This week we will conclude Calvin’s Ch of his Little Book, and this particular study of this “Great Book.”

Calvin’s Heading for Ch 6, Sec.s 5-6

5. Second, Impatience and immoderate desire.

Remedy of these evils.

The creatures assigned to our use.

Man still accountable for the use he makes of them.6. God requires us in all our actions to look to his calling.

Calvin, J., & Beveridge, H. (1845)

Use of this doctrine. It is full of comfort.

Bible Texts Cited by Calvin in Ch 6, Sec.s 5-6

(Note: Calvin did not cite Luke 16:2, but it was included in the D&P translation and so it is given above with Phil 4:12).

Calvin’s Key Points

In Sec 4, Calvin gave a broad summary of this final chapter by two opposites:

There is no more certain or reliable path for us than contempt of this present life

Calvin, Ch 5.4, D&P p. 119

and meditation on heavenly immortality.

In Sec. 2, Calvin made clear that we are free to delight / enjoy God’s provisions for us in this present life as it is clear that He intended such by the beauty and fullness of His provisions. But the danger is that we can become so focused on such delights as to lose track of God’s calling, and the balance required of us.

This metaphor may be helpful to make clear this distinction. Consider a person called to be on a journey, often arduous, but sometimes not. During the day’s travels, and particularly at evening time, such traveler needs refreshment to enable and restore the body, and to some extent the soul as well. The next day, in response to the call of duty for his journey, the traveler must again begin the journey. To cease the journey to live in the experience of delight would be to abandon the traveler’s calling, a most-serious mis-alignment of priorities. On the other hand, to deny any kind of refreshment, restoration from some sense of life as duty only, requiring extreme self-severity, is to be out of balance in the other direction.

If one reads the Gospel narratives looking at such balance points, where both delight and journey-pursuit occur, we can see the Lord Himself did both. He was a continual traveler. Yet there were repeated times of rest and refreshment. His public ministry began by being at, and engaged with, a large wedding celebration (necessitating 180 gallons of wine!), likely a multi-day festival, and ended with the intimate experience of what we know as “The Last Supper,” a special time with His closest disciples.

Consider this verse from the Psalms:

It is in vain that you rise up early and go late to rest, eating the bread of anxious toil; for he gives to his beloved sleep.

Psalm 127:2 ESV (highlights mine)

Calvin’s Key Point #1: Moderation

In Sec. 4, Calvin brought forward several dimensions of his first point, moderation in all things, based on the text we considered in Week #19, 1 Cor 7:29-31. He used phrases such as

- “learn to bear scarcity,”

- “all with moderation,”

- “hold the things of this world lightly,”

- “put to death …immoderate appetite for food and drink,”

- “put to death …ambition, pride, haughtiness, and dissatisfaction,”

- “eliminate …stockpiles of superfluous wealth,”

- “curb extravagance,” and

- avoid turning gifts given into “obstacles” on one’s journey.

In the deep dive study of the 1 Cor 7 we highlighted a small but important word that recurs in this passage: “as” where it is used to portray one’s attitude to things and experiences of this present world that are not in any way wrong, but should be viewed, and used, without seeing such as the meaning of life.

Calvin Key Point #2: Abstain from Excessive Longing

In Sec. 5, Calvin draws attention to the emotion and orientation driven by “longing,” (a word D&P translates twice on p. 121).

Such feeling of “longing” can most-readily be seen in those of us who are in some particular need because of a lack or want of some kind.

But, let us use discernment as to one’s longing. Calvin makes the point that if longing is a governing emotion during situations of genuine want, it will remain such an emotion even after (if it should happen to be the case) when the original want has been satisfied.

The coveting impulse cannot be escaped by prosperity.

He, or she, that gets much, especially in a brief period, will discover shortly that a new dimension and subject matter of coveting has been aroused. Even the extremely wealthy can be, and often are, covetous, even extremely so, be it for ever more luscious living circumstances, or greater experiences, or more numerous accoutrements, or newer / more-glamorous spouses and friends, or greater honors, or all of the above.

Calvin Key Point #3: Hold to the Rules of Love

Here Calvin calls on the Bible’s parable of the steward who is called to “turn in the account of your management” (Luke 16:4) We, likewise, have been given the management of certain possessions, and we are and will be called to give an account of what we have with them, specifically as to:

- Self-control, soberness, frugality, and modesty on the one hand,

- Luxury, pride, showiness, and vanity on the other hand. (D&P, p. 123)

Calvin notes that motive which is joined with love will do the former and not the latter That is the inordinate pursuit of pleasures that “drag man’s heart away from [1] integrity and purity, or [2] muddle his thinking. (D&P, p. 123)

Calvin Key Point #4: Consider all of One’s Actions with Regard to One’s Calling

In the closing Sec 6 of his closing Ch 5, Calvin returns to a key idea that began Ch 1, namely that of each of us having a calling, unique to each of us in certain particulars.

Calvin uses the terms “particular duties” in one’s “station in life,” one’s “callings” “rank in life” “post assigned…by the Lord.” (D&P, p. 124, where Calvin references “calling(s)” three times and “post” twice).

Further, Calvin writes: “It is sufficient that we recognize the calling from the Lord to be the principle and foundation of good works in all our affairs.” And he follows with further reference to “frame one’s actions,” “calling” “keep to the right course,” “duties,” within one’s “various spheres of life,” directed toward a “goal,” being “well-composed,” not overstepping one’s “boundaries.” (D&P, p. 125).

Calvin’s Conclusion

The final sentences of Ch 5, and this five chapter interlude of his Book 3 of his four book Institutes, Calvin writes:

Each person in whatever his station in life will endure and overcome [whatever obstacles] convinced that his burden has been place upon him by God. Great consolation will follow from all of this. For every work performed in obedience to one’s calling, no matter how ordinary and common, is radiant–most valuable in the eyes of our Lord.”

D&P, p. 126 (emphasis mine)

His last phrases of his final sentence are worthy of a deep dive into Calvin’s original Latin expression.

1. quod (modo tuae vocationi pareas)

Calvin, Latin original

2. [non] coram Deo resplendeat

3. et pretiosissimum habeatur

Phrase 1: Our Vocation and Duty

Considering Phrase 1 above, we have “that whatever your” (quod modo tuae), introducing two vitally important words: “vocation” (vocationi) and “be subject to / duty” (pareas).

“Vocation” derives from the word “vocal” which literally means “call,” that is “to be called.” This is such a deep idea that threads through all the Scripture. We find in Gen. 1 that God speaks, one could say “calls,” all of Creation to come into existence. Upon the Fall of Adam and Eve, God seeks out and calls: “Adam, where are you?” (Of course God knew where Adam was physically, but what was the far deeper matter was where Adam was in terms of life and death, holiness and condemnation). Then God calls Noah out of the antediluvian world. Next he calls Abram (Abraham) out of the utterly pagan River Valley Civilization of ancient Mesopotamia. God calls the various OT prophets who are given God’s Word for them to call the people to repentance and faith. God Sovereignly used Caesar Augustus’s call for everyone to go their home city for Joseph and Mary to journey to Bethlehem, the City of David, being of that line, to give birth to Jesus. And Jesus then called his disciples. Then those who come to faith are the (literally in Koine) “the out called ones” and such is the term of their community of faith (i.e., the church). In Revelation we see the Apostle John being “called” up into heaven (“Come up here!” Rev. 4:1) to see and so record a vision of the latter days. And ultimately God will call us (Rev. 17:14) even, ultimately, out of tombs into everlasting life. (In the ESV, the word “call” occurs more than 800 times in the Bible, which number does not include all the various words for “say” or “speak”).

Connected directly with such “calling” is a “duty,” that is being subject to, prioritizing life and energy, to such “calling.” This is exactly the nature of what we as a parent would say to our child entering high school or college, or military service, or a given career. There needs to be an alignment, particular to the particularity of the calling. Another way of expressing “duty,” which can sound only obligatory, is “to pay attention to,” to “to attend” (focus, give energy toward).

Phrase 2: Resplendent in the Sight / before the Face of God

The next phrase in Calvin’s closing words is: [non] coram Deo resplendeat, “Deo” is where we get “Deity,” and means “God” Himself. “Coram” is related to our word for “cornea,” namely the eye, metaphorically meaning “under the gaze of,” or even “directly face to face.” (Hence, Ligonier Ministries uses the phrase “Coram Deo” as its practical heading for how we should translate a doctrine into life itself).

The word “resplendeat” means to shine brightly, specifically as reflected light. The prefix “re” in Latin can mean “again” (redo, repeat, etc.), or “back”/”backward,” here signifying the idea of reflection from God. The Latin root word “splendeat,” from which we get “splendor,” means to gleam, be bright, radiant, even glitter. As D&P translates the whole phrase, that which we do rightly with respect to our calling, is a great brightness directly apprehended by God, reflecting the virtue of such work, as we have been created in the image of God, back to God, and perhaps even the Glory of God reflected back to us.

(The [non], i.e. “not” reference in this phrase is to the apparent insignificance of our calling, such faithful execution of it leads to such resplendence).

Phrase 3: Our Faithful Response to our Calling is a Possession of Great Value

The final phrase in Ch 5 is: et pretiosissimum habeatur. “Et” is simply “and.” “Habeatur” comes from Lat. “habeo” which is where we get “have.” It’s broader meaning that mere possession, includes think, reason, manage.

Finally, let us consider pretiosissimum. This comes from “pretiosa” from which we like get our English word “precious,” and means “that which is costly,” particularly that “of great value.”

A useful, very humble, reminder of what we bring to God in our fallenness is this and this only: we contribute nothing to our salvation but the sin requiring it. However, on the ‘other side’ of redemption, is regeneration by Grace though Faith alone. And it is on such side that we have our individual calling, with its attendant duties and responsibilities, which when performed brings forth a radiant image before the Face of God.

Anti-Covetousness

(Most of the below text has been gathered into a Special Topic on “Coveting” here).

Previously Calvin made clear that we are privileged to enjoy the blessings of God in this life, bounded by several principles: the flesh cannot be the ruling authority of the scope of such enjoyment-seeking, what is rightfully enjoyed does not impede our journey to maturity and our heavenly home, and each enjoyment leads us to greater gratitude to God as the source of such delights.

Now, Calvin begins Ch 5.5 with the situation in which we may be in a condition of want. The danger here is coveting that which we do not have, and perhaps cannot have. This may include both those things and experiences which could be proper delights on our journey (Pilgrimage) and those which are not (the lusts of the flesh, and the eye).

The underlying issue here is “covetousness.” So let’s think about this word.

The Ten Commandments

An interesting exercise is to make a list of 10 universal principles of rightful behavior for a people living together, under God. What would you chose? What would you leave off?

The three obvious choices would include “no stealing,” “no murder,” “no violations of the sexual boundaries of marriage.” Clearly doing otherwise would dishonor God and our neighbor, even a visitor / stranger to one’s community. These would likely be choices made even by what we know to be criminal organizations. How is that? Well, such the members of such organizations are arrayed to commit “crimes” against “the other” (whatever group is such) but never within its own membership. And violations of such internal rules may be dealt with very harshly including killing the offender (which would not be deemed “murder” but justice, namely a lawful killing within the rules of the organization).

That leads seven more to go universal rules to make the 10. And now it is harder to pick out the obvious ones. Let’s see what God decreed:

20:1 And God spoke all these words, saying,

2 “I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.

3 1 “You shall have no other gods before me.

4 2 “You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. 5 You shall not bow down to them or serve them, for I the Lord your God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who hate me, 6 but showing steadfast love to thousands of those who love me and keep my commandments.

7 3 “You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain, for the Lord will not hold him guiltless who takes his name in vain.

8 4 “Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy. 9 Six days you shall labor, and do all your work,10 but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God. On it you shall not do any work, you, or your son, or your daughter, your male servant, or your female servant, or your livestock, or the sojourner who is within your gates. 11 For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, and rested on the seventh day. Therefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy.

12 5 “Honor your father and your mother, that your days may be long in the land that the Lord your God is giving you.

13 6 “You shall not murder.

14 7 “You shall not commit adultery.

15 8 “You shall not steal.

16 9 “You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor.

17 10 “You shall not covet your neighbor’s house; you shall not covet your neighbor’s wife, or his male servant, or his female servant, or his ox, or his donkey, or anything that is your neighbor’s.”

18 Now when all the people saw the thunder and the flashes of lightning and the sound of the trumpet and the mountain smoking, the people were afraid and trembled, and they stood far off19 and said to Moses, “You speak to us, and we will listen; but do not let God speak to us, lest we die.” 20 Moses said to the people, “Do not fear, for God has come to test you, that the fear of him may be before you, that you may not sin.” 21 The people stood far off, while Moses drew near to the thick darkness where God was.

Exodus 20, ESV (enumeration mine)

So the obvious three are #6, 7, and 8 on God’s List of 10. Bracketing these three, at #5 and #9, are honoring one’s parents, which certainly includes positive affirmations of them, and which comes with a promised blessing for doing so) and (#9) honoring our neighbors by never speaking falsehoods regarding them, which of course dishonors them and does so wrongly. Now we have five governing principles.

Then we have the first four, #1, 2, 3, and 4, all of which honor God, including #4, a day set aside from the pursuit of one’s work (and agenda) to recognize the gifts and calling of God. In a humanist worldview, driven by the “science” of the “enlightenment,” it is very unlikely that any of these four would be recognized as life principles. Actually the contrary is more likely to be the case.

Now we have nine of the 10. What’s left?

You Shall Not Covet

Note the final Commandment above: “you shall not covet” as to a comprehensive list of things you do not have:

- House

- Wife

- Servant(s) (human servants)

- Ox

- Donkey

- Anything (else) of your neighbor’s

Each of these distinctions have to be understood in the context of the time and place of the Law’s giving. Few of us live near, or are even aware of someone else’s “ox” or “donkey.” So not coveting such seems like a pretty easy command to obey. If “house” means only literal dwelling, and if we live as many do in ‘cookie-cutter’ housing of apartments or standard developments where each living unit is about the same as the other, this would also seem to be an easy matter. Likewise we do not have human servants in common practice, though people can be very possessive of their baby sitters, so that would also seem to be an easy issue. As to “wife” the fundamental issue is already given as #7 in the 10.

But then there’s the “anything.”

Further, we need to understand that “house” represents more than dwelling, but includes the means of income, i.e. production / business enterprise, that is part of a neighbor’s possession. And the “ok” represents the major tool of farming production, and “donkey” of transportation, and “servants” any of the machinery of daily life that aids the work of life such as would have associated with cooking, cleaning, obtaining water, dealing with garbage, shopping in the marketplace. And the reference to “anything” is to make clear that what is at issue is not the specifics of the enumeration of objects but the underlying attitude of one’s own heart. And that goes to the matter of coveting.

What Does it mean “To Covet?”

The word “covet” comes most directly from the a classic French word, coveitier, which semantic range extends from “desire” (a certain intensity of “want”) to “lust” (a burning craving). The challenge we have with languages like Latin and French (and most other languages) is that the word choice is limited. English has a hugely rich vocabulary, literally hundreds of thousands of words. The Oxford English Dictionary, the gold standard of dictionaries, lists 273,000 “headwords” (essentially lemmas), some 170,000 in current use. That’s an astonishing number. For comparison the vocabulary of the wonderful Koine Greek that God used to write the NT is only about 5,500. (The NT has about 155,000 words, but with a vocabulary of 5,500 different words).

What this means is that a single word in any of these non-English languages has, and has to have, a fairly wide semantic range. This makes determining the specific ‘point’ (level, intensity, aspect) at which any given word should be understood as a significant step of interpretation.

For instance, the Koine word often translated “lust” is epithumía (G1939) which semantic range includes: to desire greatly, having a strong desire, longing, lust. Well there’s a big difference between “longing” and “lust.” It is the word translated as “deceits lusts” (Eph. 4:22), which in many circumstances is an oxymoron (meaning that “lusts” by their nature are “deceitful.” It is translated “lusts” in the famous passage of 1 John 2:16 as to “lusts” (or in the ESV “desires”) of the eye and of the flesh. Yet, epithumía is used by the Lord in Luke 22:15 expressing His longing for celebrating the “last supper” (the Passover supper on the night He was betrayed) with His disciples.

And the verb form of epithumía is what is used in the 10th Commandment forbidding coveting:

epithuméō (G1937) contracted epithumṓ, from epí (1909), in, and thumós (2372), the mind. To have the affections directed toward something, to lust, desire, long after. Generally (Luke 17:22; Gal. 5:17; Rev. 9:6). To desire in a good sense (Matt. 13:17; Luke 22:15; 1 Tim. 3:1; Heb. 6:11; 1 Pet. 1:12); as a result of physical needs (Luke 15:16; 16:21); in a bad sense of coveting and lusting after (Matt. 5:28; Rom. 7:7; 13:9; 1 Cor. 10:6 [cf. James 4:2; Sept.: Ex. 20:17; Deut. 5:21; 14:26; 2 Sam. 3:21; Prov. 21:26]).

Zodhiates, S. (2000)

In the Hebrew text of the OT, the word translated “covet” in the 10th Commandment is:

châmad, khaw-mad’ (H2530); a primitive root; to delight in:—beauty, greatly beloved, covet, delectable thing, (× great) delight, desire, goodly, lust, (be) pleasant (thing), precious (thing).

Brown-Driver-Briggs Lexicon

What is particularly noteworthy about such Hebrew word are the third three occurrences in the OT:

Gen 2:9 And out of the ground the LORD God made to spring up every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food. The tree of life was in the midst of the garden, and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

ESV, highlights mine of H2530, châmad.

Gen 3:6 So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate, and she also gave some to her husband who was with her, and he ate.

Exodus 20:17

“You shall not covet your neighbor’s house; you shall not covet your neighbor’s wife, or his male servant, or his female servant, or his ox, or his donkey, or anything that is your neighbor’s.”

So if we take “covet” as the root meaning of châmad, then as the ESV has translated it in its first use in Gen. 2:9 we can see that every tree in Eden had an appearance of attractiveness, that would draw the observer (Adam and Eve) toward it, much as we experience in a beautifully spread out fresh vegetable display in a grocery store or farmers market. God made it that way, as part of His creating delight in Creation.

Then when we see châmad characterizing Eve’s response to examining the Serpent’s temptation to partake of the forbidden tree of the knowledge of good and evil, Eve saw something to be desired, and which desire drew her to not only take and eat what God had forbade, but also to induce Adam to do likewise, a double evil.

Then the very next use is the 10th Commandment in Exodus 20:17 as we discussed above, and repeated in Deuteronomy 5:21.

There are many nuances of “covet” that are in English: pine, hanker, desire, want, crave, lust, ache (for), wish (for), aspire, envy, thirst, yearn, begrudge. We might even develop a five-star or 10-level intensity ranking that goes from, say, “particular interest” at the mildest extreme, to all out overpowering craving which makes one ready to abandon all moral bounds out of an overwhelming demand to have that one particular thing we do not have.

These nuances and their respective effects upon the one having them has been the tool of many many story tellers. In recent U.S. literature a famous novel, widely read even in high schools, is The Great Gatsby. This story, written by F Scott Fitzgerald in the 1920s, a particularly interesting decade in U.S. history. The book is regarded by many to be on the short list of the greatest American novels, by some accounts the second best after James Joyce’s Ulysses.

The book has been analyzed exhaustively for nearly 100 years by scholars of literature and history, and countless student term papers, theses, and dissertations. What appears to me is that the entire context, and all the principal characters (except “Nick Carraway,” the narrator) are all given by coveting toward covetousness. A primary iconic image in the story is “the green light.” It is literally a nautical channel marker that is located at the end of the female of primary desires, Daisy, now married but formerly in a relationship with the subject character of the novel, Jay Gatsby. Gatsby has a consuming desire (coveting) for Daisy. His house with its dock is directly across a large bay that opens into the Atlantic Ocean. So Gatsby stands at the end of his dock, at night, staring across the bay, seeing only the green light. Of course the green light is a metaphor for coveting (green is even the color associated with such feeling, as “a person green with envy”). And, so, that leads to the common question asked in discussions of the book with students: “What is your green light?” Basically, the ask is what would you be drawing to coveting such that you would commit your entire life and energy to getting even if it was unobtainable, even forbidden to you, even leading to your death? (Gatsby dies in the end–never having re-established his sought for relationship with Daisy).

It is a crazy question. But, it was what the Serpent himself considered when he propositioned Eve in Eden: what could be the ‘hook’ that could cause Eve to not only covet the fruit of the forbidden tree, but to do so in such an urgent, consuming, secret way that she would act of such desire without consulting with Adam, let alone God Himself, but unilaterally making the biggest possible boundary-crossing available to her? The Serpent’s conclusion that the temptation that would carry over from “pleasant” to “desired” to “burning craving demanding satisfaction” was (1) that it was attractive (as were the other trees), but (2) eating it would give Eve superior knowledge powers even to being like ‘gods.’ That is “coveting.”

This is not a harmless question. The context of it, certainly in the novel, is what would you so crave after that you would do anything expending any amount of time required to get something even (perhaps, especially) that which is forbidden to you? Basically, the question posed is this: What is the biggest thing you can think of that would launch an unstoppable, irresistible craving within you that will in effect possess your mind, your body, your talents and interests? In short, what could be so seemingly great that you would be willing to ruin anything and everything, people too?

We see in the OT numerous examples of coveting. Think of Cain who coveted the honor that his brother Abel received from God, and led him to kill. Then the entire line of Cain is described briefly but clearly as those seeking prideful accomplishment, including creating a city whose tower reaches to the heavens. Then we have King Saul who sought to usurp the role of the priest and later opposed even to attempt murder God’s selection for his successor, David. Then David himself with respect to Bathsheba and latter prideful numbering of Israel. Even the entire nations of the Northern and Southern Kingdoms of Israel became covetous of their respective honor. And we can point to the Apostle Paul who self-identified “covetousness” as being the source of his ultimate recognition of his being sinner.

And what of our pilgrimage journey home? We can be reasonably sure that we will, in our own particular context, be presented with various versions of the question “Why don’t you act upon your green light?”

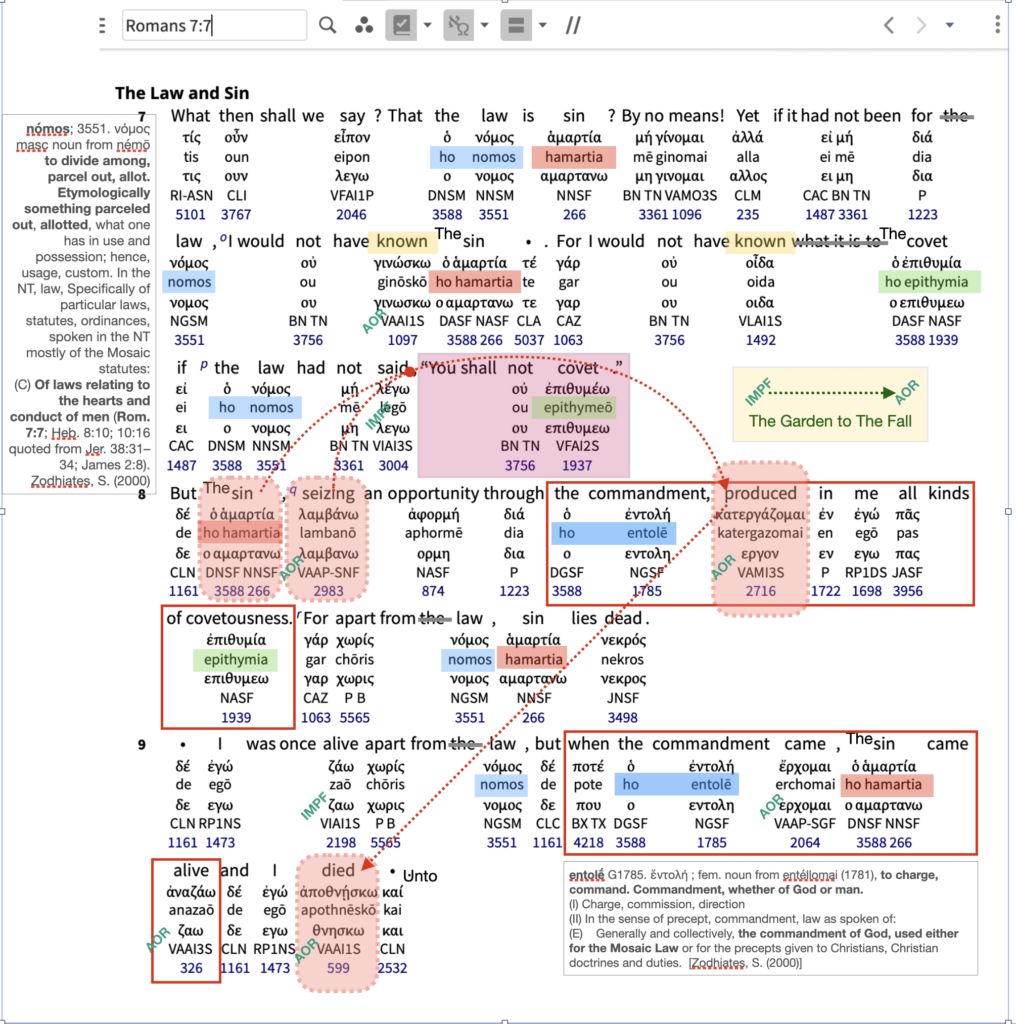

Deep Dive on Coveting in Romans 7:7-9 (ESV)

- Boundary words: nomos (5x) and entole (2x)

- Passion / Lust: epithymeo (3x)

- Sin: harmatia (5x)

- The recreation of The Fall evidenced in the two primary verb/participle tenses (aka “aspect”), contrasting the “IMPERFECT,” continuing action in the past to the present, and “AORIST,” a one-moment in time event with its enduring consequences (can also reference a whole action).

- The distinction between articulated nouns (with a “the) and anarthrous nouns (no “the”) is the latter tends to represent a condition of, a category of, whereas the former a specific instantiation.

The Sermon on the Mount and Coveting

The extended oration by Jesus recorded for us in Matt Ch 5-7 is known colloquially as “The Sermon on the Mount.” It is a widely known and beloved passage, that is frequently mis-taught. For our purposes here, we will consider the undergirding them of “coveting” as being one key of opening up the passage.

The Mosaic Law as it had been understood and taught in the days of the NT (and largely also in the OT), even as part of the more than 600 recognized OT commands within the Torah (the first five books of the Bible, known also as the Books of Moses) that it was deed based. There is a dictum in U.S. law known as ‘you can’t go to jail for what you’re thinking,’ meaning unless one actually does something–physical action or speech–then “The Law” has no means to reach within your head to deem you a lawbreaker.

In a similar fashion the OT Law(s) could be understood to pertain to ‘crossing some line’ from a harbored thought / passion into a physical act (including speech). So the heart, under such reasoning, with its passions, was not a lawbreaker so long as “the mind” or whatever we might attribute that which inhibits the passions within from being expressed in spacetime without, is securely buttoned down, and concealing the real inner condition.

This never should have made sense, but such is how The Religion Industry (TRI) tends to orient itself, and those seeking self-justification and self-redemption are inclined.

But the Sermon on the Mount exposes the previous error of such outer vs. inner distinction. Hence, the Lord begins the Sermon: “blessed are the poor…those who mourn…the meek…those who hunger and thirst for righteousness…” He is addressing those who at a fundamental level of their innermost being know, know deeply, that the externals and externalities of what had devolved into TRI at the time of the NT had not and could not cure the fallen heart, and consequent alienation from God. The underlying passion? It was “coveting,” longing for that which one did not have, was beyond a boundary of God, and toward which one’s passions where aligned and thoughts focused.