Thy Word is a lamp to my feet and a light to my path. (Psalm 119:105)

At the links below are special topics that arise from the study of various chapters and sections in Calvin’s Little Book:

Below are links to the respective week’s study in Chapter 2 of Calvin’s Little Book on the Christian Life.

Week #4: Chapter 2 “Self-Denial,” Sec.s 1-2

Week #5: Chapter 2 “Self-Denial,” Sec. 3

Week #6: Chapter 2 “Self-Denial,” Sec.s 5-6

Week #7: Chapter 2 “Self-Denial,” Sec.s 7-8

Week #8: Chapter 2 “Self-Denial,” Sec.s 9-10

This week we’ll do a first pass through Sections 1-3 of Calvin’s Chapter 4 (corresponding to Beveridge Book 3, Chapter 9).

Calvin has much to say about the World’s evils, our attraction to it, and our proper response away from it toward God. I have collected these observations on a special topic page, here:

Calvin’s headings for this Chapter 4, and for Sections 1-3 (from Beveridge’s translation) are as below:

Of Meditating on the Future Life

The three divisions of this chapter,—

I. The principal use of the cross is,

that it in various ways accustoms us to despise the present,

and excites us to aspire to the future life,

Sec. 1, 2. II. In withdrawing from the present life we must neither shun it nor feel hatred for it; but desiring the future life, gladly quit the present at the command of our sovereign Master,

Sec. 3, 4. III. Our infirmity in dreading death described.

The correction and safe remedy, Sec. 6.Sections

1. The design of God in afflicting his people.

To accustom us to despise the present life. Our infatuated love of it.

Afflictions employed as the cure.

To lead us to aspire to heaven.2. Excessive love of the present life prevents us from duly aspiring to the other.

Hence the disadvantages of prosperity. Blindness of the human judgment.

Our philosophising on the vanity of life only of momentary influence.

The necessity of the cross.3. The present life an evidence of the divine favour to his people;

Calvin, J., & Beveridge, H. (1845). Institutes of the Christian religion (Vol. 2, p. 285). Edinburgh: The Calvin Translation Society.

and, therefore, not to be detested. On the contrary, should call forth thanksgiving.

The crown of victory in heaven after the contest on earth.

The verses Calvin cites supporting these sections included in the D&P translation are as below:

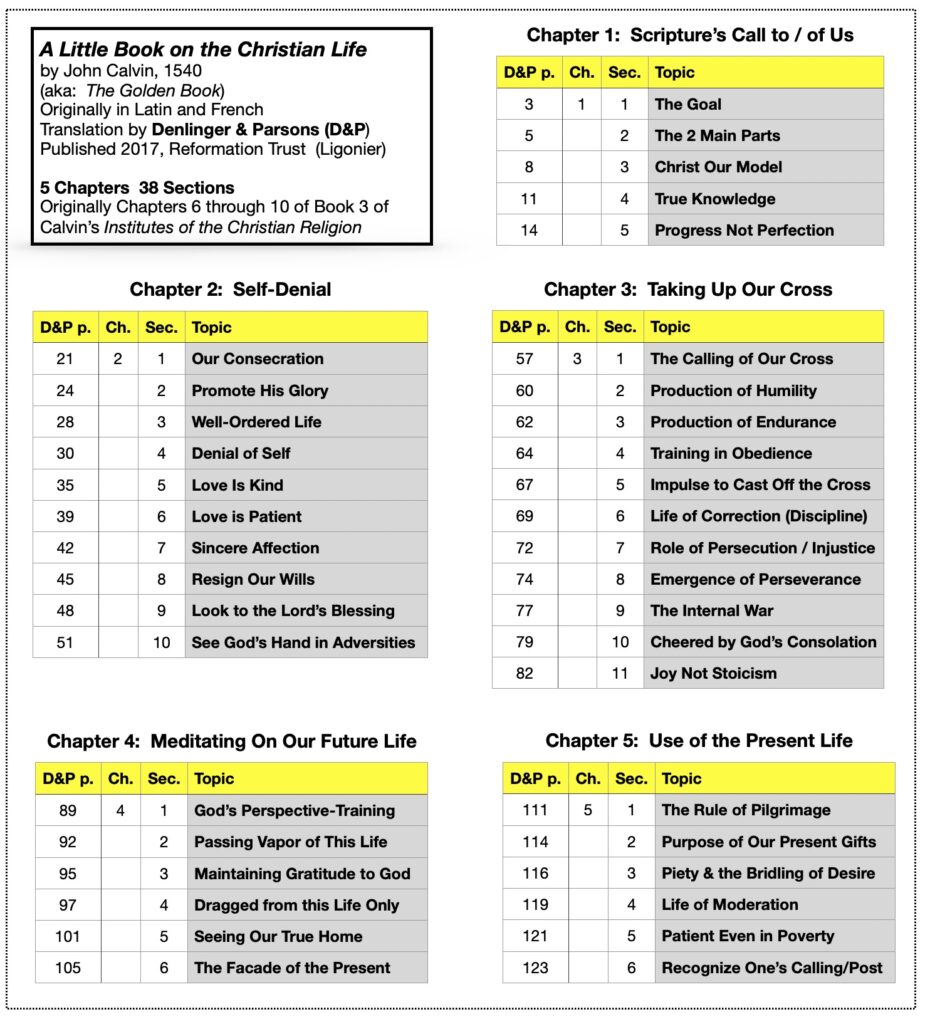

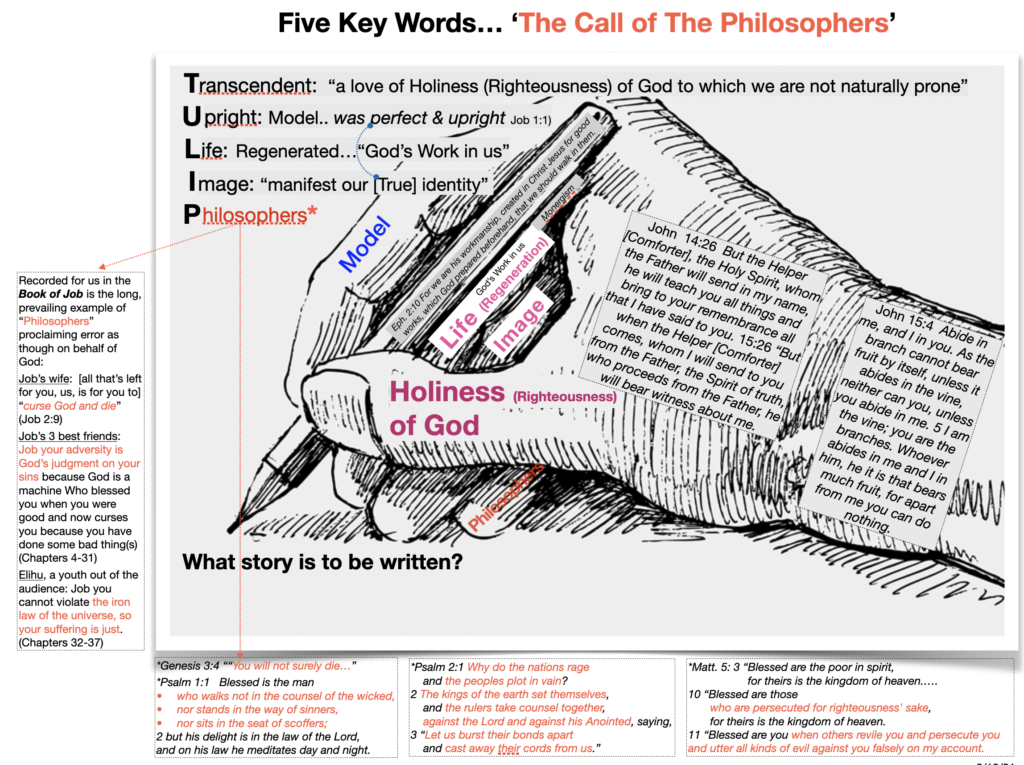

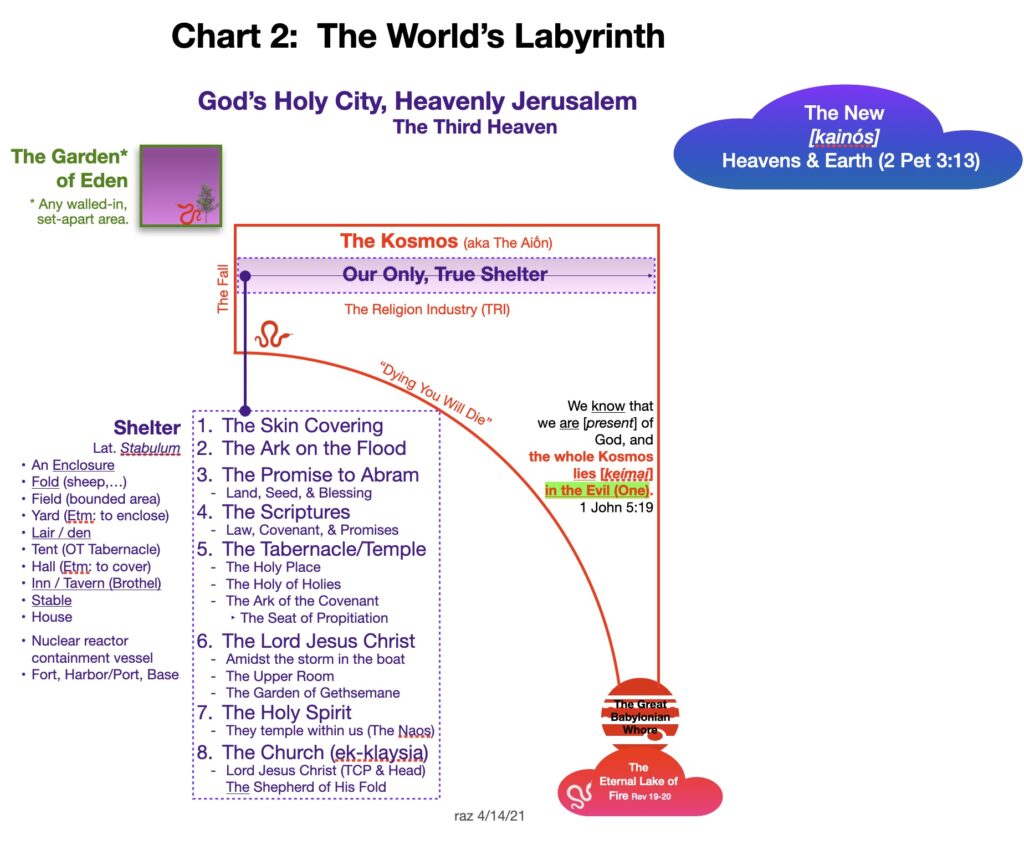

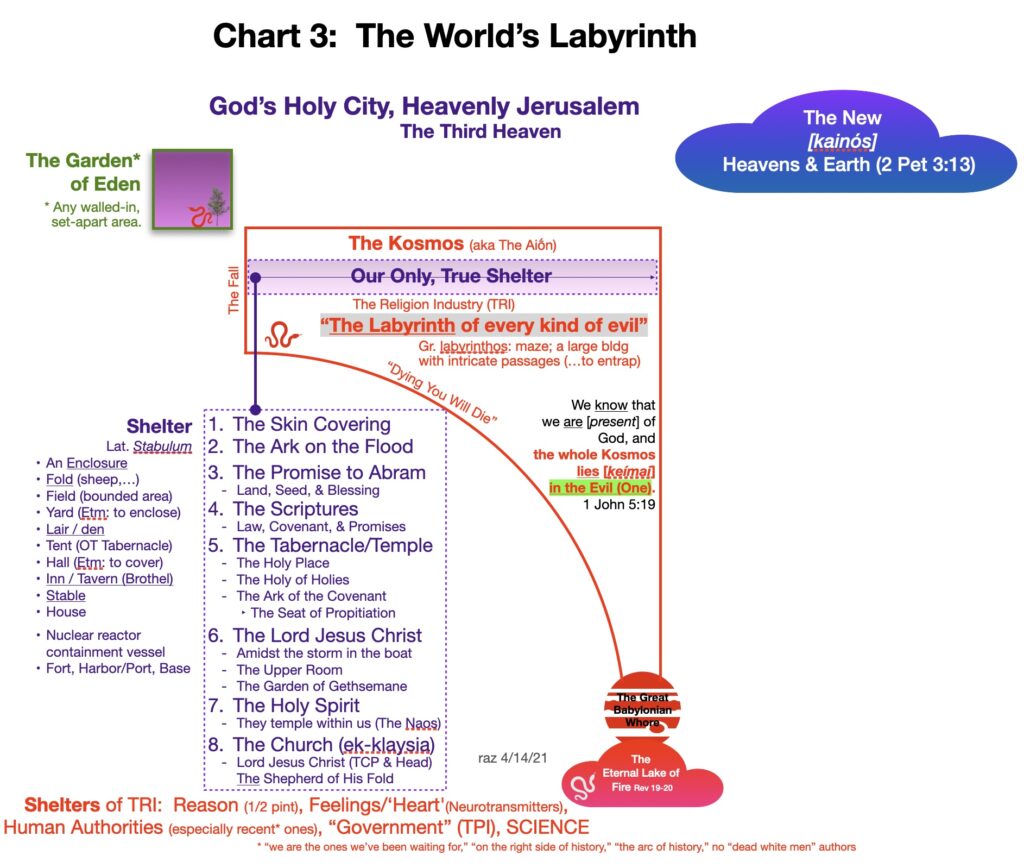

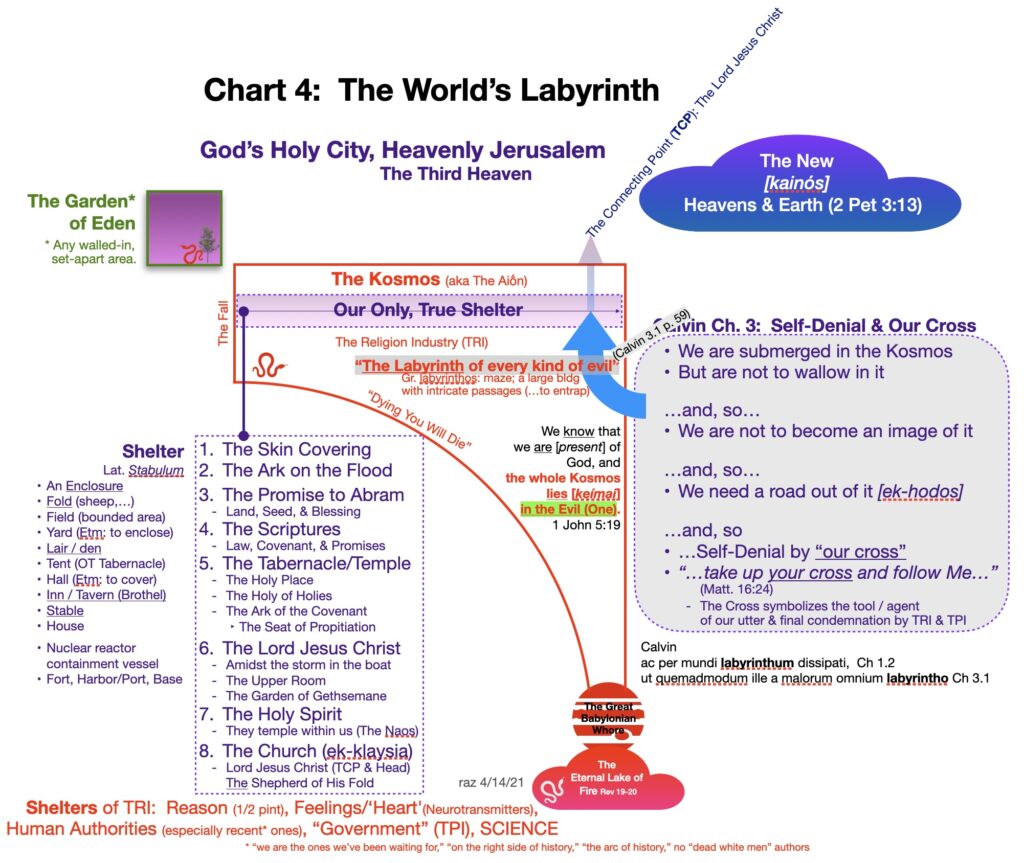

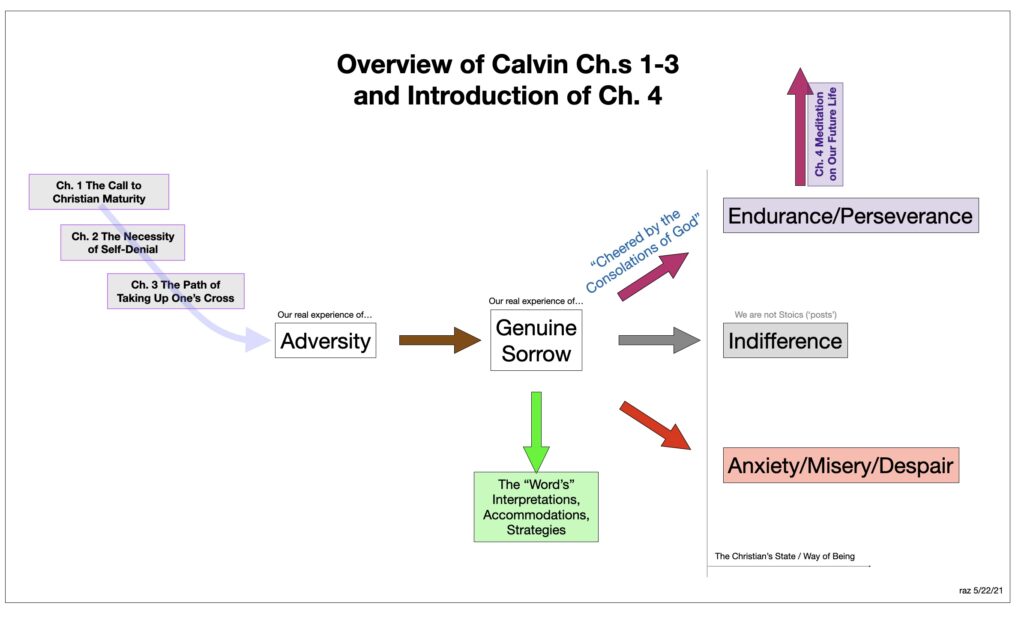

A graphic that will assist this overview of what we’ve covered and the chapter ahead is given below:

It might be imagined that the call of God coupled with the Providence and Love of His Character makes for smooth living here and now, every day, in every way. The Scriptures, and clearly Calvin in his Ch.s 2 and particularly 3, say otherwise. Exactly opposite otherwise.

Consider just this sample of descriptors Calvin used for the adversities of life:

(And all of the above is from Calvin’s first Section of Ch 4).

What then of the adversity that enters our life, again, especially in the context of our having taken up the Cross? Clearly Calvin, and Scripture especially considered comprehensively, says yes indeed we do experience genuine sorrow.

In the below pdf are some additional verses from the Bible on sorrow. Though far from a complete list it gives a clear indication that sorrow is an experience God’s children undergo, some more than others, and differently than others.

As shown in the above chart, I am distinguishing between “genuine sorrow” and a bad place to live and be, namely the very unholy (and unbiblical) ‘trinity’ of anxiety, misery, and despair. But, still, is there genuine sorrow in a Christian life particularly one which is living seeking the Lord’s Will? The answer is yes. Consider:

SORROW Emotional, mental, or physical pain or stress. Hebrew does not have a general word for sorrow. Rather it uses about 15 different words to express the different dimensions of sorrow. Some speak to emotional pain (Ps. 13:2). Trouble and sorrow were not meant to be part of the human experience. Humanity’s sin brought sorrow to them (Gen. 3:16–19). Sometimes God was seen as chastising His people for their sin (Amos 4:6–12). To remove sorrow, the prophets urged repentance that led to obedience (Joel 2:12–13; Hos. 6:6).

The Greek word for sorrow is usually lupe. It means “grief, sorrow, pain of mind or spirit, affliction.” Paul distinguished between godly and worldly sorrow (2 Cor. 7:8–11). Sorrow can lead a person to a deeper faith in God; or it can cause a person to live with regret, centered on the experience that caused the sorrow. Jesus gave believers words of hope to overcome trouble, distress, and sorrow: “I have told you these things so that in Me you may have peace. In the world you have suffering. Be courageous! I have conquered the world” (John 16:33 HCSB).

Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary

GRIEF AND MOURNING Practices and emotions associated with the experience of the death of a loved one or of another catastrophe or tragedy. When death is mentioned in the Bible, frequently it relates to the experience of the bereaved, who always respond immediately, outwardly, and without reserve. So we are told of the mourning of Abraham for Sarah (Gen. 23:2). Jacob mourned for Joseph, thinking he was dead: “Then Jacob tore his clothes, put sackcloth around his waist, and mourned for his son many days. All his sons and daughters tried to comfort him, but he refused to be comforted. ‘No,’ he said. ‘I will go down to Sheol to my son, mourning.’ And his father wept for him” (Gen. 37:34–35 HCSB). The Egyptians mourned for Jacob 70 days (Gen. 50:3). Leaders were mourned, often for 30 days: Aaron (Num. 20:29), Moses (Deut. 34:8), and Samuel (1 Sam. 25:1). David led the people as they mourned Abner (2 Sam. 3:31–32).

Mary and Martha wept over their brother Lazarus (John 11:31). After Jesus watched Mary and her friends weeping, we are told, “Jesus wept” (John 11:35). Weeping was then, as now, the primary indication of grief. Tears are repeatedly mentioned (Pss. 42:3; 56:8). The loud lamentation (wail) was also a feature of mourning, as the prophet who cried, “Alas! My brother!” (1 Kings 13:30; cp. Exod. 12:30; Jer. 22:18; Mark 5:38).

Sometimes they tore either their inner or outer garment (Gen. 37:29, 34; Job 1:20; 2:12). They might refrain from washing and other normal activities (2 Sam. 14:2), and they often put on sackcloth: “David then instructed … ‘Tear your clothes, put on sackcloth, and mourn over Abner.’ ” (2 Sam. 3:31 HCSB; Isa. 22:12; Matt. 11:21). Sackcloth was a dark material made from camel or goat hair (Rev. 6:12) and used for making grain bags (Gen. 42:25). It might be worn instead of or perhaps under other garments tied around the waist outside the tunic (Gen. 37:34; Jon. 3:6) or in some cases sat or lain upon (2 Sam. 21:10). The women wore black or somber material: “Pretend to be in mourning: dress in mourning clothes, and don’t anoint yourself with oil. Act like a woman who has been mourning for the dead for many years” (2 Sam. 14:2 HCSB). Mourners also covered their heads, “[David’s] head was covered, and he was walking barefoot. All the people with him, without exception, covered their heads and went up, weeping as they ascended” (2 Sam. 15:30 HCSB). Mourners would typically sit barefoot on the ground with their hands on their heads (Mic. 1:8; 2 Sam. 12:20; 13:19; Ezek. 24:17) and smear their heads or bodies with dust or ashes (Josh. 7:6; Jer. 6:26; Lam. 2:10; Ezek. 27:30; Esther 4:1). They might even cut their hair, beard, or skin (Jer. 16:6; 41:5; Mic. 1:16), though disfiguring the body in this way was forbidden since it was a pagan practice (Lev. 19:27–28; 21:5; Deut. 14:1). Fasting was sometimes involved, usually only during the day (2 Sam. 1:12; 3:35), typically for seven days (Gen. 50:10; 1 Sam. 31:13). Food, however, was brought by friends since it could not be prepared in a house rendered unclean by the presence of the dead (Jer. 16:7).

Not only did the actual relatives mourn, but they might hire professional mourners (Eccles. 12:5; Amos 5:16). Reference to “the mourning women” in Jer. 9:17 suggests that there were certain techniques that these women practiced. Jesus went to Jairus’s house to heal his daughter and “saw the flute players and a crowd lamenting loudly” (Matt. 9:23 HCSB).

Drakeford, J. W., & Clendenen, E. R. (2003). Grief and Mourning. In C. Brand, C. Draper, A. England, S. Bond, & T. C. Butler (Eds.), Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary (pp. 690–691). Nashville, TN: Holman Bible Publishers.

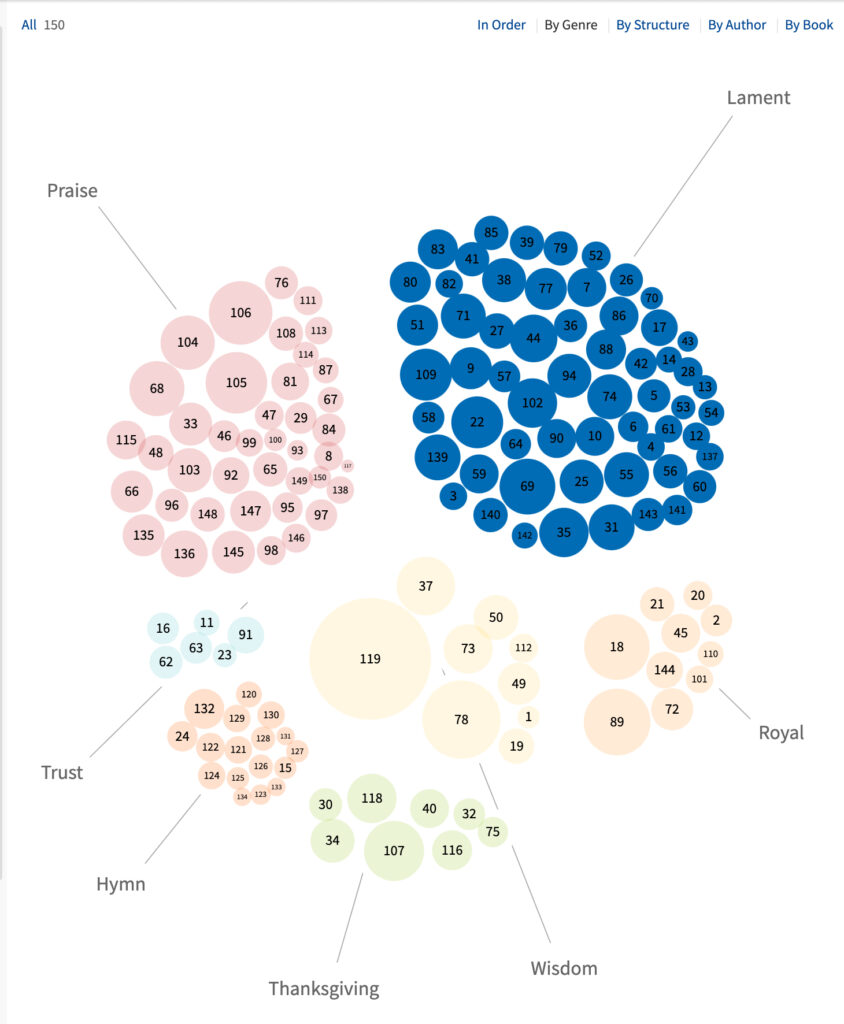

Consider the Book of Psalms. One useful perspective is to group the 150 individual Psalms by genre such as the seven categories shown in the graphic below (taken from a useful feature in Logos Software). Of these seven, the genre of “lament psalms” is clearly the largest (59 are considered to be in this category) and the subset of these termed “grief-lament” includes 43 psalms. The Psalms typically considered to be “encouragement psalms” number just 10, but eight of these 10 belong to the genre of “lament psalms,” showing that true encouragement commonly, and most reasonably, occurs in the context of lament or more specifically “grief” (sorrow):

Finally, consider the Greek word commonly translated “sorrow” in the New Testament. The graphic below (from Logos Software) show four forms of the root word “lúpē” that occurs 19 times, and a 20th word “odúnē.”

Further insight on the Greek word lúpē is given below. Note the many New Testament synonyms for this word indicating prevalence of the experience in multifaceted forms:

G3077. λύπη lúpē; gen. lúpēs, fem. noun. Grief, sorrow (Luke 22:45; John 16:6, 20–22; Rom. 9:2; 2 Cor. 2:1, 3, 7; 7:10; 9:7; Phil. 2:27; Heb. 12:11; Sept.: Gen. 42:38; Jon. 4:1). Metonymically for cause of grief, grievance, trouble (1 Pet. 2:19; Sept.: Prov. 31:6).

Deriv.: alupóteros (253), less sorrowful; lupéō (3076), to make sorry; perílupos (4036), surround with grief.

Syn.: katḗpheia (2726), a downcast look expressive of sorrow; odúnē (3601), pain, distress, sorrow; ōdín (5604), a birth pang, travail; pénthos (3997), mourning; stenochōría (4730), anguish, distress; thrḗnos (2355), wailing, lamentation; kópos (2873), weariness; sunochḗ (4928), anxiety, distress; básanos (931), torture, torment; pónos (4192), pain; tarachḗ (5016), disturbance, trouble; thlípsis (2347), tribulation, affliction; thórubos (2351), disturbance.

Ant.: chará (5479), joy; agallíasis (20), exultation, exuberant joy; euphrosúnē (2167), gladness.

Zodhiates, S. (2000). The complete word study dictionary: New Testament (electronic ed.). Chattanooga, TN: AMG Publishers.

One cause of sorrow is that of being excluded, even exiled. In our judicial system we have a constitutional prohibition against “cruel and unusual punishment.” The origin of such prohibition goes back to the use of torture in many forms as part of the penal system of the nations of Europe from which our constitution evolved.

But one form of penal punishment that is allowed is “solitary,” or “the hole,” whereby a prisoner is put in isolation for a time, perhaps a long time. In other contexts such isolation would be considered a positive: being put in a hotel room with a co-worker is less preferable to having one’s own room. How, then is isolation, separation, an added punishment for a prisoner?

The answer seems to be that we are innately social beings, though not necessarily 24 hours a day, or in all places or on everyday. But being ‘cut out’ of contact, excluded from belonging, can be a source of great sorrow. Such occurs even with children and teens as to their social groups, or the infamous ‘cool kids table’ at the high school lunch room. But it continues through all of life. And in these years of 2020-21 under pandemic restrictions of travel and association many have experienced despair in such isolation, despite all manner of online information resources and even people-‘connection.’

If we’d like to be able to be part of whatever group, club, society, what is required of us? What’s the admittance ‘fee?’ Depending on the group, such ‘fee’ can be so large as to be unachievable in our circumstance (which is likely why it exists). In many cases, the ‘fee’ is some version of conformity. We, body and perspective / values, need ‘to fit’ with the group.

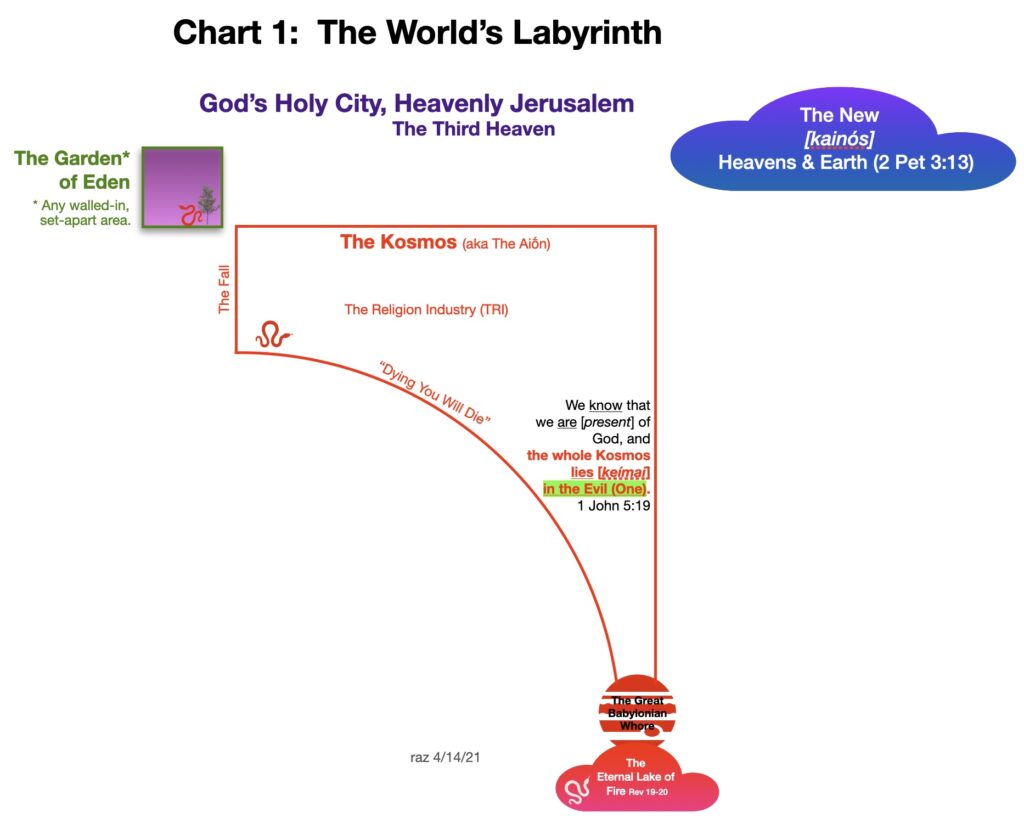

Following the path to Christian Maturity, a title sometimes used of Calvin’s Little Book, and is the theme of its First Chapter, necessarily leads to perspectives, ideas, values that “the world” (Kosmos) will emphatically deem to be incompatible with it. The Scriptures make clear, there is darkness and there is light and the darkness hates the light, and flees from the light, because its deeds are evil. The likely favorite verse of Christians is John 3:16; but that verse heads an important paragraph as below:

16 “For God so loved the world,[i] that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life.17 For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him.18 Whoever believes in him is not condemned, but whoever does not believe is condemned already, because he has not believed in the name of the only Son of God. 19 And this is the judgment: the light has come into the world, and people loved the darkness rather than the light because their works were evil. 20 For everyone who does wicked things hates the light and does not come to the light, lest his works should be exposed. 21 But whoever does what is true comes to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that his works have been carried out in God.”

Gospel of John, Chapter 3, ESV

So, choosing, especially loving, such light excludes a person from the darkness-loving world (Kosmos). What can make this a cause fo Christian sorrow is that many of such groups are not evil in the sense of fleshy wickedness, but are aligned opposed to God to follow the wills of their self. We, too, full of “self” as well, can easily be drawn to such groups, as Lot was when he chose to leave Abram, as was Lot’s wife after she came to experience to the prosperity of the river valley civilization as it was then in the lower Jordan River valley.

Being excluded may cause us sorrow, but such should be so to protect us from a worse adversity, turning from God to adopt the perspectives and values of the world’s system.

Charles Spurgeon was one of the great preachers of the 19th Century. Fourteen of his sermons dealt with the subject of “genuine sorrow.” A pdf of his sermon on “Sanctified Sorrow” is directly below. It has a the traditional three-part format, where each corresponds to the major phases of “life,” from new creation to physical death.

Another example Spurgeon message, this one “Sorrow and Sorrow” is below:

The context of Spurgeon’s message “Sorrow and Sorrow” is sin leading to true, Godly sorrow and repentance and to true joy. So, such sorrow is of a different character than the subject of Calvin’s Chapter 2 and especially Chapter 3, which derives from adversity, but not adversity that derives from sin. However, I’ve included it here because Spurgeon, as is his characteristic, makes many insightful observations. Some nuggets from the above message are below:

There are twin truths “that lie side by side, like the metals [rails] on which the railway carriages ride. These are, in the context of coming to Christ: (1) the emphasis on the need for repentance, true and deep, as proclaimed by “those experimental [experience-driving] preachers” intending to produce “very sturdy Christians” by “deep ploughing” (into one’s sin and hopeless condition) before “they begin to sow the good seed of the kingdom;” and (2) the simple proclamation of the Gospel message “Believe, and live,” emphasizing the sowing, sometimes “all sowing and no ploughing.”

How to reconcile the two? There is nothing to be reconciled, as they are both true and taught in Scripture as Luther meets Calvin as did Paul meets James. (In our contemporary culture the term “easy believism” has arisen and been applied to the preachers of the second ‘rail’ only).

Man’s fallen condition, which is never fully grasped apart from the revelation of God is without “life” but “the charnel-house of man’s corruption” from which “you shall never be able to discern any remedy for a sin-sick soul.” A “charnel-house” is a perfect description as it was the place in which unclaimed skeletons were piled, such as might be found when digging up a foundation; churches of that day would have such an out-building known by that term. It came to symbolize the ultimate sorrow of irreversible death. It is worth reading this message just for the paragraph containing such imagery.

What makes certain “sorrow”…”Godly sorrow?” Spurgeon puts it this way: “”the godly sorrow [is that] which worth repentance to salvation,” that is, “it is an agent employed in producing repentance, but it is not itself repentance.” Thus, “in the world, a great deal of sorrow on account of sin which is certainly not repentance, and never leads to it,” because such sorrow is of sin’s consequences–be they psychic, social, criminal or eternal–as without such consequences the person exhibiting this form of sorrow would gladly return to their sin.

Another mistake made by many–that this sorrow for sin only happens, once–as a sort of squall, or hurricane….” Spurgeon freely confesses “that I have a very much greater sorrow for sin today than I had when I came to the Savior…” as “sorrow for sin is a perpetual rain, a sweet, soft shower which, to a truly gracious man, lasts all his life long.”Spurgeon notes another common misunderstanding “that sorrow for sin is a miserable feeling.” Rather, he says, “there is a sweet sorrow, a healthy sorrow.” Spurgeon exhorts “come, brother, come sister, you and I cannot afford to live at a distance from Christ. We cannot afford to live in a state of misery,” that which results from not using “sorrow” to bring us closer to Christ.

The seriousness of sin as an evil directly against God is what maturity brings to awareness. We are attuned to wrongs we do against another person or against the society of people (i.e, a crime), but the world does not see evil acts against the will of God as being as that serious, “but,” Spurgeon says, “the essential thing is to be sorry because the evil is a wrong done to God.” “…when a man is really awakened, he sees the gravamen of the offense.” “Gravamen” is another word worth looking up: it comes from the Latin gravere, meaning to weigh down, from which we get our scientific term “gravity,” and was used of a legal complaint, or grievance, that was a basis of a legal action (lawsuit), an offense deserving of penalty of judgment.

Spurgeon expounds further on repentance as it means a fundamental change of mind “about everything, and especially about sin. A man is so sorry for having done wrong that he thinks differently now of all wrong-doing. He thinks differently of his entire life…to live just the opposite way to that in which has formerly lived.”

Further, Spurgeon notes that repentance causes us to expand our concept of sin and evil, introducing the phrase “purlieus of iniquity.” “Purlieus” is no longer a common term but it is worth understanding its meaning and application. In England from the middle ages (and likely even earlier), down to Spurgeon’s time (1834-1892), had certain very notable laws about the “forest” land, certain of which related to the rights of nobility as to hunting and so forth. The question then naturally follows as to exactly where does “the forest” end? So the word “purlieus” developed into an important legal term meaning the area adjacent to “the forest,” that may or may not have isolated trees, shrubs, and such, was part of “the forest.” Spurgeon’s use is insightful because our human tendency is to defined sin as narrowly as possible, in part to shrink it, and perhaps in part because we’d like to get close enough to it to peer over, as it were, the boundary and see the goings on without feeling that we are doing the evil. “Purlieus of iniquity” helps us think of the evil of the close association with that which is more clearly demarcated as “evil.”

As a final Spurgeon term of art is his phrase “the smart of sin.” “Smart” here has nothing to do with with “wise,” but the sting, the immediate sharp pain. The root of this word means quick, active, so we apply it to quick learners. But sin, and the guilt and sorrow from it, can have that kind of effect, an immediacy of experience, and a painful one.

The above are my notations of Spurgeon’s direct phrases shown in quotations, all based upon the publication of a sermon Spurgeon gave on Sunday Evening, July 31, 1881. How wonderful it would have been to sat there and heard his powerful, unamplified voice fill the Metropolitan Tabernacle in Newington (area now known as Elephant and Castle), England. For the history of the Tabernacle see here:

The universality of the experience of adversity and genuine sorrow has led to many, multivariate accommodations, strategies, helps, explanations, ‘solutions.’ Examples? The entire history of man starting with Adam & Eve’s hiding with fig leaves give us countless examples, which emerge and re-emerge to this day, everywhere, and in every context.

Let us very briefly consider some major categories. Our purpose here is certainly not to make the case for any of these, though some more than others contain a certain space-time ‘wisdom.’ But they are all woefully inadequate to the Call, Self-Denial, and the Cross. Further, they all express in some essential way the will of man, independent of God, to make his way, as did Cain and his descendants in building their city whose pinnacle can reach to the heavens in some sense of saying to God Himself: “So there! We’ve done this without and despite You!”

This is the old ‘standby’ for suppressing unhappiness while giving a temporary illusion of happiness, contentment. A close relative is “entertainment” in whatever form: sports, movies, TV, the internet ‘vortex’ (social media, YouTube, blogs).

The goal of the producers / providers of such is: (1) make themselves money, preferably a lot of it, by (2) by providing in trade one or two hours, perhaps more, during which a viewer can lose their ever-present consciousness of self-existence. Otherwise, as the saying goes, wherever you go…there you are. It is really hard for you to escape you. And when, as it does happen, it is for just a short period with the common result that you feel worse after than at the start, similar to sitting and eating a large tub of ice cream (another version of Drugs, Sex, Rock n’ Roll).

Yes there exists “The Happiness Project” (researchers at University College, London), and numerous hyped books with ‘expert’ authors hyped continuously. Most of these are anecdotal, personal experience, or hypothesized keys–formulas even–to attaining a state of happiness.

Examples? Go outside. Sleep longer, better. Use stronger interior lighting, especially in dark climates or seasons. Exercise, even just walk a little. Call a friend. Love yourself, as in treat yourself as your best friend. Treat carbs as poison. Or, treat carbs as your friend (because, it is noted, that Jesus did not feed the 5,000 with fish and a side salad). Start a diary / journal to record your daily feelings and experiences. Play a musical instrument, sing a song, especially a happy one in a major key (C Major is always good; but stay away from B Flat). Put post note affirmations on your mirrors. Clean your room, make your bed. Be a learner, especially a lifelong learner. Stop being mean to people. But don’t be a pushover. Be generous. But, also look our for yourself. Do stretches, faithfully each day. Do daily tapping with both index fingers on your temple area. Whistle (but not with a “whistle”). Floss (don’t know the connection with happiness, but lots of people say this is important).

And, so forth. Fill up some 50,000 words of text about whatever comes into your head–and the previous paragraph is a good start–self-publish on Amazon, and, so, you have been self-made into an authority, literally (author-ity). Work social media. Post and promote regulary. Start a podcast. Maybe Oprah will invite you on to her show. Put a small assortment of Christian words and phrases, but be careful because you don’t want to lose the secular audience whose antenna are tuned to ‘hate speech,’ and you can sweep in a religious community of followers.

So, there is no reason to read any already published books or web searches. Just make up your own idealized version, and ‘go with it’ (but…it will be a road to nowhere, an aporia, but it may take a few years, decades even, to realize it).

Focus on the duty at hand, the way forward. Trudging forward, no matter what, is the way forward and keeps you from noticing that you are trudging.

Want nothing. Craving is the curse. Crave not, and you won’t be pained by having nothing. Nothing is good (it’s all ‘up’ from there).

Sickness is an illusion. It’s not real. So if you think you are sick, or getting so, the problem is you are thinking.

Such “rules” are common propositions with the learning of new skills. Consider the simple example of learning to use a windsurfing board (a surf board with a sail on it). There are many challenges involved, beginning with just climbing up out of deep water onto the board without sliding over back into the deep. Then there’s the challenge of just standing and balancing. Then there’s raising the mast, and so on and so forth. Typical instruction is given using the rule of “100,” namely that there’s no “failure” (metaphor here for “sorrow”) because what is required for windsurf capability is 100 tries without success. So upon the first fall, which customarily occurs on the first try in the first half-minute, there’s a declaration of accomplishment because it is now “one down, 99 to go.”

Teachers and professors use similar “rules” to encourage new learners, such as a first course in a new language such as Spanish or Greek. Students are reminded that each semester of 15 weeks of three-classes a week, 45 nominal in class-contact hours, will be supplement by double that number with homework, making for 135 hours, after which time the student will be speak, read, write at a certain basic level. Then, in following up in a four year academic major would result in about 1,000 hours and a significant level of competency.

One author has written a book on the “rule” of 10,000 hours as being a common numeric standard for a high level of “mastery” in many different areas of life.

In all such frameworks, the guidance customarily given is there is no need for “genuine sorrow,” as it’s simply a matter of ‘reps’ (repetitions), earnestly done, with of course some innate level of capability / compatibility, that leads to achievement.

Coaches of individual sports like golf or tennis, and group sports like football, employe similar strategies to the above numeric rules. But further, they stress the absolute importance of looking forward to the next play or event, so as not to be captive to the adversity of a prior event leading to the related feeling of sorrow, grief, anxiety, fear. As they say, the game must go on, and so must every one seeking, at the end, to be declared the winner. So, for a golfer, for example, you cannot ‘carry’ a prior double boggy (a very bad score for a professional golfer on any given hole) with you on future holes and, so, affecting the individual golf swings that must now be made.

Just singing happy songs, with physical movement, in a community of happy people, or those compelled to fake it, makes one, after a time, as happy as the songs and the community itself. It can be similar to attending a Garth Brooks concert, but with needing an often hard-to-get ticket.

A system of “religion” with its vestments, drama, even smells, all within the aura of a dramatic enclosure of height, span, and beauty can make one feel connected to something very big, and secure. TRI can be one’s protector in an uncertain world.

The system of community agreements that bind people and groups together can promise another kind of security, and even justice through the power of law and enforcement, including compulsory tribute paid to the common treasury.

The Call of Ch. 1 from which we began this study in Calvin’s Little Book anticipated and included the central concept that our experience is to be a state of being, way of doing (and going) that reflects the character foundation of endurance / perseverance. (As discussed in previous Week’s, Calvin frequently uses the Latin word from which we get “moderation,” but its original meaning was to react alternatively to our natural human, space-time, impulse to flee from the experience, or to deny it, or strategize against it).

Now in this beginning of Chapter 4 in Calvin’s Little Book we will see a key to our endurance / perseverance that goes ever beyond the simple teaching of the Scriptures to be so, namely: there is something beyond our present space-time experience that is so so close that there are those moments in prayer and meditation with God when it, and He, seems more real than any human experience we’ve ever had.

Think of a womb-baby. He, or she, is just an inch or so from a world-reality incomprehensibly different from their present, though real, experience of “life.” Yet, in a very shot time, and with some reluctance, that little guy is thrust into the outer real life for which he has been conceived and formed. In just a few minutes the traverse occurs, often in travail (for both mom, even dad, and the little guy too).

1. Whatever be the kind of tribulation with which we are afflicted, we should always consider the end of it to be, that we may be trained to despise the present, and thereby stimulated to aspire to the future life. For since God well knows how strongly we are inclined by nature to a slavish love of this world, in order to prevent us from clinging too strongly to it, he employs the fittest reason for calling us back, and shaking off our lethargy.

Calvin, J., & Beveridge, H. (1845). Institutes of the Christian religion (Vol. 2, p. 285). Edinburgh: The Calvin Translation Society.

From this [the ever present evils of our space-time] we conclude, that all we have to seek or hope for here is contest; that when we think of the crown we must raise our eyes to heaven. For we must hold, that our mind never rises seriously to desire and aspire after the future, until it has learned to despise the present life.

IBID.

The above conclusion by Calvin is direct, even harsh: (1) this present life, properly faced while on the journey to Christian maturity is and will always be “contest” (discussed further below), and (2) for our eyes (and heart) to be properly directed to our future beyond and after space-time, we must learn to “despise” this life. This is the absolute opposite of “Your Best Life Now,” and every other version of the prosperity Gospel, and of the labyrinth of the world (Kosmos) seeking to entrap us (thus the “contest”).

Beveridge’s translation gives us “contest,” whereas D&P “trouble.” “Contest” does not work for our age as it calls up the idea of a sports game. “Trouble” doesn’t exactly work either as that encompasses flat tires, dropped phone calls, and the like.

A better word, in my judgment is “conflict.” Conflict captures the essential idea that the Light of the Gospel, the Bible as a whole, is, when properly understood and proclaimed, in a state of conflict with any worldview that is man-centered or, even worse, centered on a god of man’s conception.

Calvin used in his Latin original the word certāmen (-inis, noun, from the Lat. verb certo). The Latin word is used of a contest, a competition. But the idea I think Calvin was expressing, also encompassed by certamen is dispute, dissension (not in the sense of argumentation but as the expression of a foundational difference in life-view). Another suitable translation would be “dispute.” All of such ideas convey the always-existing opposition of ideas.

Philosophers frequently deal with such oppositions. One well-known and still prevalent perspective was formulated (or approximately so) by Hegel as: First, thesis; then antithesis; finally synthesis, known by Hegelian Dialectics.

One simple perspective on this view is that sustained conflict is a naturally unstable existence. Inevitably, something just gives way. So in the rub between an existing world view (the “thesis”) and an alternative, conflicting world view (the “antithesis’) is a form of resolution, accommodation (the “synthesis”). Which, according to the theory only leads to a new thesis from which there will inevitably arise a new antithesis and thus synthesis and so forth. The optimistic form of the dialect is that such process produces better world views, better worlds, better humans and their conditions for living. The 20th Century is 100 years of evidence challenging such optimism, and the 21st continues to do so.

However, in Biblical terms, the conflict, the certamen, began before space-time, with the Fall of Satan, began at the very onset of space-time, with the Fall of Man (Edenic Fall), continued to and through Jesus Christ presenting Himself as Messiah, and has continued every since, to this day, and will until the time and occasion of Revelation 22. If there is any “synthesis,” some attempt at peaceful coexistence, then either God has changed His mind about Evil, or the Devil has changed his mind about God. I’ll let the reader assess the possibility of such occurring.

The Beveridge translation has it that God has called us to “despise” this present life. D&P instead translates the idea as “scorn.” Calvin’s Latin was contemptu, which nominally can be translated by either despise or scorn, and is clearly the source of our word “contempt.”

The etymology of “contempt” is helpful to aid our understanding:

late 14c., “open disregard or disobedience” (of authority, the law, etc.); general sense of “act of despising, scorn for what is mean, vile, or worthless” is from c. 1400; from Old French contempt, contemps, and directly Latin contemptus “scorn,” from past participle of contemnere “to scorn, despise,” from assimilated form of com-, here probably an intensive prefix (see com-), + *temnere “to slight, scorn, despise,” which is of uncertain origin.

…Phrase contempt of court “open disregard or disrespect for the rules, orders, or process of judicial authority” is attested by 1719, but the idea is in the earliest uses of contempt.

https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=contempt

The proper idea of “contempt”–and scorn or despise–in our Biblical context is not that of being a superior looking down on worthless, stupid, evil inferiors, especially the people ‘on the other side.’ First, we need to recognize that there is one that is on the other side, the Evil One himself, and his devils, and spawn, which is does not extend to all the humans who at any given time may express their opposition to the Light of the Gospel, as did Saul before he became Paul, as did the many who cried “Crucify Him!” at the trial by Pilate. There is an intractable opposition that will never relent, never be transformed, and will always oppose even to torment and physical death (but no further, and not even to that stage without Providential Permission). There is no “meeting of the minds” possible in such case, without abandoning the essence of the Gospel, and of Christ Himself.

However, we note that the Lord Himself called down from the Cross of utter condemnation by the Evil One asking God the Father, a communication within the Trinity, that Christ was Himself offering Himself as the means of the Father’s forgiveness of those who do not know what they are doing. In the same way, Steven the Disciple, the first martyr, asked God not to hold accountable the men in religious ignorance who at that very moment were stoning him to death solely for his proclamation of the Gospel, to which they were then mortally opposed.

So, perhaps a better translation for despise / scorn would be an artful way of saying we are in a state of unending mortal combat, about the most important issues of reality, the Character of God, and of man, the only means of restoration / regeneration, and eternal destinies post the end of Space-Time. And there is no peace to be had in this life, though we will hear of many Neville Chamberlin’s proposing such (Chamberlin was the British Prime Minister who claimed he had achieve “peace in our time” because he had the signature of Adolph Hitler on a piece of paper he was waving around after having landed in England after such negotiations).

Charles Spurgeon spoke repeatedly about heaven, and our next life, some 37 distinct sermons by some count. Below is a Spurgeon illustration of what it will be like leaving earth for heaven:

The Earth Clings to Us Job 1:20–22

What is the use of all that clogs us here? A man of large possessions reminds me of my experience when I have gone to see a friend in the country and he has taken me across a plowed field, and I have had two heavy burdens of earth, one on each foot, as I have plodded on. The earth has clung to me and made it hard walking.

It is just so with this world. Its good things hamper us, clog us, cling to us, like thick clay. But when we get these hampering things removed, we take comfort in the thought, “We shall soon return to the earth from which we came.”

We know that it is not mere returning to earth, for we possess a life that is immortal. We are looking forward to spending it in the true land that flows with milk and honey, where, like Daniel, we shall stand in our lot at the end of the days. Therefore, we feel not only resigned to return to the womb of mother earth, but sometimes we even long for the time of our return to come.

Spurgeon, C. (2017). 300 Sermon Illustrations from Charles Spurgeon. (E. Ritzema & L. Smoyer, Eds.). Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press.

Spurgeon, C. (2017). 300 Sermon Illustrations from Charles Spurgeon. (E. Ritzema & L. Smoyer, Eds.). Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press.

This week we will complete Sec. 9 of Ch 3, and begin Sec.s 10-11, the final sections of Ch 3 on Self-Denial and the Cross.

Calvin’s own heading for these final three Sections (as translated by Beveridge) are as follows:

9. A description of this conflict. Opposed to the vanity of the Stoics.

Illustrated by the authority and example of Christ.10. Proved by the testimony and uniform experience of the elect.

Also by the special example of the Apostle Peter.

The nature of the patience required of us.11. Distinction between the patience of Christians and philosophers.

Calvin, J., & Beveridge, H. (1845). Institutes of the Christian religion (Vol. 2, pp. 273–274). Edinburgh: The Calvin Translation Society.

The latter pretend a necessity which cannot be resisted.

The former hold forth the justice of God and his care of our safety.

A full exposition of this difference.

The Scriptures cited by Calvin in these Sections are as follows:

As discussed in Week #12, the latin Word D&P has translated as “endurance” is “moderatio.” (And from such word, Beveridge gives us the translation “moderation”). However, “moderation” conveys a different mean in our language today than was meant by Calvin and taught in the Scriptures. The root idea of “moderation” is “self control” and the obvious connection is to “self-denial,” the subject of Calvin’s Ch 2 and 3, and here specifically with respect to what can be perceived as unjust adversity.

At some point we have recognized, or if not yet we need to recognize, that the God to which we are called is sovereignly in control of all events, and can bestow riches and honors beyond measure, like the seven great grain harvests of Egypt in that first period of plenty (and the seven barren ones that followed…both came from the Providential Hand of God for His greater purpose than just food). And, we know, or have to know, that we are beloved by God beyond all measure even to the clearest of all possible evidences, namely the death of Jesus Christ in our place, taking on our the full judgment and wrath of the Father against sin, eternally and irreversibly so, and thus imputing to us the very righteousness of Christ Himself, the Eternal God-Son.

We then might logically anticipate the ‘garden’ like blessing of prosperity and ease of Adam (and Eve) himself would be our life experience. Or, at worst, we would have a life without major sorrows or difficulty. But, as the Scriptures make clear, and is Calvin’s recurring focus in these twin chapters (2 and 3), we should anticipate that our experience in the spacetime, here and now, will be filled with all manner of adversity. (A simple exercise is to take a red pencil and underline every word that Calvin uses that speaks in some form of such adversity as to be expected as our experience). How can this make sense, be just? We can reasonably expect that not only the opposite should be true for us but all this foretold adversity should, as we think of these matters, be the full and sole experience being God’s enemies not His children.

So, when our experience conflicts with our reason (as just given above), we have a troubled mind. Has this all been false? Is God getting even with us for our imperfections (and worse)? Is God really not Sovereign, powerful? Is He not loving? Is He so transcendent from us and even all of spacetime, like an artist who painted a great work, or turned on some incomprehensibly massive machine, and left for other business intending to return at some future eon of time? How does our experiences and particularly those worse of the worse ones that we learn of that affect fellow believers in Christ cohere with the doctrines of Scripture?

Likely the oldest book in the Bible, and even in humankind, is the Book of Job. Job’s story is very familiar to almost everyone. What is not fully appreciated is that even at the conclusion of the book, where God Himself enters the story with a very long narrative, there is no final explanation of why this all had to happen to Job.

One of the central teachings of Job, then, is that God is indeed Sovereign, but not accountable to explain all (or any) of His purposes, even to the one most-directly affected, Job himself. One thing Job learned is that for some things it not his place to ask of God an explanation. God is not ‘in the dock’ of our tribunal. However, many of us as readers of Job, or the Bible as a whole, do not come away with such understanding and humility.

Quoting from the Beveridge translation of the closing paragraphs of Sec. 10 we have Calvin’s conclusion as to our proper “endurance” response. (In the D&P translation this quoted portion begins on the bottom half of p.81) .

It must therefore be our study, if we would be disciples of Christ,

Calvin, J., & Beveridge, H. (1845). Institutes of the Christian religion (Vol. 2, p. 282). Edinburgh: The Calvin Translation Society.

to imbue our minds with such reverence and obedience to God

as may tame and subjugate all affections contrary to his appointment.

In this way, whatever be the kind of cross to which we are subjected,

we shall in the greatest straits firmly maintain our patience. Adversity will have its bitterness, and sting us.

When afflicted with disease, we shall groan and be disquieted, and long for health; pressed with poverty, we shall feel the stings of anxiety and sadness, feel the pain of ignominy, contempt, and injury, and pay the tears due to nature at the death of our friends: but our conclusion will always be, The Lord so willed it, therefore let us follow his will. Nay, amid the pungency of grief, among groans and tears, this thought will necessarily suggest itself, and incline us cheerfully to endure the things for which we are so afflicted.

We have several English words that convey staying purposefully with or in a situation that one would not choose to experience. “Remain” is a weak such word. “Endurance” is stronger but carries with it a form of suffering passively. “Perseverance” is yet stronger because it is active, a doing of something, despite circumstances.

Hebrews 11 is sometimes called the “Faith Hall of Fame.” It is a brief summary bio of Old Testament followers of God. A common theme of all of them, as with all the many secular versions of a hall of fame, is determination in the face of adversity, commonly over the course of many years or even an entire lifetime. What is distinctive of Hebrews 11 is the undergirding “faith” is not, as with secular examples, a faith in oneself but, rather, in God Himself, often despite all experiential conditions.

Then when we get to Hebrews 12, The Holy Spirit turns the examples of Chapter 11 toward each of us, without exception. Consider the below passage:

12:1 Therefore, since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses, let us also lay aside every weight, and sin which clings so closely, and let us run with endurance the race that is set before us, 2 looking to Jesus, the founder and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is seated at the right hand of the throne of God.

3 Consider him who endured from sinners such hostility against himself, so that you may not grow weary or fainthearted. 4 In b you have not yet resisted to the point of shedding your blood. 5 And have you forgotten the exhortation that addresses you as sons?

“My son, do not regard lightly the DISCIPLINE of the Lord,

nor be weary when reproved by him.

6 For the Lord DISCIPLINES the one he loves,

and chastises every son whom he receives.”7 It is for DISCIPLINE that you have to endure. God is treating you as sons. For what son is there whom his father does not discipline? 8 If you are left without DISCIPLINE, in which all have participated, then you are illegitimate children and not sons. 9 Besides this, we have had earthly fathers who DISCIPLINED us and we respected them. Shall we not much more be subject to the Father of spirits and live? 10 For they DISCIPLINED us for a short time as it seemed best to them, but he DISCIPLINES us for our good, that we may share his holiness. 11 For the moment all DISCIPLINE seems painful rather than pleasant, but later it yields the peaceful fruit of righteousness to those who have been trained by it.

12 Therefore lift your drooping hands and strengthen your weak knees, 13 and make straight paths for your feet, so that what is lame may not be put out of joint but rather be healed. 14 Strive for peace with everyone, and for the holiness without which no one will see the Lord.15 See to it that no one fails to obtain the grace of God; that no “root of bitterness” springs up and causes trouble, and by it many become defiled; 16 that no one is sexually immoral or unholy like Esau, who sold his birthright for a single meal. 17 For you know that afterward, when he desired to inherit the blessing, he was rejected, for he found no chance to repent, though he sought it with tears.

The Holy Bible, English Standard Version. ESV® Text Edition: 2016. Copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. (all highlighting is mine)

In the above passage I’ve highlighted by underlining the references to the reader (the “you” in the text), and by bold references to doing or being. Note further the many repetitions of the word “discipline” in its various forms.

As we have discussed in previous Calvin study weeks, the word “discipline” is the root of “disciple” and coveys the idea of learning, being developed, shaped, growing to a particular maturity. It does not, primarily, mean what is usually the first thought namely some for of punishment. Disciple involves correction but purposefully toward a difficult to achieve end. Using the discipline required of one’s hands in various contexts is instructive. Playing a musical instrument such as a piano, violin, guitar, drums, much attention from the very first lesson is about the positioning and movement of one’s hands, contrary to our natural inclinations. Such instruction (discipline) continues throughout all of one’s musical training as ever increasing refinement is required to achieve mastery of any particular instrument. Moving to sports examples, the same holds true for golf, especially that, but also basketball, football quarterbacks, and even football lineman on both offense and defense where hand ‘combat’ plays an important role.

Returning to Hebrews 12:1 we see the command that we are “to run with endurance the race that is set before us (literally, “laid out before us” as a road before our feet extending to some horizon). “Endurance” is not about being steadfast in position at that present point in that road. “Endurance” is about pressing on, going forward, and staying on the road, despite obstacles and even barriers on the road, and manifold tempting diversions on each side of the road, including the always-present temptation of making a U-turn and returning to some starting point.

Self-denial is not our nature’s choosing, but the opposite. Taking up the (our) cross is even a more contrary-to-nature idea as it carries with it a lifetime permanence. And so, the requisite condition of “endurance” is not event-driven, but a life-condition. How can this be anything but somber news?

If suffering in whatever forms is the presented issue, what then is man’s response?

If the answer from the Scriptures is it is God’s Will, then what is to be our reaction. Again, there are various possibilities:

But Calvin gives us a totally different answer: “God forms us through affliction” (Sec. 3.11, D&P p.82). The difficult idea expressed by “forms us” in D&P’s translation, is expressed in alternative translations and by Calvin’s hand as below:

the hand of God tries us by means of affliction (Beveridge, 1845)

we are exercised with afflictions by the Divine hand (Allen, 1816)

the hand of God doth exercise us by afflictions (Norton, 1599)

estre exercitez de la main de Dieu par afflictions (Calvin’s original French text)

(be exercising from the hand of God through afflictions)ut manu Dei nos exerceri per afflictiones intelligerent

Calvin, J. (1834). Institutio Christianae religionis (Vol. 1, p. 458). Berolini: Gustavum Eichler. (the final quotation)

(by the hand of God, we are carried out by affliction [we should] understand)

Let’s think more deeply on the idea of “forms” or “exercises” as God’s hand in His use of afflictions. Latin “exerceri” is the present passive infinitive verb of the word “exercero” (exercere), which range of meaning is: train, drill, enforce, cultivate. So it can convey the immediate aspect, by the idea of train (or drill), or a longer-term perspective by cultivate, or the imposed experience by enforce, all of which have some purpose, an intention.

“Forms,” as an alternate translation combines all of these perspectives and is, I think, a brilliant one-word synopsis. It comes from the Latin word “forma,” which means form but also shape, contour as in making something beautiful by carving, chiseling, sculpting. Today there’s a vast industry of plastic surgery known as by terms such as “cosmetic surgery” (coming from the Biblical Greek word “kosmos”–worldly beauty or order), and esthetic (aesthetic) surgery. The goal of such is the improvement of physical appearance. God’s use of affliction is a transformation of inner and ultimate experience and appearance, which, ironically, may include an actual degradation in outward, physical appearance.

None of these words or the ideas behind them suggest a meaningless, purposeless experience. The late Elisabeth Elliot, who knew a lot about adversity, expressed this as “your suffering is never for nothing,” and, the completely counter-cultural, counter “the self” claim: “suffering is the gateway to joy.” (But, we must be ever reminded that we often do not, and will not, know what is was “for”).

The late Elisabeth Elliot (1926 – 2015) is a well-known Christian author of many books. She first became well-known as the wife of missionary Jim Elliot who was murdered in the mission field early in their marriage. She later remarried and subsequently again became a widow. Along her life’s journey as a missionary herself, writer, counselor, teacher, she had many experiences of adversity including, in her latter days, the onset of dementia, a particularly difficult experience for one so gifted in mind and the craft of writing. Her memorial website is here:

Now gone home to her welcome reward, her experiences in the high intensity adversity moments and long periods of just ‘ordinary’ adversity, have blessed many through her learned perspective and writing. Below are a few insights from several of her books that closely relate to this topic of Calvin’s Chapter 3:

Suffering is Never for Nothing.

Hard times come for all in life, with no real explanation. When we walk through suffering, it has the potential to devastate and destroy, or to be the gateway to gratitude and joy.

Elisabeth Elliot was no stranger to suffering. Her first husband, Jim, was murdered by the Waoroni people in Ecuador moments after he arrived in hopes of sharing the gospel. Her second husband was lost to cancer. Yet, it was in her deepest suffering that she learned the deepest lessons about God.

Why doesn’t God do something about suffering? He has, He did, He is, and He will.

Suffering and love are inexplicably linked, as God’s love for His people is evidenced in His sending Jesus to carry our sins, griefs, and sufferings on the cross, sacrificially taking what was not His on Himself so that we would not be required to carry it. He has walked the ultimate path of suffering, and He has won victory on our behalf.

This truth led Elisabeth to say, “Whatever is in the cup that God is offering to me, whether it be pain and sorrow and suffering and grief along with the many more joys, I’m willing to take it because I trust Him.”

Amazon.com description, published by B&H Books, 2019.

Discipline: The Glad Surrender

In our age of instant gratification and if-it-feels-good-do-it attitudes, self-discipline is hardly a popular notion. Former missionary and beloved author Elisabeth Elliot offers her understanding of discipline and its value for modern people. Now repackaged for the next generation of Christians, Discipline: The Glad Surrender shows readers how to – discipline the mind, body, possessions, time, and feelings-overcome anxiety-change poor habits and attitudes-trust God in times of trial and hardship-let Christ have control in all areas of life Elliot masterfully and gently takes readers through Scripture, personal stories, and lovely observations of the world around her in order to help them discover the understanding that our fulfillment as human beings depends on our answer to God’s call to obedience.

Amazon.com, published by Revell (2016)

I like to think that Elisabeth and John Calvin have met up in some way in the heavenlies, where John has given thanks to Elisabeth for her insightful books on discipline and suffering and she John for his pioneering insights especially in Chapters 2 and 3 of his Little Book. They are very different people but through the Scriptures, and the life-work of the Holy Spirit in and on them they came to very aligned insights.

On D&P p. 81ff, Chapter 3.10, Calvin offers some simple counsel as to what we can do to become true disciples of Christ, in this particular context of bearing the cross and self-denial. He says: “…we should make it our aim to soak our mind in the the sort of sensitivity and obedience to God that can tame and subdue every natural impulse contrary to His command.”

After he then notes that such action does not somehow magically prevent adversity nor our deep experience of suffering, he adds this is to be our pre-ordained perspective: “But this will always be our conclusion: nevertheless the Lord has willed it, therefore let us follow His will…in order to incline our hearts to endure those things with which they’re inflicted.”

Calvin closes Chapter 3 (D&P p. 83) citing what is likely to be the most beloved verse in the New Testament, Romans 8:28: “All things work together for good…” This has comforted many over the centuries and circumstances.

However, this single verse is not the whole thought as verse 28 flows into 29, and should be (my opinion) considered as one sentence, expressing one complete thought. There is a concrete reason expressed in this text for “all things working together for good” as is the reference (in vs. 29) of God who “foreknew and [unto] predestined” and that is restoring fallen man to the image of God to which he was originally created. This connects us back to our Chapter 1 studies and the separate collection of observations on “Image” given here.

The ESV reverse interlinear with my annotations is shown in the below pdf is worthy of careful study and reflection:

The Westminster Confession of Faith (WCF) is a founding document of the Reformed Faith codifying certain core principles of the Christian Faith based upon the Scriptures. It is written in brief chapter form. Chapter 6 of WCF has a particular connection to this present Chapter 3 of Calvin which admonishes us to follow the command of taking up the cross, to be true disciples of Christ, in the context of our self-denial. Below is a brief recapitulation of WCF Ch 6 to highlight this connection. In the pdf directly below is the full text of the WCF chapter:

Let us begin with the fifth paragraph (section). Breaking up paragraph five clause-by-clause it says:

1 This corruption of nature,

WCF, Chapter 6, Paragraph 5, https://www.pcaac.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/WCFScriptureProofs.pdf (ordering by clause is mine)

2 during this life,

3 doth remain in those that are regenerated;

4 and although it be, through Christ, pardoned, and mortified;

5 yet both itself, and all the motions thereof, are truly and properly sin

These five clauses, as shown, are expressions of the thrust of Calvin’s Little Book (on the Mature Christian Life). Any diagnosis requires a correct, full grasp of the disease of the human (fallen) condition.

With all novels, we have the basic structure that there exists a “hero,” and the essential, first question is “what does the hero want?” The rest of whatever is the story unfolds from there.

Considering Calvin’s Little Book, we can ask the parallel, big picture question, of “us,” namely: “what’s our problem?” or “what is our true condition?”

As we have seen throughout Calvin’s Chapter 1 – 3, his claim, based on the Scriptures, that man’s condition is fallen disastrously far from the absolute Holiness of God while, yet, we have been called to a model (framework) for the pursuit of that righteousness. The first three clauses of WCF 6.5 makes such claim clear: “this corruption of nature,” which meaning we will turn to momentarily, is with each of us in our period and place in spacetime even though we have been given new life from and of God through the unique and finished work of Christ. This should be deeply troubling and comforting at the same time: troubling in that we have not been experientially freed from something awful even to the point of our death, but comforting in that the pain we will each inevitably experience in our innermost selves does not represent our true standing before God nor foreshadow our ultimate destiny of freedom from sin.

Now let’s turn to WCF regarding the reference above to “this corruption of nature.” The preceding paragraph of WCF, 6.4, tells us this:

1 From this original corruption,

IBID

2 whereby we are utterly indisposed, disabled, and made opposite to all good,

3 and wholly inclined to all evil,

4 do proceed all actual transgressions.

We see above, first, our true nature with respect to the holiness of God that derives “from this original corruption.” Note the use of universals: “are utterly,” “made opposite,” “wholly inclined,” “all evil,” “all…transgressions.” We are not just ‘off’ by a little, or damaged, banged up here and there, stuck with a body that doesn’t want to do what we want. No, we are top to bottom, inside to out, past to present to future, mind, body, soul, and every other way, utterly in a state of ruin, as was the pre-Creation in Gen 1 (utterly without form and void). We are like Isaiah when he saw God he said of himself “I am undone” (completely disordered), as our bodies will soon demonstrate upon our death, joining every single human who has died before us, with every treasure they thought to have acquired.

Now let’s turn to WCF regarding “from this original corruption.” The preceding two paragraphs of WCF 6.2 and 6.3, which say this:

Para. 2:

IBID

1 By this sin they[Adam and Eve]

2 fell from their original righteousness and communion with God,

3 and so became dead in sin, and

4 wholly defiled in all the parts and faculties of soul and body.

Para. 3:

1 They being the root of all mankind,

2 the guilt of this sin was imputed;

3 and the same death in sin, and corrupted nature,

4 conveyed to all their posterity descending from them by ordinary generation.

We understand clearly now in the 21st Century that our physical bodies are built up from a DNA ‘recipe’ (more accurately, “program” or “algorithm”), located within every cell of our body. We are not a frog, or an egret, our dog. We cannot “be,” in terms of our physical instantiation, anything but what we have been made to be from the first cells of our physical creation at the moment of conception in the womb’s of our mothers, everywhere in the world, for all people.

In like manner, the Scriptures disclose to us, that “what’s our problem” had a like formation, it came to and in us, at every point of our inner being, by imputation. That formation caused physical death of our bodies, though it plays out over time, our respective lifetimes, but we are dying in our own processing ultimately to die. But more-significantly, there came to our inner being, not only our bodies, another kind of death, far more serious, toxic, and fatal–because such is a death under the wrath of God–and, humanly considered, incurable, exactly as our bodies are incurably doomed to physical death.

The doctrine of imputation is big and beyond our scope here. But, briefly, in Romans Chapters 5 through 8 we see that there is a second imputation, by a “second Adam,” Jesus Christ, who provides the eternal ‘cure’ for what is incurably “our problem.” We bring to God the one thing, and the only thing, that is truly ours alone, our sin and the fallen nature source of it, and God provides the eternal cure, that which only He can provide, our regeneration.

Yet, and here is the great issue underlying the entire Little Book of Calvin, we live in this spacetime period with two realities: our regenerated new life in Christ, and our still not extinguished fallen nature in Adam. Our minds naturally seek simplicity and head toward either truth as exclusive, namely: we are regenerated and without any inclination toward corruption that had been our old nature, or, we’ve never been regenerated at all because we experience seemingly without interruption the work and underlying passions of the fallen flesh. But it is not either / or; both conditions are true, and thus we have the call to follow the one to ‘home,’ reflecting, progressively, our true, new identify (image) of Christ in God.

In Hebrews 12, considered briefly previously, Christ’s work of regeneration (redemption, propitiation, imputation) was predicated on His “endurance.” The Greek word so translated, hypo-meno, occurs four times in Hebrews: 10:32 and three times in Chapter 12 at vs. 2, 3, and 7.

The Scriptures are teaching us (at least) two things here. First, that there was an endurance element of the Work of Christ in regeneration. And second, that such endurance is a model of what we have been called to do as our pursuit of the mature Christian life. Consider these portions of Hebrews 12:

12 1Therefore, since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses, let us also lay aside every weight, and sin which clings so closely, and let us run with endurance the race that is set before us, 2 looking to Jesus, the founder and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is seated at the right hand of the throne of God.

3 Consider him who endured from sinners such hostility against himself, so that you may not grow weary or fainthearted. 4 In your struggle against sin you have not yet resisted to the point of shedding your blood. 5 And have you forgotten the exhortation that addresses you as sons?

“My son, do not regard lightly the discipline of the Lord,

nor be weary when reproved by him.

6 For the Lord disciplines the one he loves,

and chastises every son whom he receives.”7 It is for discipline that you have to endure. God is treating you as sons. For what son is there whom his father does not discipline?

Hebrews 12, ESV (highlights mine)

Recall as we have previously discussed at length, that “discipline” is not punishment but the work of training, refinement, growth to maturity, purification. Calvin’s connection of “taking up the cross” (quoting Scripture) with “self-denial,” the subject of Calvin’s chapter 2 and 3, is that such “discipline” and “endurance” is the necessary framework for the twin realities of our present life: we have been made wholly righteous in the sight of God, in Christ, and, yet, sin remains both in its acts and nature, a war with our new nature, seeking to prevent or tarnish the image of Christ to which we have been called ‘home.’

“Repentance” is a word we all know but do not all understand. It is not a pleasant word, but it, more precisely–the idea it carries–is the direction back to the right road.

In the wonderful book by John Bunyan, Pilgrim’s Progress, one temptation that befell the main character, Christian, was crossing a stile (a small, double-sided ladder used to climb over a fence) to travel what looked to be a more pleasant route known as Bypass Meadow. But, as Bunyan a long-time preacher and small church leader well knew, Bypass Meadows leads to bad ends, in the story to a prison known as Doubting Castle. After much suffering there, Christian and his travel companion escaped by use a hidden key he carried which were the promises of God. Once outside the prison, they hustled back from fear of being re-captured to the stile. There they went back over the fence to regain the straight and narrow road from which they had diverted. That is a picture of repentance.

Book 3 of Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion is titled “The Mode of Obtaining the Grace of Christ: The Benefits It Confers, and the Effects Resulting from it” (from the Beveridge 1845 translation). Of the 25 chapters in such Book 3, five of them have been separately published since the early date of publication of the entire Institutes (1540) under various titles such as studied here as the Little Book. So in the study of the limited scope of the Little Book we are bereft of Calvin’s insights and commentaries in the 20 other chapters of Book 3, and the 65 chapters in the other Books of his Institutes.

One of the important missing themes in the Little Book is our present subject of “repentance.” Doing a word search of “repent*” in The Institutes yields a vast number of references: 339. Collecting all of them and cohering Calvin’s discussion of repent / repenting / repentance is beyond our scope here. Instead, given in two pdfs below are selected collections of Calvin’s discussions on “repentance” from Book 3:

and

We should not miss the important connection between the presence of an extensive discussion of “repentance” in Book 3 with the title of Book 3 referencing “the mode” and “the benefits” of obtaining “the Grace of Christ.” Repentance is one key element.

There are many many example biographies in the Bible, both Old Testament and New, that shows repentance leading to Grace. Here are a select few. You are invited to make a mental note to see other examples in your regular reading and meditation; you will find a great many, so many that this topic is journal worthy for recording your observations.

Luke records a well known scene recounted by the Lord. In the Temple area of Jerusalem, the holiest center of Judaism, are two men from absolutely polar opposite standings in the religious hierarchy: a Pharisee and a Publican (aka “tax collector”). The Pharisee was representative of the highest, most religiously committed class of the Jewish people, living according to the strictest interpretation of the Mosaic Law. The Publican was in consort with the Roman government, collecting taxes, frequently in excess of that required to pay Rome its due to further line his own pockets above what he was to be rightly paid for his service to Rome; in the eyes of the Jewish people, he was the lowest of the low, a traitor, a criminal with legal powers of compulsion given to him by also hated Romans, and so an utter betrayer of the legacy of Judaism and the Law.

They were, quite amazingly, both praying at the same time, though not exactly in the same place. The Pharisee was right in the visible center of things, as he was of all men most entitled to be, dramatically public, almost as a stage performer, going about his prayers to God Who he so outwardly served. The Publican, being utterly downcast of his standing before God, as he inwardly grasped the Holiness of God and his own complete unholiness, stood afar off.

The Pharisee was praying looking into “heaven,” believing he was face-to-face with God, standing in a state of legal righteousness before Him. The Publican was looking down, as a criminal knowing his guilt does.

The Pharisee was formally praising God but inwardly he was praising himself. The Publican, by beating his chest, was crushed under the weight of his total guilt, enacting the grief of mourners in the presence of the dead.

Jesus must have shocked his audience in this telling because He ends the recounting by saying it was the Publican, and not the Pharisee, that went away justified by God. How could this be? It was that the Publican knew something true about himself, and about God’s Holiness, and the smallest hope of God’s Grace of forgiveness, to have presented himself in a state of repentance. The Pharisee, being the “great” man he saw himself to be in terms of religious practice (and The Religion Industry, TRI), then did not sense any need of repentance. Further, the Pharisee would have considered the Publican as one so evil as beyond reach of any act of repentance, whereas the Gospels later reveal it is the Pharisees who are both in need and are incapable of such repentance.

This contrast links back to the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5). The “beatitudes”–that each begin with “Blessed! are”–begin with those who are the poor in spirit…those who mourn…the meek…who hunger and thirst for righteousness…” (Matt. 5:3-6, ESV). These words tell us of the Publican’s heart, revealed by the Lord’s description of him.

In the Old Testament there is another notable contrast of two men who overlapped in time but were opposite in their humility before God. King Saul had, finally, come to understand that David, from a different family, would be his successor king, instead of Saul’s own son Jonathan, or any other biological heir. This change in line of succession was usually the cause of great carnage as the heirs of the former king are banished or killed by the new king to secure the new king’s throne and own line of succession.

But once King Saul knew that David, in his time, would become King, it was Saul’s responsibility before God to accept it, as his son Jonathan did. But Saul not only would not submit to such determination by God, Saul did everything he could to kill David despite David’s loyalty to Saul and faithful military service on behalf of the King. We have only a glimmer of Saul’s possible repentance upon the sparing of his life a second time by David, then a fugitive under Saul’s judgment of death.

David was no sinless man, nor, later, a sinless King. We all know of his failures including the prideful numbering of Israel, and his adultery with Bathsheba that lead to the murder of her husband Uriah, a faithful soldier of King David. There were other examples. But, yet, God said that David was a man after God’s Own heart. And David is one of the leading human writers whose texts are including in the Old Testament, including much of the Book of Psalms.

How can this be? Again, the distinction between David and Saul, as between the Publican and the Pharisee, was and is repentance. When Nathan the prophet came to David with a ‘story’ about a rich ruler who sought a lamb to slay to feed his guests, instead took a pet lamb of one of his subjects, despite having a vast flock of lambs of his own. King David sitting as judge rose in anger, as we all would, and declared the guilt of such cruel ruler. And Nathan then said to David, those penetrating words: David…”you are that man.” David then recognized that he was that rich and utterly unfeeling ruler having many ‘lambs’ who instead took the one precious ‘lamb’ (Bathsheba) of one of his servants (Uriah), even to the point of killing the ‘lamb’s’ owner. That led David to repentance, and a return to Grace, though much sorrow followed in his life.

The original manuscript (mss) words in Hebrew and Greek that are translated most-often by the word “repentance” are given below.

Given below are key verses (from the ESV) of where the New Testament (NT) Koine Greek word of metanoia is translated as repentance. The word means, literally, to change one’s mind. That seems simple as it does not call for some great acts of penance and self-flagellation. But changing one’s mind, truly, is truly a most-difficult action, especially for embedded perspectives, opinions, and behaviors.

The imagery of repentance in the Old Testament (OT) is far richer than just the occurrence of the translated word itself. There are many occasions whereby God’s people fell into trials and even captivity from which they cried out to God for deliverance, often in the humility of powerlessness, and the recognition of having fallen away from God by its pursuit of idols, or by bare neglect.

The root meaning of the primary Hebrew word is “to turn back,” even the idea of a complete 180 degree change, as a returning to a place where a departure from a correct path began, like the Pilgrim going back to the stile. That is a hard thing to do because such departure, at the time, as those things typically appear, looked to be a good idea, even a better way. The Book of Proverbs can be viewed as a whole as a father instructing his son exactly on such departure temptation by the recurring contrast between the “wise man” and the “fool.” What’s really the difference? Wisdom is about making choices, and in particular “good” choices based upon the understanding of where each choice will lead, even if known only in broad-brush terms. The wise man foresees where such departure will go, and anticipates its full measure of consequences, and (importantly) chooses not to so turn away from the right path. The fool either has no such wisdom to restrain himself, or hearing of it chooses to ignore it, and follows impulse, feelings, false promises, short cuts, or whatever other lure, like bait on a hook, leads him.

Given below are the principal occurrences of the Hebrew word translated “repent*” (from the ESV) in the Old Testament:

The story of Jonah is almost universally known, but known as a story about a man eating fish (actually it was a mammal) who actually did not “eat” the man (Jonah) but spat him out as disgusting morsel not worth digesting. But he deposited him back on the shore of Israel from which he had paid his fare to sale away as far as possible from there.

But the real story of Jonah is repentance. First is Jonah’s repentance. Jonah had been clearly instructed by God to go to Nineveh, capital of the hated and mighty Assyrian Empire and preach that they should repent. Jonah loathed this assignment, partly because all Israel hated the Assyrian people because they were non-Jews and a rapacious military power seeking conquest and enslavement of all its neighbors and beyond.

As a second point, it is certain that going to such city and preaching that the God worshipped by Israel was the One True God would be viewed as a hate-deserving message, even seditious, by the Assyrian people and leaders.

Finally, Jonah might have feared that God would use Jonah and that message of repentance to cause the Assyrians to repent, and so escape what otherwise would have to be God’s ultimate judgment and condemnation.

So, Jonah, as the ultimate example of a fool, thought he could solve all these downsides of obeying God’s direct command by getting on a ship bound for the furtherest reaches of the then known world, Tarshish (likely what we know as Spain, at the opposite end of the Mediterranean Sea).

After his ride ‘home’ by the sea creature, and God’s repeating His command to go to Nineveh, Jonah repented at his impulse to flee his assignment, as he did indeed go to Ninevah and did speak as instructed the very words of God. But he did so with as much reluctance and passive-aggressive mentality as the most recalcitrant teenager who ever lived. Jonah seems to have sought to give the worst evangelistic message in the history of the universe, almost to the point of defying God to cause such words to create repentance by the least likely people. (It is almost humorous to read the story of Jonah’s evangelistic ‘campaign’ in that city; he was likely the most-reluctant preacher in history).

But in a miracle far far greater than the great sea creature, those words were used by God and true repentance of the Assyrian people did occur.

It was Jonah himself who struggled doing repentance that was the subject of his assignment from God. We get a closing view of Jonah’s sorrow for a small plant that had provided him some shade by virtue of a one day growth than he did the vast number of Assyrian people who had genuinely repented of their having been worshippers of pagan gods. God had to speak to Jonah yet a third time to lead him to a repentance of heart, not just of body but of his words of despair over plant that died overnight.