Context

John Calvin (1509 – 1563) was a key contributor to the Reformation. His most famed legacy is his systematic theology written over a period of some 25 years in four distinct editions, finally comprising 80 chapters divided into four “books.” It was entitled Institutes of the Christian Religion. In today’s context, a more appropriate titling would be Systematic Theology of the Scriptures (or of the Christian Faith). But Institutes it remains.

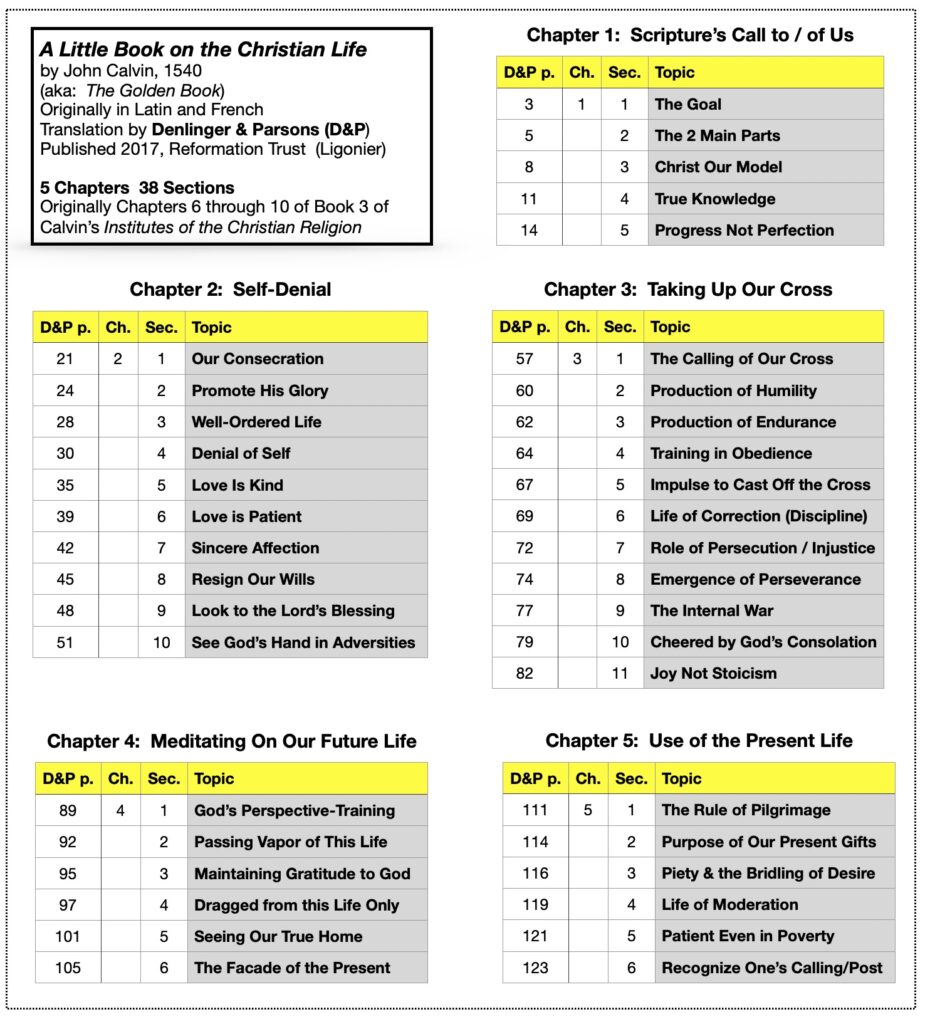

Embedded in the Institutes are five practical chapters on the Christian life of a mature believer. In the final edition of the Institutes, these where located in Book 3, Chapters 6 through 10. Dating from approximately 1540 these five chapters were separately published as a Little Book under various titles.

The primary version we will consider here is the 2017 publication by Reformation Trust entitled A Little Book on the Christian Life, or simply, here, Little Book. This was a new translation of the Calvin’s original Latin writing by Denlinger and Parsons (D&P as a shorthand). It is widely available in multiple formats: leather bound, paperback, and kindle. The pagination reference here will correspond to the print editions. An alternative translation by Henry Beveridge (Beveridge, 1845), is in the public domain and available from multiple online sites. (Other translations, as well as Calvin’s original Latin and French editions, will be referenced for specific words translated by D&P).

Public domain sources for the Beveridge translation are here and here and in various formats here.

Why This Book?

Calvin himself is worth serious study, both because of his wide influence at a critical period of the church and for the scholarly content of his writing and thought. However, that is not our purpose here.

Calvin the Archaeologist

Our interest is the Bible itself, not Calvin himself. Then why Calvin at all?

The primary method by which we study the Scriptures is to dig right into any given Book of the Bible and go through it, verse by verse, as deeply and carefully as we are able. Morris Proctor, well-known for his teaching of the Logos Software, has a useful three-step mnemonic: (1) READ the Word, (2) KNEAD the Word, and (3) HEED the Word. This direct approach is helped by commentaries, group study, teacher-led studies, drilling down on individual words using, for example Strong’s numbers (discussed elsewhere on this site) for those with limited original language skills, or diving directly into the underlying Hebrew and Greek manuscripts (mss).

A limitation of such primary is the difficulty of integrating, or cohering, what is grasped in verse-by-verse study with all the remaining relevant Scripture. And with certain Books, such as Romans and Hebrews, attempting to do such cohering across all Scripture for every key verse would create one’s own systematic theology and be more than a lifetime’s project. So, an alternative, supplemental study method is to focus from the onset on a certain theme (topic) and work across all of Scripture wherever it takes us.

Here’s where Calvin can help us. He, though finite and imperfect, was a gifted and lifelong scholar who, in the company of some outstanding companions (Farrel, Beze, and Knox, for instance) dedicated himself to both verse-by-verse and synoptic study of the entire Bible. In particular, Calvin’s Institutes, as a systematic theology, is by its name a coherence of many essential doctrines out of all the Scriptures, within the limitations of time and space and the insight of one mortal being.

So it is helpful to think of Calvin as a highly skilled, experience archaeologist–not of stuff buried beneath the earth, but of the truth and meaning containing within the Scriptures. But such value has to derive from a structure or we fall into the danger of simply being ‘Calvinists,’ meaning, as it usually is pejoratively applied, someone who blindly follows what Calvin taught. The distinction between being a strict ‘Calvinist’ (dogmatic follower) and leveraging his gifts and work to both accelerate and deepen our own understanding of the Scriptures themselves can be made clear by using a parallel to physical archaeology.

Two Rules, Plus One, of Physical Archaeology

Like Morris Proctor’s mnemonic cited above, there is a two rule dogma of physical archaeology: (1) First ‘The Dig,’ and (2) then ‘The Tale.’ The simple idea is this: archaeologists must constantly remind themselves in their own primary investigations as well as reading the reports of others that one must start with the findings of ‘The Dig.’ It is all too easy, even normal, to have ‘The Tale’ in mind, because we are sentient beings who inevitably orient life by what we know or think we know, and such afore ‘knowledge’ corrupts in some way(s) ‘The Dig.’ There is even a psychological term for an everyday version of this: “confirmation bias,” meaning one tends ‘to see’ (‘The Dig’) what one already “knows” to be true (‘The Tale’). There is an artistic version of the same phenomena: paint what you see, not what you know. This guidance is especially relevant to portraits. When one paints noses and other face parts by what we think we know about how they are positioned and denoted the result is very unlike the face we are drawing. First ‘The Dig,’ carefully study the subject, then portray ‘The Tale,’ express the person in some art medium.

In physical archaeology there is a ‘Plus One’ rule relevant to our discussion here. It is what comes before even ‘The Dig:’ it is known by the term “Provenance,” archaeological language that (broadly) means to know the context in which the dig occurs. When archaeological objects have been collected absent such careful provenance they have far less scientific value: every object ‘networks’ in some important way with its neighbors and surroundings. Each finding, each one, gives ‘life’ to every other finding. No proper, scientific archaeological dig is done with bulldozers or–horrific thought–dynamited expanses of an interesting site. One wants to find the belongingness of each artifact as well as the the artifact itself.

Back to Calvin

When reading the Little Book we are primarily given Calvin’s view of ‘The Tale,’ namely the findings and coherence (‘network’) of the Scriptures on the subject matter on which he is writing. As we will see his topics are: (1) a Model for a mature Christian Life, (2) the need for Self-Denial, and (3) the need for Viewing the Present and Future Life. But Calvin, and others who have studied the Little Book additionally provide us their work of ‘The Dig’ that preceded summary discussion of those three topics (‘The Tale’). It is for us, then, to examine the artifacts that Calvin found and used, namely the citations of the Scriptures themselves. So, we want to use Calvin’s archaeological methods, and eye of observation, to see what he found, and his wisdom in putting it all together, to see if we grasp the big, coherent picture and in fact find it compellingly accurate.

What about the Provenance? There’s another mnemonic on Bible study: (1) Christ is King, and (2) context is ‘Queen.’ In a very parallel way to physical archaeology, a mere pile of verse citations can be of very little value or even a distortion of truth. The Enemy is really good at doing this; recall Christ’s Temptation after His 40 day fast.

For a faithful ‘dig,’ the application of the principle of Provenance has two parts. First we need a faithful, wise digger. Again there are a legion of examples of writers and preachers who had a particular, even peculiar, even evil, motive in digging out some pile of verses out of the 30,000+ verses of the Bible. Further, even if the the digger is both faithful and wise as a digger, cohering the findings into ‘The Tale’ requires a distinct, important, and unique gift.

No human is infallible at all this, even those faithfully committed to the infallible Authorship fo the Bible by God Himself. But, we know God has gifted some with particular abilities of doing such investigative work and reporting. And He has gifted all of us with some degree of discernment to bear witness to the truth of what we are reading or hearing (remember the Bereans and see 1 Thes 5:18-22).

Study Outline of Calvin’s Little Book

A map of the Denlinger & Parson’s (D&P) translation is below. The D&P translation does not include the useful Section number identification; the reader is encouraged to write them in the book for ready reference. It would be useful to print out the below map of Calvin’s Little Book. The chart below can be used as a bookmark: print it out, cut the dotted line perimeter, and fold it lengthwise, and it will fit in the small book formate of Calvin’s Little Book. All the topic descriptions are my own brief summary of the respective Section.

As noted, these five chapters are comprised of 38 Sections, divided as Calvin intended them. Such division makes the book useful for reading one Section a day, along with the examination of the Scripture Calvin cites, completing the book in five or so weeks, an exercise that could be usefully repeated perhaps every four or six months.

Links to Each Week’s Deep-Dive Study

At the links below are the weekly ‘deeper-dive’ studies and additional resources prompted and organized by the respective Sections Calvin’s Little Book. The Section numbers referenced below were Calvin’s and included in the Beveridge translation (1845) to which I make frequent reference. The page numbers are from the Denlinger & Parson’s (D&P) translation.

The resources provided at the respective links are given below are intended as aids to thinking about Calvin’s dig and tale.

Chapter 1: Scripture’s Call to Christian Living

Week #1: Chapter 1, Sec. 1-2, pp. 3-8 (D&P)

Week #2: Chapter 1, Sec. 3, pp. 8-9

Week #3: Chapter 1, Sec. 3-5, pp. 10-17

Chapter 2: Self-Denial in the Christian Life

Week #4: Chapter 2, Sec. 1-2, pp. 21-27

Week #5: Chapter 2, Sec. 3-4, pp. 28-35

Week #6: Chapter 2, Sec. 5-6, pp. 35-42

Week #7: Chapter 2, Sec. 7-8, pp. 42-48

Week #8: Chapter 2, Sec. 9-10, pp. 48-54

Chapter 3: Our Cross is Part of Self-Denial

Week #9: Chapter 3, Sec. 1-2. pp. 57-62

Week #10: Chapter 3, Sec. 2-4, pp. 62-66

Week #11: Chapter 3, Sec. 5-6, pp. 67-71

Week #12, Chapter 3, Sec. 7-9, pp. 72-79

Week #13, Chapter 3, Sec. 9-11, pp. 77-85

Chapter 4: Meditation on Our Future Life

Week #14, Chapter 4, Sec. 1-3, pp. 89-97

Week #15, Review of “Little Book,” focus on Sanctification

Week #16: Chapter 4, Sec. 4, pp. 97-11

Week #17: Chapter 4, Sec. 5-6, pp. 101-108

Chapter 5: How the Present Life and Its Comforts Should Be Used

Week #18: Chapter 5, Sec. 1-2, pp. 109-116

Week #19: Chapter 5, Sec. 3-4, pp. 116-121

Week #20: Chapter 5, Sec. 5-6, pp. 121-126. (The final Ch and Sec)

Special Topics from Calvin’s Little Book

At the links below are special topics that arise from the study of various chapters and sections in Calvin’s Little Book:

The World as Evil and Vanity Fair

Collected Charts Used in Various Week’s Studies

A link to just the charts used in our studies is here: