, and the needle turns as well, so that it is always pointed north. That is its prone position.

Adam and His Heirs

Adam appears not to have had a prone position away from God. He was capable of sinning (and did), but in his pre-Fall state it was not a built in inclination. Post-Fall, he, and everyone since has, from first moral consciousness, primitively at first, expressed their proneness toward “self” and away from God. We may not think this is so, as part of such proneness is self-deception, and it does not look to be so with a sweet one year old child, but it is there, and ineradicable, with respect to God.

Pulling further on this important idea, let us note what the famed theologian Augustine (of Hippo, 354 – 430 A.D.) wrote on the four states of humankind, namely:

These four states, which are derived from the Scripture, correspond to the four states of man in relation to sin: 1) able to sin, able not to sin (posse peccare, posse non peccare); 2) not able not to sin (non posse non peccare); 3) able not to sin (posse non peccare); and 4) unable to sin (non posse peccare). The first state corresponds to the state of man in innocency, before the Fall; the second the state of the natural man after the Fall; the third the state of the regenerate man; and the fourth the glorified man.

https://www.monergism.com/blog/not-able-not-sin

Applying the above to our present key word “prone,” the condition of man (Adam) pre-Fall has no ‘proneness’ with respect to sin as he was both posse peccare (able, “posse,” to sin “peccare”), which he demonstrated by his willful disobedience, but he was also posse non peccare (able, “posse,” to not sin “non peccare”). What is hard for many to accept is the second condition as summarized by Augustine, namely that after the Fall neither Adam nor any descendant was by birth not able to not sin (non posse non peccare). (Jesus, of course, was born of God, though of Mary, being both truly God and truly man, and so did not inherit the curse of the Fall). “Not able to not sin” is the ultimate doom of man’s natural ‘proneness.’ The one who has been regenerated by Christ, given new life, then has by and in such new life the condition of able not to sin (posse non peccare). This is the miracle of such new birth. Yet, the curse of Adam remains within us such that such nature continues non able to not sin, hence the inner ‘war’ within us. Finally, the fourth state, of unable to sin (non posse pecarre) is the blissful, holy, secure communion with God that, like God, we will be unable to sin; however, that is yet to come. So, for now, we are stuck with two ‘pronesses,’ the first of which is our default old nature that Calvin deals with here.

An excellent pair of messages on the war of such twin inclinations–one away from God and one toward God in accordance with one’s new nature–can be heard by messages given by the late Dr. Martyn Lloyd Jones on two passages in Romans 8, here and here.

Calvin’s Latin word for such inclination, translated “prone” by D&P (and Beveridge), and wantonness by John Allen (1816 translation), is lascivia (lasciviousness), whose Latin synonyms include libido (concupiscence) and lubido (lust). Although the English cognates of these Latin words convey sexual inclinations, Calvin’s use of the word lascivia was about a direction characterized by a passion (a lascivia) away from God, even as it may be unrecognized as such, as is typically the case.

Wanton, Wantoness (alternative word for Prone)

“Wanton” as translated by John Allen is a more archaic word for this key idea of proneness, but an accurately expressive one. The below explains its origin and root meaning:

wanton (adj.) early 14c., wan-towen, “resistant to control; willful,” from Middle English privative word-forming element wan- “wanting, lacking, deficient,” … from Proto-Germanic *wano- “lacking,” from PIE *weno-, suffixed form of root *eue- “to leave, abandon, give out.” Common in Old and Middle English, still present in 18c. glossaries of Scottish and Northern English; this word is its sole modern survival.

Second element is Middle English towen, from Old English togen, past participle of teon “to train, discipline;” literally “to pull, draw,” … literally [then] “unpulled.” Especially of sexual indulgence from late 14c. Meaning “inhumane, merciless” is from 1510s.

https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=wanton

So, there are two elements of “prone” and Calvin’s lascivia: (1) it always trends toward some form of wrongness, however the form of it or the means toward it, and (2) its incapacity to self-restrain such natural, always ‘on’ impulse. There is an important distinction with regard to such incapacity. The idea is not that the impulse cannot be restrained or even extinguished with regard to some moment, or specific temptation. The issue is that there is always an impulse away from God, sometimes obvious, sometimes not, sometimes powerful, sometimes not. But even suppressed or controlled in someway, or even entire area of life, the leaning away from God never goes away. This realization was a factor in Martin Luther’s great agonies of his then monastic life as a Roman Catholic monk that he could never from his heart be pure towards being a God lover and that he actually hated God. (He later in life, teaching from the Epistle to the Romans, saw that his righteousnesses necessary came from outside of him, alien or extra nos, namely by the very Righteousness of Jesus Christ attributed by Grace to him; “extra nos,” literally “outside ourselves,” became a key distinctive of the Reformation.).

epithumía

The Bible’s Greek Koine word most closely related to “wanton” is epithumía. Below is a definition, with its Strong’s G number, and key citations from Scripture:

G1939. ἐπιθυμία epithumía; … fem. noun from epithuméō (1937),

to desire greatly. Strong desire, longing, lust.(I) Generally longing (Luke 22:15; Phil. 1:23; 1 Thess. 2:17; Rev. 18:14; Sept.: Prov. 10:24; 11:23; Dan. 9:23; 10:3, 11).

(II) More frequently in a bad sense, irregular and inordinate desire, appetite, lust.

Zodhiates, S. (2000). The complete word study dictionary: New Testament (electronic ed.). Chattanooga, TN: AMG Publishers.

(A) Generally (Mark 4:19; Rom. 6:12; 7:7, 8; 13:14, “for its lusts” [a.t.], i.e., to satisfy the carnal appetites; Col. 3:5; 1 Tim. 6:9; 2 Tim. 3:6; 4:3; Titus 3:3; James 1:14, 15; 1 Pet. 1:14; 4:2, 3; 2 Pet. 1:4; 3:3; Jude 1:16, 18). The lust of the flesh means carnal desires, appetites (Gal. 5:16, 24; Eph. 2:3; 2 Pet. 2:18; 1 John 2:16). Also epithumíai sarkikaí (4559), carnal, fleshly (1 Pet. 2:11) referring to worldly desires; desires of the eyes (1 John 2:16); polluted desires (2 Pet. 2:10); “lusts of deceit” (a.t.) means “deceitful lusts” (Eph. 4:22); “youthful lusts” (2 Tim. 2:22); see Sept.: Prov. 21:25, 26. All these refer to the desires which are fixed on sensual objects as pleasures, profits, honors.

(B) Spoken of impure desire, lewdness (Rom. 1:24; 1 Thess. 4:5).

(C) By metonymy, lust, i.e., an object of impure desire, that which is lusted after (John 8:44; 1 John 2:17; Sept.: Dan. 11:37).

As noted above, epithumía can be used in a good sense as it even describes our Lord’s desire for the Last Supper fellowship with His disciples; so “lust” is not a good universal translation as such is freighted with bad connotations. The distinction as to the merit or evil of the word is the true source of such desire and its ultimate object: it can be “good” as to both. However, if it is “bad” as to source, as in the case of our “flesh” then it is always, in the context of God’s character and law, bad in both direction (means) and end (result).

Cast Off

The yoke was an everyday work tool of agricultural economies. It was a harness that controlled the work animal(s), such as donkey, horse, or ox, so that the driver could plow the soil or pull a wagon and similar tasks. Clearly in this context the yoke is a metaphor for us accepting the purposes, and constraints, of God in life’s journey and work. Both the Beveridge and Allen translations use “throw off” as the description for the desire of our flesh with regard to such metaphorical yoke, which better captures the idea of willful rebellion. (“Cast off” feels like disconnecting a fishing boat from a pier, a more-innocuous context).

Such “throwing off” captures the idea of man’s rebellion against God. Calvin makes the key point in this section that the cross serves a purpose similar to a yoke, which imagery fits with a wooden animal yoke as use with oxen. Further, like the physical yoke on oxen, the cross cannot be thrown off, leaving the subject facing the choice of either futilely resisting or willingly accepting it’s control.

The Yoke as Medicine, as a Vaccine

Calvin cites the Old Testament example of Jeshurun (Deut. 32:15) whose personal prosperity led to his forsaking God. Calvin’s point here is that absent an unremovable yoke, namely the cross, we likewise seek our own way and comfort, sometimes even thinking such is aligned with God and His purposes. But the world’s labyrinth of epithemia’s traps us all. The yoke (cross), then, is not punishment, but more like a vaccine, or a continuous IV ‘drip’ providing life-giving medicine (D&P’s translation of Calvin here indeed uses the word “medicine”).

In the Vulgate translation of Deut. 32:15 the two key words are recalcitrō (Latin meaning “to kick” especially with the idea of despising, and the root of our word recalcitrant) and dereliquit (meaning “to abandon,” the root of our derelict).

The closing sentence of Sec. 5 in D&P is “He knows we are all diseased.” The word “diseased” is the translation of Calvin’s morbidus, which is the root of our English word morbid. Such is the condition of our fallen nature, the Bible’s use of the word “flesh,” which is (1) a universal disease, (2) fatal, and (3) yet present in living form, though not ruling, even in God’s regenerated Christian, and so, in need of ongoing intervention.

Discipline

In Sec. 6, we find the repeated use of the term “discipline” to characterize God’s work in even on our regenerated lives, clearly in the context of our being yoked. (The Allen and Beveridge translations have instead the word “chastened.” Calvin’s Latin was “corripio” which includes a wide semantic range: seize / lay hold of, carry off, censure / reproach / rebuke / chastise). So the idea is that such rebuke / chastise occurs in the context of one’s being laid hold of (‘yoked’).

Calvin cites two Scripture references on God’s discipline as below:

31 But if we judged ourselves truly, we would not be judged. 32 But when we are judged by the Lord, we are disciplined so that we may not be condemned along with the world.

1 Corinthians 11, ESV

6 For the Lord disciplines the one he loves,

Hebrew 12, ESV; vs. 6 has parallels : Psalms 94:12; 119:67, 75; Revelation 3:19

and chastises every son whom he receives.”

7 It is for discipline that you have to endure. God is treating you as sons. For what son is there whom his father does not discipline? 8 If you are left without discipline, in which all have participated, then you are illegitimate children and not sons.9 Besides this, we have had earthly fathers who disciplined us and we respected them. Shall we not much more be subject to the Father of spirits and live?

The Greek word translated by “discipline” is paideúō:

In our customary English usage, the word “discipline” conveys the idea of a punishment for misdeeds done. But the better understanding of the word is the positive, life-long learning some complex skill (which is itself sometimes termed a “discipline”) by corrective instruction, coaching, admonition, which may not have any element of punishment. Such is the idea of the Koine word in Scripture that is commonly translated to “discipline.”

G3811. παιδεύω paideúō; … from país (3816), child. Originally to bring up a child, to educate, used of activity directed toward the moral and spiritual nurture and training of the child, to influence conscious will and action. To instruct, particularly a child or youth (Acts 7:22; 22:3; 2 Tim. 2:25 [cf. Titus 2:12]); to instruct by chastisement (1 Tim. 1:20; Sept.: Ps. 2:10); to correct, chastise (Luke 23:16, 22; 1 Cor. 11:32; 2 Cor. 6:9; Heb. 12:6; Rev. 3:19 [cf. Prov. 3:12]). In a religious sense, to chastise for the purpose of educating someone to conform to divine truth (Heb. 12:7, 10; Sept.: Prov. 19:18; 29:17).

Zodhiates, S. (2000). The complete word study dictionary: New Testament (electronic ed.). Chattanooga, TN: AMG Publishers.

Paideúō occurs 13 times in the New Testament and 58 times in the Old Testament (Septuagint), so it is a common theme in Scripture. The key distinctive for understanding its relevance to us is that such chastisement / discipline / correction is the necessary element of maturation of someone (such as a child) who would not, but for such discipline, properly reach maturity.

The New Testament occurrence are given below in their respective categories of use:

We see many everyday examples of just this with one’s own children but also by what are termed ‘boot camps’ of all kinds from military contexts, to sports, to immersive trains programs in music, a particular language, etc.

A common phenomenon of young believers is, after an initial period of joy, is disappointment as circumstances and struggles of life which had been assumed to be things of the past re-emerge, or emerge for the first time or in a new way. This can seem incongruous to the promises of the Gospel. What is missing is a fuller understanding of the Christian life, its pilgrimage character, it’s recurring boot camp experiences, and the discipline (learning) ever going on under the love and yet Sovereign direction of our Father, often by means of one kind of yoke or another. Though we are called to maturity, in a sense our standing is always that of a a pais, a child, under the ever guiding Hand of God.

John Bunyan’s famed book, Pilgrim’s Progress (in continuous publication since 1678), epitomizes this in the journey of the central character, a man called Christian. He is on his life-journey from his birth city, called Destruction, to his destiny, The Celestial City. Christian is always on that journey but with numerous setbacks, asides, falls, seasons of fear and despair. Yet, he is supported again and again by Providential interventions, and companionship, and, so, he presses on, and ultimately though the final passage out of life, reaches his joyful end. And, we too, will experience in some way or form, Pilgrim’s Slough of Despond, and the valleys of Humiliation and of the Shadow of Death.

The yoke of God, and the discipline of our Heavenly Father, will get us home, all the way home, but not by the path or timing of our natural desires, or proneness.