This week we will continue in Calvin’s Ch 5 of his Little Book (corresponding to his Institutes, Book 3, Ch 10), Sec.s 3 and 4. The theme of this important chapter is how to use / live in this present world, while we anticipate heaven (Ch 4), and while we struggle with self-denial (Ch 2), and in particular self-denial in the context of God’s use of a cross that we each bear (Ch 3).

Ch 5: How the Present Life and Its Comforts Should Be Used

Calvin re-introduces in Ch 5 the idea of “rule” for guiding one’s life, an idea that began the Little Book in the very first pages of Ch 1, and regarding which I created a series of charts, here:

The word “rule” can be troublesome as it could suggest some form of restatement of the OT Law. But that is not Calvin’s idea, nor is it the teaching of the NT. So, perhaps, a better term would “map,” in the metaphorical sense of the word, or even a “compass,” or better yet, both.

An important related idea that we covered in detail in Week #18 here is the idea of our being as a Pilgrim and, accordingly, journeying on a Pilgrimage. I created a special topic on this idea, here.

Calvin’s Heading for Ch 5, Sec.s 3-4

3. Excessive austerity, therefore, to be avoided.

So also must the wantonness of the flesh.

1. The creatures invite us to know, love, and honour the Creator.

2. This not done by the wicked, who only abuse these temporal mercies.4. All earthly blessings to be despised in comparison of the heavenly life.

Calvin, J., & Beveridge, H. (1845). Institutes of the Christian Religion (Vol. 2, p. 293). Edinburgh: The Calvin Translation Society.

Aspiration after this life destroyed by an excessive love of created objects.

First, Intemperance.

Verses Cited by Calvin in Ch 5, Sec.s 3-4

In the pdf below are the two Bible texts Calvin cites:

Deep Dive of Verses Cited

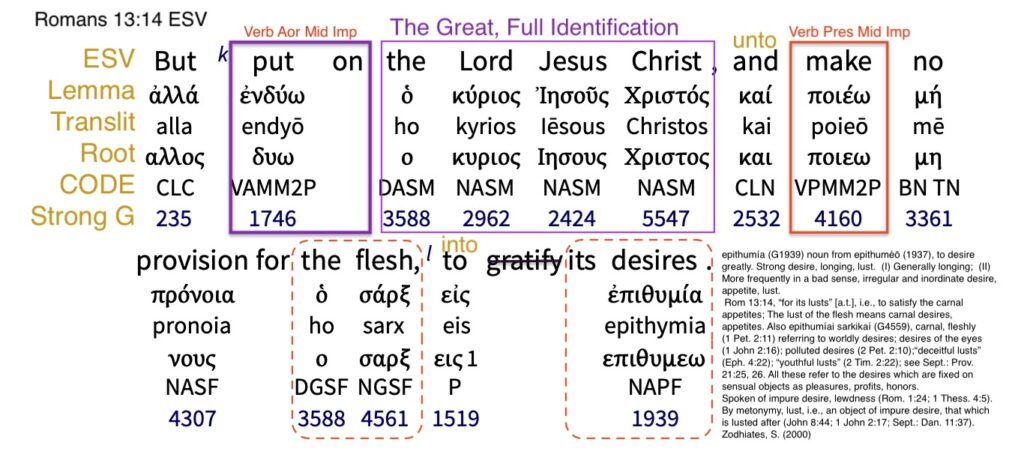

Below are highlighted interlinear forms of the above two important texts. The first one, from Romans 13, played an important role in Luther’s conversion (and, no doubt, many others before and since).

Romans 13:14

The superscript letters shown above, “k” and “l” are citations of parallel verses, namely:

- k: Gal. 3:27; Job 29:14; Ps. 132:9; Luke 24:49; Eph. 4:24; Col. 3:10

- l: Gal. 5:16; 1 Pet. 2:11

As highlighted above, there are two imperative verbs, both in the middle “voice” (meaning one is active in doing such to oneself), the first in the Aorist tense (generally designating whole / entire action, even to being a one-time framing event, such as entering a marriage covenant) and the second in the present tense. The Koine word kai is commonly translated “and,” as in the ESV, but is better in most cases and here (my judgment) conveying the idea of “unto.” This distinction between “and” and “unto” is the first suggests a two-step idea of independent actions, the latter, which is the case here, the second action derives from the first, and only so, especially so because the important tense shift (from aorist in the first verb to present in the second).

The word “provision” is made up of two parts: pro and nous, where nous can be understood as the mind, or ‘thought box,’ and the prefix pro as toward, or before. It conveys an important, beautiful concept: the “make no” is not asserting that there should, in a rightfully aligned Christian (having “put on”) thought that arise from and of the flesh. Rather it is the command to not orient one’s life, environment, thinking, plans, values whereby the fulfillment of the flesh’s lusts, including lusts of the eye (pride) is one’s frame / ‘map’ / ‘compass heading.’ So this text says, in the context of the world’s ‘compass heading’ of “if it feels good…it is good” and “if it feels good…do it”….God’s word says exactly the opposite. The flesh has value, in certain specific ways and contexts actually as given by our Creation, but only as a ‘passenger;’ the flesh makes the worst imaginable pilot.

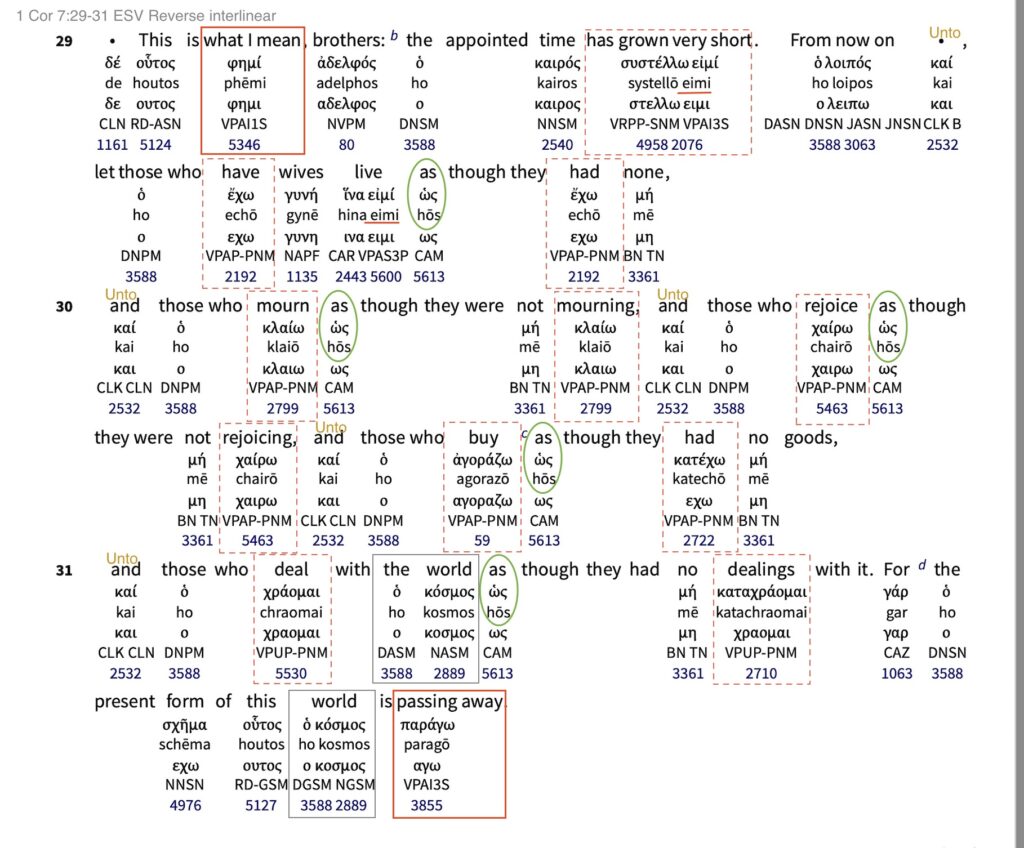

1 Cor 7:29-31

This is a remarkable passage both to its message and Koine. There are four verbs, two of “being” (eimi), highlighted by a red underline, and two present active indicative (statements of present fact), highlighted by red boxes. However, in addition there are 11 (!) participles, all also in the present tense except the first one which is a “perfect” (meaning that it began in some time in the past and continues to the present). Participles are verbs that are used to bring ‘life’ (describe in the sense of movement, action) other words in a sentence. If verbs are bight lights highlighting where and what is happening, participles are like little or not so little blinking lights suggesting that other words have an action element to them. So we might say in English “The running boy went home.” “Running” is the participle form of “to run” and of course describes the “boy,” conveying the idea that there is something more going on than just a boy going home, or even if the sentence replaced “went” with “ran,” as given with the participle it gives us a different, motion oriented picture of the scene.

Further in the above text are some other unusual aspects. As highlighted there are five matched ‘pairs’ of the words “kai” and “hos,” meaning “unto” (as described above in the Romans 13:14 text) and “as though” as translated in the above ESV. These five pairs, together with their accompanying participles, unveil five life-scenes: our unions of marriage (wives), the sorrowful experiences we all have (mourn, though not necessarily related to “wives,” LOL), the joyful experiences of life (rejoicing), the stuff of life (goods), all the many intertwined relationships of life (dealings). Each of these five can be thought of restraining force fields (a deeper subject than I can deal with here). And each of which because (1) time is short, and (2) this world (kosmos) is passing away, should not have a ‘hold’ on our innermost being (eimi, the twice used Koine verb of being).

Two other important words should be noted. The word translated “time” is not the Koine word “chronos,” which means clock time (as in chronometer), but the word “chairos,” which can be better expressed as “era” or “time period” or even “age.” Chairos is the idea that historians use when they characterize periods of historical time, as “medieval” or “the renaissance.” The text above does not give us a context for how long such chairos is, or was to be in the mind of the Corinthians receiving the letter from Paul. Rather it can be grasped as meaning that this period of time, which we know now as at least 2000 years of what is termed “the church age,” is that which connects the end of the OT Mosaic Law and fixed Temple in Jerusalem and all its attendant ceremonials and observances to the end times of the Tribulation, Rapture, Millennium, Great White Throne Judgment, and the New Heavens and New Earth, which will occur in an order and time yet to be known for certain. So, the teaching of this passage is that we are to live, as were the Corinthians, unfettered by our hearts being bound tight to the circumstances of spacetime. The passage does not teach against marriage, as is clear by other texts in this very same Epistle. Nor does it teach ascetic isolation from the world around us, again as made clear by other NT texts and contexts. Rather, our life is not “here”…we are passing through physically, emotionally, and spiritually.

The final word of note is the that which is translated “world,” namely “kosmos.” Kosmos has as its root meaning the idea of an ordered system, and in so ordered with a beauty even harmony and melody, like an orchestrated musical performance. The kosmos that surrounds seeks more than our good behavior as citizens and visitors; it also wants our obeisance. Such lure within the kosmos is the subject of other writing I am doing on The Religious Industry (TRI) and The Political Industry (TPI), two overlapping, even warring and cooperating at the same time, force fields. Such fields only ‘work’ on objects tuned to them, as a magnet to a magnetic field. This above passage is about being ‘unmagnetized’ such that such field has no restraining effect upon us.

What about marriage and wives? Both are clearly taught as a good thing in both the OT and NT, and held in high regard and to a high standard (as in God saying “I hate divorce”). Well, there is marriage, and there is marriage. Certain idealizations of marriage are as though it is the sole meaning of life. Such typically begin with extravagant arrangements for the marriage ceremony itself, compounded by glorious talk like “soulmates” and “forever love” and other terms conveying the belief that the marriage itself is the centralizing feature of life in spacetime. Then there are other, also genuine marriages, that are, me might say, are “down to earth,” just as the those first ones become in a few weeks or days after all that glorious talk fades like applause after a performance. Marriage, like work careers, like buying some very cool object (a motorbike!), are never to be a meaning of life event or experience. Like other features of life, joy of work / accomplishment, the experience of multiple sensations of beauty, so is marriage as it can be, should be. But it is not “life” nor should it be, as the great grip on our spacetime being. This is especially important in the context of death. God’s ideal for marriage is until death creates the separation. Unless by some unique circumstance, such death will not be simultaneous for both the husband and wife, so one will be taken and the other one left (as the song goes). The sorrow of loss is understandably real and deep, but ought not to be an exterminating factor as to the life of the one that remains. The one left behind may be disoriented, even lost for time; but life is not “over” because marriage was not the sole reality of life itself. There is work yet to do, and even joys to experience, for the one that awaits his, or her, ultimate regeneration to God’s heart. And in the meanwhile, the one who has gone ahead is not riding his motorbike through the heavens, or playing some banjo, as though our next life is merely a longer version of our present one with better stuff. Think of the contrast between a womb baby, just an inch or so separated from his or her soon-to-be physical life, and happy to stay were it is. But at a time not of its choosing, mom’s body says ‘out you go’ and the parents say ‘here you come’ to a continuation of your “womb life,” but in a very different form than you, being that very baby back at your own birth, could have ever imagined while in your mother’s womb. And, so, it will be in our ‘ejection’ from spacetime into God’s eternal Presence. (And, yes, I do hope there is sometime motorbike-like, but it won’t be the ‘meaning’ of eternity, just as it was not in spacetime; as to banjos…it’d be ok if they stayed here).

Key of Recognition that We are Pilgrims on Pilgrimage

As Calvin develops the key themes of Ch 5, he stresses the root concept of disengagement from the present world, but in a particular way. Our disengagement is not to be of extreme asceticism, which actually becomes a source of pride much as anorexia can become. Rather, we see ourselves as God does, belonging to a true home that is not of this world, but that ultimate, eternal world, is a “not yet” for us in the here and now. And, so, we journey on.

We need certain things, but only those, from and of the world on such journey. And the world needs something from us, even if only the testimony / proclamation of the Truth of God, the Source of His Word for it to be mocked and rejected. Such is not our delight or hope, but God has long shown us, from the time of Noah’s testimony, that it was and is His Intention to proclaim His Word even to those who will not believe.

And, then, there is that delight of encountering fellow travelers, as did Christian in Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, some moving a little faster and in greater peace and faith than us, some a little less so. We take comfort and learn from the first, and give it, as we can, to the latter. And along the way we make known as we have opportunity the Call to that Celestial City up ahead (using Bunyan’s terms for Christian’s ultimate destination).

I have collected in a Special Topic the basic points of Pilgrim, Pilgrimage, here:

Key of Gratitude

Calvin’s Sec. 5.3 begins, as his custom, with the theme (topic) sentence of the Section, and closes it as well. In both places he emphasizes the role of “Gratitude” in aid the balance of the mature Christian Life, keeping it from sliding off on the one hand to self-exalting asceticism as a pagan Stoic might well do or, on the other hand, to licentious (antinomian) living that gives full latitude to the impulses one’s flesh.

How to keep that middle ground. He earlier in Ch 5 made it clear, as does the NT, that there exists a middle ground. Knowing this, deeply, personally, is an important first step. (It should be noted that such middle ground is not the lukewarmness of the Laodicean error in Revelation 3:14ff; such lukewarmness was in regard to its attention to and claims of personal prosperity, being “rich” in material matters, and proud of it as though it were life’s primary accomplishment).

But then comes the details, the mechanics of so keeping on the purposeful middle ground. The key in Ch 5.3 is given as gratitude:

First one restraint is imposed when we hold that the object of creating all things was to teach us to know their author, and feel grateful for his indulgence. Where is the gratitude, if you so gorge or stupify yourself with feasting and wine as to be unfit for offices of piety, or the duties of your calling? Where the recognition of God, if the flesh, boiling forth [D&P “boiling over”] in lust through excessive indulgence, infects the mind with its impurity [D&P “corruption”], so as to lose the discernment of honour and rectitude[D&P “right”]?

Calvin, Beveridge translation. Ch 5.3, p. 117 D&P

Gratitude and the Recognition of the God the Giver

How does gratitude arise? It can be ‘invented’ by some mantra. But genuine gratitude stems from recognizing the Source of all Good, the Benevolent One. God has not only done the great thing, of redemption / propitiation / regeneration to eternal life. He has also overseen every detail of our ongoing life as the most loving Father imaginable. So every truly “good thing” we have, experience, or even know about, is given by God for our benefit, including our joy. However, there are bounds and context of our experiencing the specifics of each such “good thing” from God.

Fitness for Office, Piety, and Duties of One’s Calling

In the above quoted passage, Calvin notes one test for staying on that middle ground is examining how one’s experience of God’s “good thing” aligns with one’s “fitness” for one’s office (God-given responsibilities), for one’s calling (proper, excelling use of God’s gifts), and even one’s personal piety (devotion to God).

Discernment of the Honorable and Right

Another test given by Calvin above is that of discerning whether any particular course of action, or use or, or desire for, a “good thing” from God is intrinsically honorable or right. One of the sad consequences of a life of licentiousness is losing true discernment, whereby one loses even the ability to judge what is honorable as someone might experience the loss of the human senses, such as sound, or sight. Upon a further descent into such error, there can even be a total inversion such that what ‘seems good’ is, in God’s Sight, evil, and vice versa. But so it would appear in such a condition, life in an upside and backwards world. The alternative is to have something like a compass and map, that uses the compass to point to that which is “right” (correct in God’s Eye) and so map out one’s steps to a place that is “honorable”

The Danger of Devotion to Senses

We are each equipped to one degree or another with powerful tools of sensation. From modern biology we know that such sensations cause electro-chemical reactions in our brain along myriad dendrites each interconnected with on the order of thousand other dendrites across small gaps (synapses) that exchange signals by means of neurotransmitters, which in tern activate others neurotransmitters and so on. As we emerge into adulthood and continue until our death various synapses get strengthened–“what fires together, wires together”–creating powerful effects from the particular incoming stimuli (neurotransmitters).

Regardless of how little or much is known about all such biology, we all know this: repeated positive responses to thoughts, or actions, that give brain-pleasure ‘want’ to get repeated, and vice versa. This itself is not evil, again within the middle ground of God’s Call on us. But a life devoted to chasing sensations that boost by whatever means to whatever end the ‘feel good’ interconnections of our mind-body is a life on the way to dissipation and even utter ruin.

Calvin puts it this way: “For many people devote their senses to pleasures so much that their minds are buried in them.” (D&P, p. 118. Calvin’s Latin is:

nam totos suos [for whole his / one’s] sensus [perceive, experience, feel]

multi [all, every] sic [thus, so] deliciis [activity associated with luxuries, toys, ornaments, decorations, even erotica]

addicunt [doom, enslave, confiscate as one’s senses can become imprisoned by sensation],

ut mens [mind] obruta [cover up, bury, ruin, crush]

iaceat [in ruins, prostrate–driven down, even to be dead]:

Calvin’s Latin original text, D&P p. 118

That above sentence captures the ruin of many a young (and old) man (and woman), as the song goes (“The House of the Rising Sun,” but most definitely not “of the Risen Son”).

Devotion to Heavenly Immortality

Calvin begins Ch 5.4 (D&P p. 119) with this important observation:

5.4. There is no surer or quicker way of accomplishing this than by despising the present life and aspiring to celestial immortality.

Calvin / Beveridge, Ibid.

However, as noted previously, and frequently, such “despising” it not with regard to God’s gifts and calling, including the enjoyments thereof. “Despising” in Calvin’s intention is more akin to the experiences of Pilgrims Christian and Faithful when on their Pilgrimage they necessarily had to pass through the town of Vanity Fair, a place with all day every day deals only in vanities.

Calvin ends this 5.4 section with the following:

Therefore, while the liberty of the Christian in external matters is not to be tied down to a strict rule, it is, however, subject to this law—he must indulge as little as possible; on the other hand, it must be his constant aim, not only to curb luxury, but to cut off all show of superfluous abundance, and carefully beware of converting a help into an hinderance.

Ibid.

The final phrase is particularly noteworthy, as to the always-caution of having a “help” be transformed into a “hinderance.” Missing this has also been the the ruin of many.

Jonathan Edwards and His 70 Resolutions

Jonathan Edwards (1709 – 1754) was one of the ‘giants’ of Christian leadership and theology in the early years of what later became the United States. As a young man he began writing to himself, for himself, “resolutions.” Each was to be reviewed weekly as a reminder to himself of his compass heading, and map, given God’s gifts to him and calling of him. In the course of a few years such resolutions expanded to 70 in number.

Although they were written to be personal, these were found and published and have been available now for more than 250 years. One useful version of these is a grouping by categories. (Edwards’s original was simply in sequential order as they occurred to him). A pdf of such organization of all 70 is given in the pdf below:

Boundaries and Obstacles

Calvin began Ch 5 using the term “rule” in the sense of a guideline for life in the here and now. I think the idea is not “rule” in the sense of “law” or “rules of men,” but more, in terms that I think better fit our language today, a “map” with a “compass” (alas, now GPS).

Just as safety barriers along interstate highways, and bannisters and other railings, serve our safe physical travels and movements, and fences and boundaries mark out for us the direction of the road ahead, we can benefit, and need, parallel versions of such in our spiritual journey / pilgrimage home. Again referencing Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, the Pilgrim Christian found himself in deep trouble when he saw, what appeared to be or was told it would be, an easier shortcut. Those departures did not turn out well.

Boundaries are particularly important when we encounter “obstacles” on God’s road of travel for us. These can lead to resentment (that they exist, “the thorns” of life emanating from Adam’s judgment extending down to us too), stoppages, diversions, and even retreats. In Calvin’s Chapters 2 and 3 on the subject of self-denial he led us through the virtues of these various forms of difficulties of life.

In another Special Topic, I have collected certain thoughts on boundaries and obstacles, here:

The Bible’s Caution Regarding Following the Rules of Men

In the Epistle to the Colossians, there is a wise reminder as to the danger, and error, of following the rules of men (including Edwards, as above).

6 Therefore, as you received Christ Jesus the Lord, so walk in him, 7 rooted and built up in him and established in the faith, just as you were taught, abounding in thanksgiving. 8 See to it that no one takes you captive by philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the world, and not according to Christ. 9 For in him the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily, 10 and you have been filled in him, who is the head of all rule and authority. 11 In him also you were circumcised with a circumcision made without hands, by putting off the body of the flesh, by the circumcision of Christ, 12 having been buried with him in baptism, in which you were also raised with him through faith in the powerful working of God, who raised him from the dead. 13 And you, who were dead in your trespasses and the uncircumcision of your flesh, God made alive together with him, having forgiven us all our trespasses, 14 by canceling the record of debt that stood against us with its legal demands. This he set aside, nailing it to the cross. 15 He disarmed the rulers and authorities and put them to open shame, by triumphing over them in him.

Col. 2:6-15, ESV